Given the grinding wars and toxic political divisions that dominate the news, it might come as a surprise to hear that there are also a multitude of sustainably peaceful societies thriving across the globe today. These are communities that have managed to figure out how to live together in peace—internally within their borders, externally with neighbors, or both—for 50, 100, even several hundred years. This simple fact directly refutes the widely held and often self-fulfilling belief that humans are innately territorial and hardwired for war.

What does it take to live in peace? The Sustaining Peace Project is finding out.

What does it take to live in peace? The Sustaining Peace Project is finding out.

The international community has struggled with a similar attention-to-peace deficit disorder. In fact, the United Nations has been attempting for decades to pivot from crisis management to its primary mandate to “sustain international peace in all its dimensions.” Yet by its own account, “the key Charter task of sustaining peace remains critically under-recognized, under-prioritized, and under-resourced globally and within the United Nations.”

Science could play a crucial role in specifying the aspects of community life that contribute to sustaining peace. Unfortunately, our understanding of more pacific societies is limited by the fact that they are rarely studied. Humans mostly study the things we fear—cancer, depression, violence, and war—and so we have mostly studied peace in the context or aftermath of war. When peaceful places are studied, researchers (much like the U.N.) tend to focus primarily on negative peace, or the circumstances that keep violence at bay, to the neglect of positive peace, or the things that promote and sustain more just, harmonious, prosocial relations. As a result, we know much more about how to get out of war than we do about how to build thriving, peaceful communities.

In response to this gap in our understanding of how to sustain peace, an eclectic group of scholars started gathering together in 2014. We are psychologists, anthropologists, philosophers, astrophysicists, environmental scientists, political scientists, data scientists, and communications experts, who are interested in gaining a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of lasting peace. We also share an appreciation of the benefits of using methods from complexity science to better visualize and model the complex dynamics of such societies, and as a platform for communicating with one another across such different disciplines to develop a shared understanding of stable, peaceful societies and of peace systems.

Peace systems are clusters of neighboring societies that do not make war with each other, and anthropological and historical cases of such non-warring social systems exist across time and around the globe. None of the five Nordic nations, for instance, have met one another on the battlefield for over 200 years. Other examples of peace systems include 10 neighboring tribes of the Brazilian Upper Xingu River basin, the Swiss cantons that unified to form Switzerland in 1848, the Iroquois Confederation, and the E.U.

The mere existence of peace systems challenges the assumption that societies everywhere are prone to wage war with their neighbors—and what we have gleaned from studying these societies is promising.

Finding the seeds of peace

Our journey to date has been circuitous but fruitful. It began with a dive into the published science on peacefulness, which helped us to identify some of the more influential scholars in this area. We then surveyed this group to identify their sense of the most central components of achieving lasting peace (74 experts from 35 disciplines responded), and then invited the respondents to a day-long workshop to make sense of the findings. Next, our core team worked with this information to develop a basic conceptual model of sustaining peace.

The focus of our model is simple. It views the central dynamic responsible for the emergence of sustainably peaceful relations in communities as the thousands or millions of daily reciprocal interactions that happen between members of different groups in those communities, and the degree to which more positive interactions outweigh more negative. That’s it. The more positive reciprocity and the less negative reciprocity between members of different groups, the more sustainable the peace.

In other words, peace is not just an absence of violence and war, but also people and groups getting along prosocially with each other: the cooperation, sharing, and kindness that we see in everyday society. Sustaining peace happens through positive reciprocity: I show you a kindness and you do me a favor in return, multiplied throughout the social world a million times over.

Next, we started gathering together all the relevant science on positive or negative intergroup reciprocity. For example, studies on Mauritius, the most peaceful nation in Africa, have found intentionality in how members of different ethnic groups speak with one another in public. Mauritians of all stripes tend to be respectful and careful in their daily encounters with others. This even translates to differences in how journalists and editors report the news, and how teachers, politicians, and clergy take up their roles in society. These findings suggest that the citizens of this highly diverse nation do not take their peacefulness for granted—they recognize that it must be cultivated and protected.

We then organized these variables by three levels (individual, group, and society) and by their dominant effects (promoting peacefulness or preventing violence). Here are the elements we found promoted peace and nonviolence in individuals (the micro level):

| EVIDENCE ON PEACE-PROMOTING (INDIVIDUAL ELEMENTS) | EVIDENCE ON NONVIOLENCE (INDIVIDUAL ELEMENTS) |

|---|---|

|

|

Here are the factors that promote peace and nonviolence on the family and community (or “meso”) level:

| EVIDENCE ON PEACE-PROMOTING (COMMUNITY ELEMENTS) | EVIDENCE ON NONVIOLENCE (COMMUNITY ELEMENTS) |

|---|---|

|

|

And, finally, at the macro level of society and internationally, we found these qualities that promote positive intergroup interactions—and those that prevent or mitigate negative relations:

| EVIDENCE ON PEACE-PROMOTING (MACRO ELEMENTS) | EVIDENCE ON NONVIOLENCE (MACRO ELEMENTS) |

|---|---|

|

|

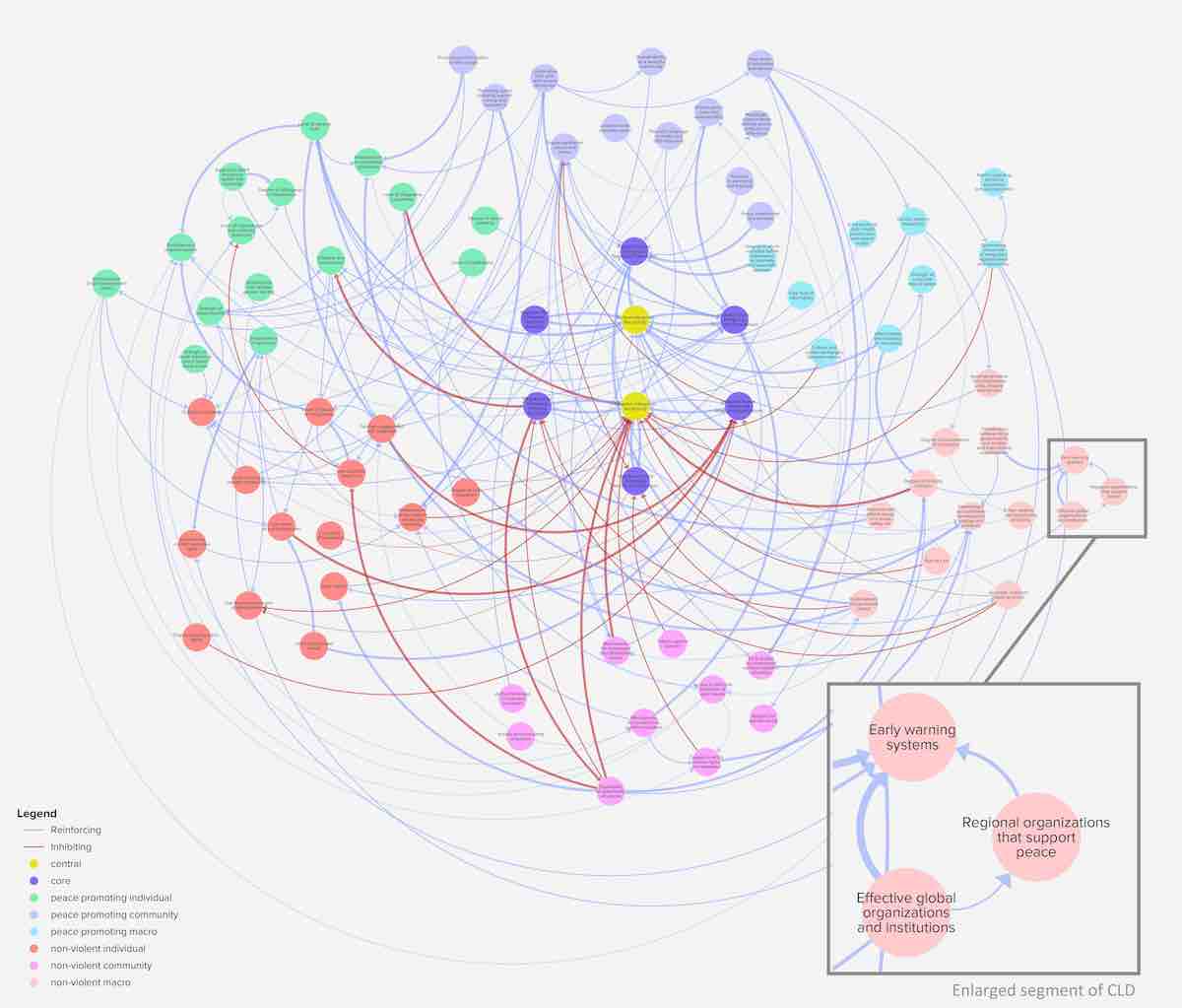

We then began to map the effects that each of these variables have on positive and negative group interactions, and on the other variables in the system. This is called causal-loop diagramming, and entails synthesizing the findings from hundreds of studies on dozens of variables to understand one simple dynamic: how they increase the chances that members of in-groups treat members of out-groups positively and inclusively rather than negatively and exclusively. This visualization gives us a coherent, birds-eye view of a larger system of peace dynamics.

At this point, our in-house astrophysicist, Larry Liebovitch, went rogue one long weekend and decided to mathematize this model (I believe with the aid of lots of caffeinated soda), developing an algorithm that captured its core dynamics. This allowed us to build a computer simulation that invites us (and you) to play with the different variables in the model to see how increasing or decreasing them might change patterns in this complex system.

Through this work, we’ve found that sustaining peace can be understood as a high ratio of positive intergroup reciprocity to negative intergroup reciprocity that is stable over time. In fact, this is exactly the type of interpersonal dynamic that researchers have found to lead to more thriving, stable marriages and families. This simple micro-dynamic of peacefulness has allowed us to begin to connect the dots between the multitude of variables investigated in thousands of studies across dozens of disciplines relevant to sustaining peace. This more basic and comprehensive approach to thinking about peace offers scholars, policymakers, and the public a sense of its complexity and simplicity, as well as (with the aid of the math model) insight into how particular policies and programs may result in intended, unintended, and even quite harmful consequences.

In parallel to building the math model, Doug Fry and Geneviève Souillac went back into the tomes of ethnographic studies that they had compiled over decades on peaceful societies and peace systems, and with their students coded for variables that they had found through previous research to be prominent in these societies. This allowed them to conduct a comparison study between 16 peace systems (such as the Nordic countries since 1815 and the Orang Asli of Malaysia) and 30 non-peace systems.

During this time, another subgroup of the team began developing new ways of measuring trends relevant to sustaining peace. The most promising of these forays to date has been working with data scientists on the development of two types of word lexicons: one for peace speech and one for conflict speech. This has been done by employing machine learning and natural language processing methods to comb through millions of newspaper articles published within highly peaceful and highly conflictual societies. The goal of this initiative is to fill the gap that currently exists for metrics that allow us to better track and therefore promote positive peace.

Finally, we have also been engaging directly with peaceful communities and those struggling to find peace. This has entailed building local partnerships and holding dialogues between our scientists and community stakeholders.

This work began in the Basque region of Spain, a society recently emerging from civil war and hungry for peace, but currently involves working with diverse sets of stakeholders living in Mauritius and Costa Rica. This has taught us about the critical importance of local understanding of some of the key variables.

For example, religious differences can be a source of great divisiveness in many communities. However, in Mauritius, a highly religious nation with large populations of Hindus, Christians, and Muslims, religiosity is tempered by tolerance and taboos around proselytizing, as well as a general belief in the value of spirituality, no matter the denomination. Such contextualization of variables highlights the limitations of the current inclination to employ top-down, one-size-fits-all indices to track and rank national peacefulness, and the need for more locally informed methods.

What peaceful societies have in common

Even a cursory glimpse at our causal-loop diagram of the science on sustaining peace gives you a sense of the highly complex nature of the system of drivers. We have found that there are many different paths to peacefulness through both our review of the science and our conversations with community members living in peace. In fact, most of the societies that currently rank as highly peaceful—the Nordic nations, New Zealand and Australia, Costa Rica, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, the Czech Republic, Canada, and Qatar—came to peace through very different processes and maintain it through distinct means.

However, when our team systematically compared a sample of peace systems with a randomly selected comparison group, we discovered that peace systems tend to share certain commonalities:

- Overarching common identities, such as shared national or regional identities (like Africans, Latin Americans, or Christians) that emphasize commonalities between different ethnic groups.

- Greater positive interconnectedness and independence in the realms of economics, ecology, and security. In other words, they have public spaces, institutions, and activities that bring members of different groups together and help them realize that their fates are closely linked.

- Stronger non-warring norms, values, rituals, and symbols, like commemorations of successful peacemakers and monuments that celebrate the prevention of war. In fact, using a machine learning technique called Random Forest, we discovered that the single most important contributor to peace is non-warring norms, followed in decreasing importance by non-warring rituals, non-warring values, mutual security dependencies, superordinate institutions, and economic interdependence. This suggests that developing norms that are supportive of positive reciprocal social relationships may be more important for peace than previously assumed.

- Peace language in the press. We have been developing a technique to help us measure and track the power of peace speech—peaceable language for building and maintaining more peaceful communities. Our preliminary findings are promising, suggesting that the distinct qualities of conflict vs. peace words in our lexicons are related to the relative “tightness/ordered” versus “looseness/creative” nature of the terms. In other words, journalism in peaceful places seems to employ language of a looser, more open, playful nature, while reporting from non-peaceful societies reflects tighter, more closed, or bureaucratic language.

- A greater degree of peace leadership from politicians, corporations, clergy, and community activists who help establish a vision and set a course toward peace. Peace leadership occurred, for instance, when the Iroquois peace prophet unified five warring tribes and replaced the weapons of war with dialogue and consensus-seeking. Other bastions of peacefulness like Costa Rica and the E.U. have evidenced similar visionary leadership for peace.

Ultimately, we have found that when these different peace variables align and reinforce one another, virtuous cycles are often created that become more resistant to changing conditions. This, we suggest, is the essence of sustainability.

There is still much to learn. We recently launched a short video and a public website that provides an overview of the project and the team, which includes a map locating contemporary societies sustaining peace, an interactive version of the causal-loop diagram that allows users to explore the evidence behind it, and an interactive version of the mathematical model that encourages users to plug in values and play with the model.

In the end, it is vital to remember that peace exists today in pockets all around the globe, and that the more we study and learn from such societies, the higher our chances of building a global peace system for all. Peace is possible—and the more we understand, the more probable it becomes.

Comments