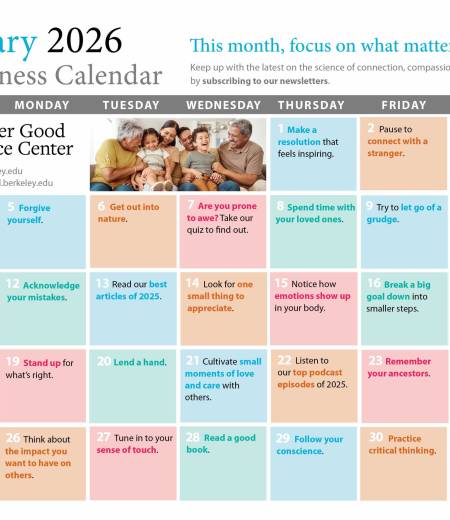

When we meet sisters Dorriene and Jo Diggs for the first time in the premiere episode of Queer Eye’s tenth and final season, they’re nearly five years into a life chapter that neither saw coming.

Dorriene and Jo Diggs in Queer Eye.

Dorriene and Jo Diggs in Queer Eye.

Dorriene’s partner, Diane, passed away in 2020. They’d been together for 40 years, and Dorriene was devastated. She couldn’t bear to stay in the house where Diane had died. She called her sister and asked, “Can you come get me?” The two retirees now live in Jo’s house with Jo’s granddaughter Breelyn and great granddaughter Soulann (a.k.a. baby Soso).

These days, Dorriene spends most of her time alone in her bedroom. When she emerges to interact with Jo and the rest of the family, the house fills with bickering and what Breelyn describes as “bad energy.” While Jo and Dorriene are physically closer than ever, they’re struggling to bridge the emotional distance. They recognize the impact they’re having on the household, but they don’t know what to do.

That’s where Queer Eye’s Fab Five come in. They’ve arrived in Washington D.C., ready to help Jo and Dorriene find their way back to each other or, at the very least, to create a more peaceful environment for baby Soso. Certainly, over the course of ten seasons, the show hasn’t always gotten it right on set or on screen. But in this episode, as the Queer Eye team works to help Jo and Dorriene reconnect, they demonstrate how transformative (and fun!) bridging practices can be when they’re implemented skillfully. Here are four research-backed best practices for bridging differences, all beautifully modeled in this episode.

1. Focus on common goals and keep trying

Jo and Dorriene disagree on a stunning array of topics–what to watch on TV, how to clean, and what kind of childhood they had growing up in a family with 18 kids. Queer Eye’s resident food and wine expert Antoni Porowski notices one thing the sisters can agree on: their mom’s pineapple upside down cake was delicious.

This rare moment of consensus sparks a fruitful idea (pun intended). Antoni surprises Jo and Dorriene with an outing to a restaurant where, in the kitchen, he has assembled all of the supplies one needs to bake a pineapple upside down cake. The sisters jump to it, explaining how much brown sugar to use (more than you think!) and whether to use milk or pineapple juice in the recipe (juice!).

The sisters work together seamlessly. There’s laughter. The jokes are gentler than the sharp barbs they exchanged in earlier scenes. Antoni notices the growing warmth between them and he casually floats a more meaningful question: When did you used to eat this cake growing up? Stories emerge. The conversation gets deeper.

In this scene, Antoni, Jo, and Dorriene show us the power of a common goal. Dorriene and Jo both wanted to make a pineapple upside down cake, and that common goal was enough to get them working together. As we explain in the Bridging Differences Playbook, a shared objective can help move us away from disagreements and toward collective action. We don’t need to agree on everything in order to make something happen. And actively engaging in making something happen can help warm us up to one another. It can also result in a delicious cake!

One of the other key aspects of the experience that Antoni facilitated is its repeatability. As social psychologists Linda Tropp and Trisha Dehrone note in Cultivating Contact: A Guide to Building Bridges and Meaningful Connections Between Groups, research shows it takes time and repeated interaction for members of different groups to build trust.

Antoni directly acknowledges that reality. With the sisters out of earshot, he tells the camera that he’s not trying to change a decades-old dynamic in one afternoon. If Jo and Dorriene keep cooking and baking together on a regular basis, their relationship will continue to shift. Before Antony’s time with Jo and Dorriene ends, the sisters decide what they’ll bake next–a quiche.

2. Give your perspective

Dorriene and Jo were born and raised in D.C. and they have a lot of family around. Jo is close with the family. Dorriene is not and hasn’t been for many years. Dorriene’s not up for something as simple as watching TV in the living room with Jo, Breelyn, and Soso, and she’s certainly not interested in attending larger family functions. Jo can see that Dorriene is lonely, and doesn’t understand why she won’t just leave the past in the past and come be part of the family again.

The Fab Five get it, though. They know it’s possible to grow up in the same house with someone and feel like your hearts are a million miles apart. For many of us queer folks, the feeling is all too familiar. We can share geography, skin color, faith, even the same parents and still not share a sense of belonging.

In an effort to build more understanding between the two sisters, Karamo Brown, the show’s culture expert, facilitates an experience that we at the GGSC call perspective-giving.

Karamo brings Dorriene and Jo to the D.C. History Center where they’re greeted by Ashley Bamfo, treasurer of the Rainbow History Project. As part of their mission to collect, preserve, and promote D.C.’s LGBTQ+ history, the Rainbow History Project maintains an archive of oral histories. Karamo reveals that he has brought Dorriene here to have her oral history recorded. He has brought Jo here to witness. He explains:

Dorriene, your story touched me because–to hear you say that you were in a relationship for 40 years–as younger queer people, the only reason I knew that I could find love and I could have somebody is because I see models like you. I want to make sure you have a chance to tell your story. I want us to document it because it’s important. As long as this country is around, they know Dorriene’s story.

While this episode’s primary focus is helping Jo and Dorriene build a stronger connection with one another, Karamo is also making it clear that he wants Dorriene to feel a sense of belonging to the queer community. Dorriene and her partner Diane belong to D.C. queer history. They are part of this long, storied tradition of love and resistance, and it’s important that this truth is preserved in the archives.

With all of this context set, Dorriene starts talking. We only see portions of what was surely a much longer experience, but even in excerpts, her stories do big work.

Dorriene tearfully opens up about “the things you had to do just to be loved.” How it felt to sneak around and keep secrets. How it felt to be treated poorly by their parents when she saw how much love and care her siblings got. She says:

I remember my mom looking at me with such hatred. Like I did something wrong, you know. That she was ashamed of me. That I wasn’t part of the family. That I wasn’t her daughter. That hurt. [...] That’s why when I left home at 14, I never looked back. And I moved in with a drag queen!

She recounts the day she met Diane in their apartment building’s laundry room and the day, less than three weeks later, when she moved in with her! (They lived in the same building. No U-Haul required.) She even talks about the time she married David, one of her gay male friends, to protect him from getting kicked out of the military.

Dorriene shares her perspective, and Jo listens. Boy, does she listen.…

3. Listen with empathy

Throughout the oral history interview, Karamo and Ashley model a bridging practice that we call listening with empathy. Karamo and Ashley ask thoughtful, open-ended questions, but never interrupt. They affirm Dorriene’s experiences and feelings. They let themselves be moved, expressing empathy.

In this artfully edited scene, we get to watch Jo learning from Karamo and Ashley’s example. Instead of lecturing or offering solutions, as we’ve watched her do in the past, Jo stays curious. She listens. She opens herself up to Dorriene’s pain. When she does eventually speak, she expresses empathy. She says, wiping tears from her cheeks, “It hurts. I’m not saying it to take from you. I’m hurting for you.”

Dorriene has a strong response to receiving empathetic listening. She softens towards Jo and she’s willing to engage in deeper perspective-giving. She even shares information about her childhood that she had never revealed to Jo before. Dorriene’s reaction to being listened to is a response that’s reflected in the research. Studies show that when we listen to someone with empathy, it increases trust between us and helps them feel less guarded. They’re more likely to want to take the risk of connecting with us across our differences when they feel that we’ve listened to them and understand them.

Everyone responds to different expressions of empathetic listening, but some combination of the following actions often helps people feel listened to:

- Be curious: Are you asking questions to encourage the other person to elaborate on his thoughts or feelings? Curiosity shows that you’re interested in what the person has to say and that you care.

- Be present: Are you actively engaged in the conversation, refraining from passing judgment, preventing interruptions, staying mentally focused, and avoiding the urge to give advice?

- Affirm feelings/intentions: How are you affirming the feelings or opinions of the speaker? Do your best to try to find what you are able to affirm, so it doesn’t come across as insincere.

- Express empathy: Why does the speaker feel or think the way they do? Think less about how you would feel or think in their situation, and more about them.

- Use engaged body language: Are you using your body language and gestures to convey active listening?

It’s the pairing of perspective-giving and empathetic listening that prepares Dorriene to make a big leap at the end of the episode.

4. Shift power imbalances

As even the most casual Queer Eye viewer knows, each episode ends with a big community celebration. Everyone gets to ooh and ahh over the makeover and the home renovations, but the real purpose is for the episode’s hero to be loved on and appreciated by their people. This episode’s final celebration certainly doesn’t disappoint. Karamo works with Jo’s granddaughter Breelyn to throw a family reunion at a gay bar, complete with a drag show.

When Karamo and Breelyn tell Jo and Dorriene what they’ve arranged, the sisters are delighted. Karamo is sure to clarify that they’ve only invited family members who affirm Dorriene’s humanity. He says, “The family members that love you and support you are there waiting for you.” We don’t see any of the pushback we might have expected from Dorriene. She’s surprised, but excited. At the bar, she and Jo seem to have a fantastic time with their given and chosen family.

In selecting this location and this form of entertainment, the show does something that researchers Linda Tropp and Trisha Dehrone characterize as a best practice for facilitating effective contact between groups. They shifted a power imbalance. In Tropp and Dehrone’s discussion of how organizations can design opportunities for contact between members of different groups, they write:

[W]e want to make sure that we envision and structure contact programs in ways that allow people from all groups to contribute as equal partners. [...] We can reinforce the equalizing nature of contact programs further by acknowledging and addressing ways in which broader societal inequalities might shape people’s participation in contact programs. [...] Rather than ignoring these differences, try to envision how you can address them directly as you consider what it will take for people from different groups to participate in your program.

It’s long been Jo’s dream to reunite Dorriene with their extended family, to bring her into the community that Jo treasures. It appears as though, with all of the progress they make over the course of the week, Dorriene might be ready to connect with more people. But it’s likely still a stretch for her. With an awareness of that reality, the Queer Eye team chooses a physical location and an activity that feel like home to Dorriene. She gets to regain some social power by being in that setting. By hosting the reunion at a gay bar and featuring drag performers, the crew addressed the impact that a broader social inequity had on Dorriene.

Dorriene and Jo Diggs

Dorriene and Jo Diggs

The Queer Eye team recognized the need to address this power imbalance because they understand that while the rift between Jo and Dorriene is personal, it’s also situated within a larger cultural context that includes systems of power.

One of the most noteworthy elements of the episode is the way the show invites the viewer to grow this understanding, as well. The episode is edited in such a way that interpersonal scenes are always connected to one another with references to the structural forces at play. Archival footage cut throughout the episode, paired with short, direct-to-camera interstitial commentary from the hosts, situate Jo and Dorriene’s personal stories within the contexts of D.C.’s civil rights movement, the gay liberation movement, and feminism.

By the time we get to the final party, the viewer has had an opportunity to repeatedly see and hear how Jo and Dorriene’s stories (and the differences that divided them) have both interpersonal and structural elements.

Healing can also happen in our connections to individuals and to movements. Being connected to histories and movements can help us feel less alone. It can connect us to resources that foster bridging, as well. As Don Martin notes in his book, Where Did Everybody Go?: Why We’re Lonely but Not Alone, the sites that nurtured movements of collective liberation–like gay bars and Black barber shops–can be powerful, effective locations for cultivating belonging more broadly. That’s not to say that every queer or Black space should be compelled to become a site for bridging work. Bridging is not everyone’s responsibility or calling. But for communities who are interested in connecting across differences, it’s nice to remember that these sites have a lot to offer, not least of which is FUN.

Practicing bridging differences can certainly make us more patient, curious, and courageous people. It can help us create a more loving and just world. The Diggs sisters and the Fab Five remind us that it can also bring more joy into our lives. As Dorriene says before going to the family reunion, “We had so much fun this week.”

Comments