What happens if they take my parents? Will they come into the school to get me? What if they hit me?

Over the past few weeks, these are the questions children have been asking Seattle teachers I know. Many students here are undocumented immigrants or have family members who are.

In a post-election survey of over 10,000 American educators, 80 percent of administrators and school staff reported more anxiety and fear among students. One thousand of these educators named deportation or family separation as a central concern.

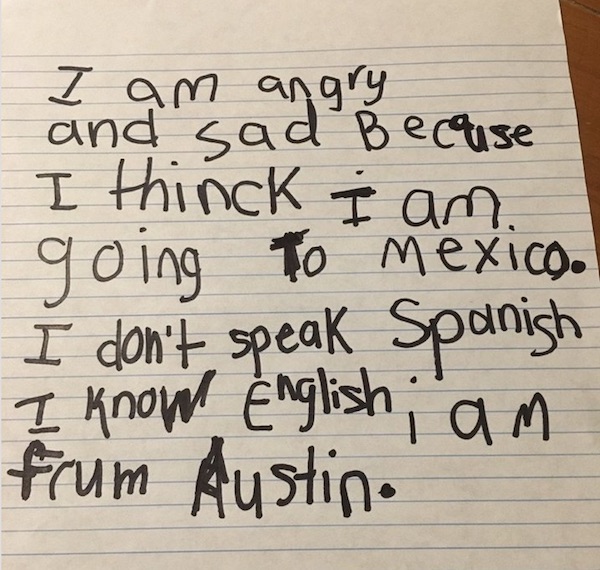

One teacher in Austin, Texas, asked her elementary students to write or draw about their feelings after an immigration sweep there, reported the Huffington Post. “I am angry and sad because I think I am going to Mexico,” wrote one child. “I am so scared,” another wrote.

An elementary school student in Austin, Texas, submits a writing prompt after a series of immigration arrests in February 2017. Source: Huffington Post.

An elementary school student in Austin, Texas, submits a writing prompt after a series of immigration arrests in February 2017. Source: Huffington Post.What can we do to support undocumented immigrant students at this time? How can we provide appropriate resources and strategies to mitigate some of the fear and confusion students are experiencing?

Regardless of whether you have any undocumented students in your classroom, this issue plays a role in all of our lives. Here are a few suggestions for educating and supporting your students.

1. Stay informed

Depending on your state and school district, you may or may not be permitted to openly discuss immigrant rights in your classroom. However, there are resources readily available for undocumented families from the National Immigration Law Center.

In addition site, this guide for educators and school support staff provides tips and tools to help prepare youth and families in the case of an immigration raid.

Consider consulting with local community organizations to discover individuals and groups near your school who could serve as resources for families (e.g., volunteer attorneys, community members, activists, and/or legal counsel at your school district).

However, here is the bottom line. States cannot deny public education to any K-12 student, regardless of immigration status. Under current federal law, all students in your school have a legal right to be there. The teacher’s challenge is to look after students’ well-being and psychological safety: Toward that end, they need to be regularly reminded that they belong in your classroom, and they are safe with you.

2. Give students a voice

Even if you are not permitted to discuss immigration orders in your classroom, you can provide appropriate venues for your students to express their feelings.

For example, have them respond to journal prompts, create artwork, and engage in expressive writing activities that focus on naming thoughts and feelings, as the teacher in Texas did.

Discuss relevant articles and editorial pieces with older students, or lead lessons on differentiating reliable articles and facts from unreliable sources.

One high school teacher I know is designing project-based learning experiences that involve the history of immigration in our country, examining assimilation as a process, and making presentations to school staff about how to be more culturally responsive to different kinds of students.

3. Provide opportunities to de-stress

Of course, your very best lesson plan ideas are useless if children walk into your classroom feeling scared. Educators know that fearful brains are hijacked brains.

Children who feel threatened by authority figures certainly aren’t primed for learning. The brain’s fight-or-flight response compromises the functions of the frontal lobe that involve attention, short-term memory, planning, and motivation.

There are a number of relaxation strategies you can incorporate at the start of the school day or during classroom transitions. Sometimes a brief nervous system “reboot” can be tremendously helpful to your students. (This is obviously good for all students, not just immigrants!)

For example, try a two-minute exercise where you lead students in breathing in for three seconds and breathing out for five seconds. As they practice extending the out-breath, they will be automatically engaging the parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) system, which has a calming effect on their bodies.

For children who are less comfortable focusing on their bodies or their breath, you can adapt these exercises by having them anchor their attention on something external to their bodies like a sound inside or outside the room. Or you can offer them an object to squeeze such as a ball or a piece of clay. Gentle stretches and simple yoga practices can also relieve stress and relax the body. (Some students may benefit from more active movement.)

Remember to make all relaxation practices optional, emphasize movement over focused attention (if you perceive any discomfort with breath practices), and remind students that they are free to keep their eyes open rather than closed during all activities.

Finally, it’s important to be aware of the effects of trauma in your classroom when addressing students’ genuine fears for their safety. This article provides multiple resources for responding to children who are traumatized.

4. Foster group connectedness and belonging

Although relaxation techniques might address an individual student’s tension or stress in the moment, a long-term, classroom-wide focus on connectedness and belonging is crucial.

Students respond positively when we create a sense of trust in our classroom. If students regularly get the message that “we’re all in this together,” they are likely to feel a greater sense of safety.

Here are several practices that you might incorporate to foster connectedness.

- Circle rituals. Many teachers are regularly integrating communication practices to enhance trust and connectedness among students. The book Circle Forward: Building a Restorative School Community walks you through the components of the circle process and presents a wide range of topics and prompts for celebrating successes, sharing gratitude, and discussing anger, grief, race, inequality, and trauma.

- Active listening. Circle practices are designed to create space for active listening, but you can also engage in other concrete exercises to practice this skill.

- Shared identity activities. When students feel alienated and isolated, it’s also important to foreground commonalities and relatedness in your classroom. These two practices, Shared Identity and Reminders of Connectedness, help to set the stage for more empathic responses.

Whether you have 10 or zero students who are undocumented, all students will benefit from listening to each other’s stories and sharing moments of connection.

5. Encourage action

Beyond safety and connectedness, how can we help students to feel a sense of control in their own lives? If we truly want them to play a role in our democracy, we can provide opportunities for positive action and advocacy within our schools.

Now is the time to double down on anti-bullying efforts and focus on developing prosocial behaviors in our school buildings. We can co-create a relationship-centered environment as students, educators, and staff members.

The key here is to focus on methods for encouraging student involvement rather than a top-down approach. These three resources may be useful as you consider your larger school climate.

In this brief video, Californians for Justice introduces an inspiring, student-centered introduction to creating a healthy school climate where all students, regardless of race or status, experience respect and care. How might your students take action in creating a similar approach?

This Speak Up handbook from Teaching Tolerance provides very concrete guidelines for interrupting harassment and micro-aggressions inside and outside of your school. Participate with your students in labeling and addressing harassment in all of its forms.

Finally, research suggests that when peers interrupt a bullying episode, it will likely stop within 10 seconds. If you want to encourage upstanders rather than bystanders, this article shares eight tips for ending school bullying.

If we really are “all in this together,” the fears of undocumented students and their families need to be addressed. By keeping ourselves informed, providing appropriate outlets for students’ thoughts and feelings, nurturing connectedness in our classroom, and encouraging student voices and action, we can foster more relationship-centered schools. More than ever, our immigrant students need to experience a sense of safety and community in school.

Comments