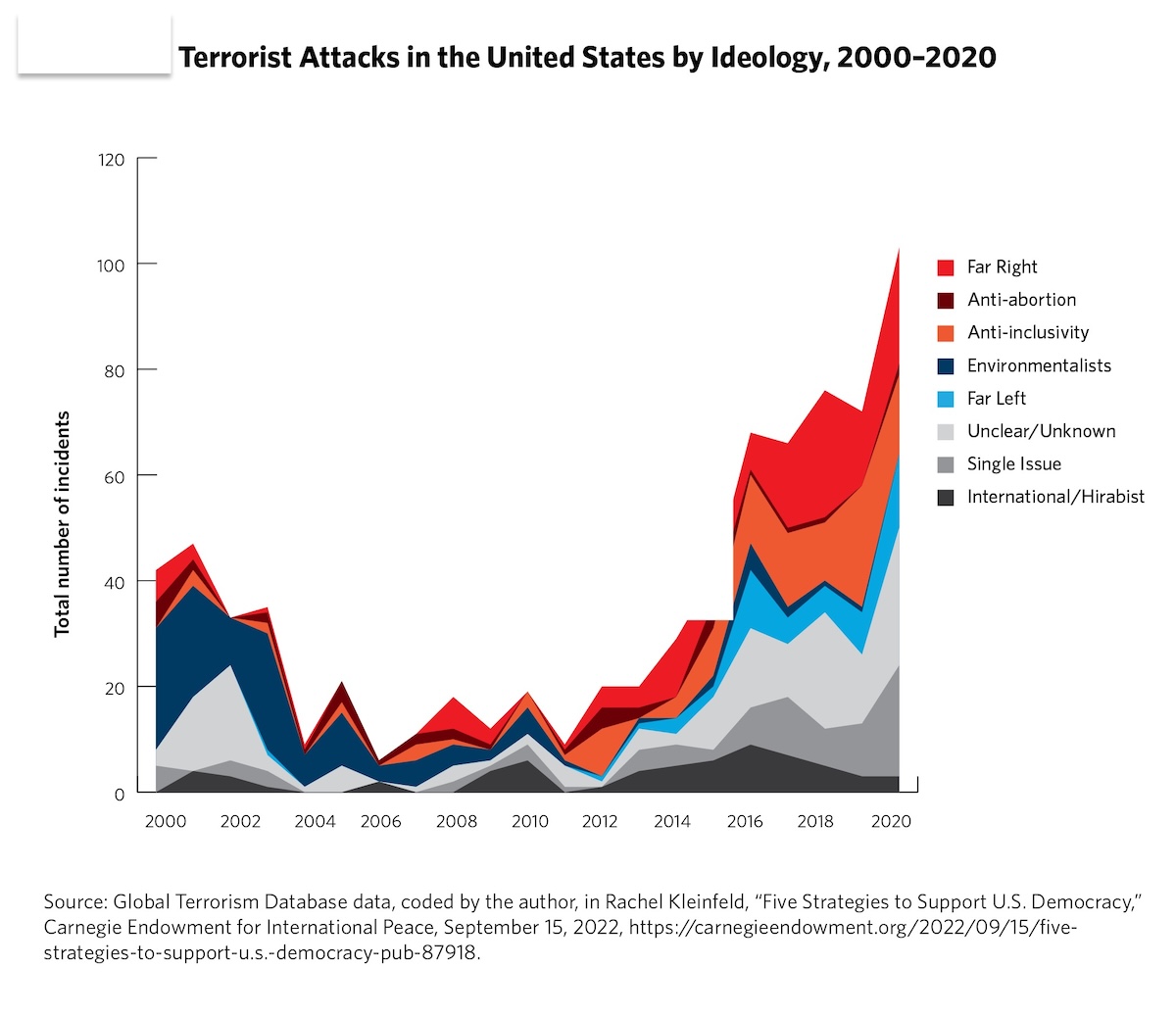

The attempted assassination of Donald Trump highlights a terrible truth: Political violence and support for political violence have been rising in the United States.

Trump himself may bear much of the responsibility for this trend. His entry into American politics triggered a sharp rise in violent rhetoric, which seems to have led inexorably toward violent actions. Acts of stochastic terrorism—that is, violence by individuals operating outside of any organization—have proliferated, with the attempted killing of Trump only the latest example. In fact, threats against lawmakers grew ten-fold since 2016. That trend crystallized on January 6, 2021, when Trump raised a mob of protesters who attacked the U.S. Capitol in an effort to stop certification of Joe Biden as president. Five people died that day, and four responding police officers committed suicide within seven months of the attack.

How many Americans endorse these acts? Approval for the January 6 attack has actually risen among Republicans in the past three years, from 21% to 30%, while those strongly disapproving dropped by almost 20 points. A PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll published in April of this year showed that one in five Americans believe that political violence can be justified at times—a result that is roughly reflected in recent peer-reviewed studies.

The good news is that four out of five do not approve of political violence. It’s also important to note one study that has criticized these results: When a team of researchers based at Dartmouth and Stanford asked 5,000 Americans about support for specific acts of political violence—as opposed to more general support—only 7% endorsed them. Unfortunately, however, even that relatively small group would represent millions of people.

So, what social and psychological forces are at work in our society and our minds when we move from disagreeing with political opponents to actually wanting to harm them? What can we do to coax people in a more peaceful direction? While the association between political rhetoric and violence is not perfectly understood, researchers are starting to map the pathways to pugnaciousness between groups of Americans. We know that political violence can spread, like an illness. Here are eight factors that make infection more likely—and steps we can take to stop it.

1. Aggression

In 2022, political scientists Lilliana Mason and Nathan Kalmoe published a book titled, Radical American Partisanship: Mapping Violent Hostility, Its Causes, and the Consequences for Democracy. With data from two different national surveys, they found that 24 percent of Republicans and 17 percent of Democrats believe that it is acceptable to threaten public officials; among Republicans who believe that Trump should have won the 2020 election, support for violence jumped 10 points. (Note: these numbers have been disputed by other researchers.)

Mason and Kalmoe identified three degrees of violent attitudes: Some people hold views that rationalize harm towards political opponents, others express happiness toward their deaths, and still others endorse outright violence against them. Put together, these are the components of lethal partisanship.

Mason and Kalmoe then looked into various factors to see what might be contributing to these three attitudes. Demographic categories such as gender, age, and education didn’t matter, at least in their studies. Contrary to what some liberals might expect, in these surveys positive feelings toward President Trump didn’t predict more violent attitudes (although note that other, more recent studies have found that so-called MAGA Republicans are much more likely than other Republicans to endorse political violence).

So, what did? By far the biggest predictor of lethal partisanship across the board was having aggressiveness as a personality trait. This isn’t surprising, of course—aggression and violence go hand in hand. But a deeper look at aggression reveals how it fits together with other traits and shapes human behavior. Aggression all by itself is not good or bad; any of us can become aggressive when we face a direct threat. But aggression can go too far when inner and outer restraints are absent.

In neurological studies, more aggressive people tend to show less activation of the default mode brain network, which is associated with empathy and emotion regulation, which in turn helps suppress aggressive impulses. As psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman notes in Scientific American, aggressive people are more likely to retaliate when treated unfairly by others, which is not necessarily a bad thing (“although they tend to care much less about whether others are treated unfairly”).

However, aggression also shapes political outcomes, and it matters when political leaders model and support aggressive attitudes and actions. “Politicians who are more antagonistic get more media attention and are more often elected than more agreeable politicians,” he writes. “In the general population, antagonistic people are more likely to distrust politics in general, to believe in conspiracy theories, and to support secessionist movements.” In a series of experiments published in 2014, Kalmoe found “that exposure to mildly violent political metaphors such as ‘fighting for our future’ increased general support for political violence among people with aggressive personalities.”

Aggression might be more a part of some personalities than others, but it’s also the case that some social situations are more likely to trigger aggression than others. So, what might foster aggression in public life? To answer that question, we must move beyond personality traits to look at group membership and what happens in our groups.

2. Intense partisan identity

After aggressiveness, Mason and Kalmoe found that “partisan identity strength”—how much being Democrat or Republican is part of who they are—is the most important factor in endorsing violence, a factor ratified by many other recent studies.

There are multiple academic papers—mostly from political science and sociology—showing that more Americans are using their political party affiliation as a source of meaning and social identity, with these identities linked to differences in “leisure activities, consumption, aesthetic taste, and personal morality,” as Daniel DellaPosta and his colleagues write in their 2015 paper, “Why Do Liberals Drinks Lattes?”

Worse, the Republican Party has become whiter in recent decades, while the Democratic Party has become more racially diverse—which could be intensifying party antagonism. A recent study of survey data by political scientist Diana Mutz found that nothing predicted support for Donald Trump more than a feeling of threatened status among white Christians—an insight supported by several studies from Robb Willer at Stanford University and the Public Religion Research Institute. As a result, the ideology of Christian nationalism has moved from the fringes of the Republican Party to its center, according to studies by Andrew L. Whitehead and Samuel L. Perry, described in their 2020 book, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States.

“The parties are significantly more racially distinct than they were a few decades ago”

“Indeed, the parties are significantly more racially distinct than they were a few decades ago,” says Mason. The implication is that Americans aren’t just disagreeing about the issues when they talk politics—they may feel a sense of tribal, existential threat when someone disagrees with the positions of their political party. “The relationship between ethnocentrism and violence is abundantly clear cross-nationally and historically,” write Mason and Kalmoe in their paper. It could be that the problem isn’t partisanship, exactly—instead, the truly dangerous ingredient could be the racialization of party affiliation.

“All of the research to date was pointing in this direction,” adds Mason in an interview. “But we have a long tradition of treating partisanship like a largely benevolent force. It makes sense that as an identity grows stronger, and conflict intensifies, people will begin to approve of violence.”

That’s a conclusion reinforced by research conducted by James Piazza, which examined data from 85 democratic countries for the period 1950 to 2018. He “found that increased political polarization raised the probability by around 35% that a democracy experiences more widespread political violence.” He also found that it’s the most partisan individuals who are most likely accept political violence. In his work, this insight applied to both highly partisan Republicans and Democrats.

3. Disinformation, conspiracy theories, and perceived victimhood

Donald Trump entered presidential politics promoting the racist lie that President Obama was born outside of the United States. After he was elected in 2016, large numbers of Republicans embraced the “QAnon” conspiracy theory, which suggests (among others things) that the Democratic Party is run by a ring of Satan-worshipping pedophiles. When Trump lost the 2020 election, he and his followers falsely claimed that the election was fraudulent.

Mourners visit the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA, where eleven people were killed and six wounded in an anti-Semitic attack on October 27, 2018.

© Cam Miller / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Mourners visit the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA, where eleven people were killed and six wounded in an anti-Semitic attack on October 27, 2018.

© Cam Miller / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

All of these lies spread through social media—and they all fueled deadly stochastic terrorism and mob violence, something research predicts. In a 2021 study, Federico Vegetti and Levente Littvay found that those “who score higher on a scale of generic conspiracy belief are also more likely to endorse violent political actions.” That’s a conclusion reinforced by a study published the same year by James Piazza. He used data from more than 150 countries to find “that propagation of disinformation through social media drives domestic terrorism,” largely because it inflames a sense of threat and victimhood in their targeted audiences.

Running through all of these claims is a feeling of declining influence among white Christians, which feeds feelings of persecution. For example, in one 2022 paper, a team of researchers found that “the relationship between Christian nationalism and support for political violence is sharply conditioned by white identity, perceived victimhood, and support for the QAnon movement,” an insight corroborated by another study published in 2022, using different methods and a smaller sample size. These interactions are extensively explored by two Harvard political scientists in their 2018 book, How Democracies Die, which identifies the demographic decline of white Protestants as a major driver of conspiratorial thinking and political violence in the United States.

Of course, it’s not just people with right-wing beliefs who are vulnerable to disinformation, and all people become receptive to violence when they feel threatened or powerless. After the attempt to kill Trump, social media platforms were flooded with conspiracy theories, suggesting, for example, that the assassination was staged by Trump himself to gain sympathy in the wake of his criminal convictions.

Many researchers, thinkers, and technologists have suggested solutions to disinformation, including third-party fact checkers for social media, changing recommendation algorithms, media literacy training in schools, consciously changing social norms to penalize fake-news spreaders, and sanctions against countries that spread disinformation within other countries. But at the end of the day, the solution to disinformation starts with us, and we can start by cultivating intellectual humility: the awareness of our own fallibility. That means verifying facts before you share them, especially when those facts seem to confirm your worldview.

4. Depression and stress

In 2017, Anastasiia Timmer and a team of researchers went door to door in Ukraine interviewing citizens after the Russian invasion of the Ukrainian provinces of Crimea and Donbas. In a 2022 paper, they describe finding that people who are more exposed to war do seem to have a greater tolerance for other kinds of violence, from domestic abuse to intergroup conflict—and the source of this acceptance appears to be stress and depression.

A great deal of other research suggests that “people who report more depressive symptoms are more likely to perceive violent acts as morally acceptable,” says Timmer. That’s an association strongly supported by a 2023 study that investigated “the relationship between depressive symptoms and Americans’ attitudes regarding domestic extremist violence,” like riots or terrorist attacks. Based on two national surveys, they found a strong association of depression (especially in men) with support for political violence and specifically the pro-Trump riot on January 6, 2021.

Additional studies have found that stress and aggression can reinforce each other on a biological level. As those researchers note, “Depression reached unprecedented levels during the COVID-19 pandemic,” mainly as a result of increased isolation. Thus, they argue, based on their findings, we shouldn’t be surprised to see rising support for political violence (and conspiratorial beliefs).

As the researchers note, depression in itself cannot explain rising political violence—but as theirs and other studies suggest, a more stressed and depressed population appears to be more vulnerable to the appeal of violence. One of the positive implications is that investing more in mental health care and social connection could reduce support for violence.

5. Anger, contempt, and disgust

While Mason and Kalmoe’s study gives us some sense of how common the tendency to accept political violence is—and some of the personality traits and belief structures that may be associated with it—a 2015 study points us in the direction of the emotions involved.

In “The Role of Intergroup Emotions in Political Violence,” San Francisco State University researchers David Matsumoto and Hyisung C. Hwang and the University at Buffalo’s Mark G. Frank tried to figure out which emotions can drive violence by a group against an outgroup.

Former Metropolitan Police Officer Michael Fanone, badly injured in defending the Capitol on January 6th, speaking at the Courage for America event by the Capitol Reflecting Pool on January 5th, 2023, against political violence.

© Victoria Pickering

Former Metropolitan Police Officer Michael Fanone, badly injured in defending the Capitol on January 6th, speaking at the Courage for America event by the Capitol Reflecting Pool on January 5th, 2023, against political violence.

© Victoria Pickering

They examined the emotional tone of major political speeches that occurred prior to political events throughout history, looking at the emotions expressed in words, the judgments underlying the emotions, and the nonverbal expression of the emotions that could be seen in video form.

They also examined speeches made by “ideologically driven” leaders who despised opponent outgroups that resulted in violence, such as Hitler’s; and they studied those that did not, like Gandhi’s Salt March and pro-Tibet protests at the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

They found that speeches which preceded violent events tended to express more anger, contempt, and disgust (ANCODI)—but not fear, happiness, sadness, or surprise. These negative emotions tended to target specific outgroups—Jews, in the case of Hitler’s speeches.

The “amount of anger, contempt, and disgust expressed nonverbally by violent-group leaders correlated significantly only when they referenced the opponent outgroup; they did not correlate when the violent-group leaders referenced something other than their opponent outgroup,” note the researchers. In the months before major non-violent events, anger, contempt, and disgust actually declined.

The researchers suggest that the ANCODI model may be a way of monitoring the expression of emotions by group leaders that could provide an early warning of looming violence. They also propose that interventions to prevent violence could be measured by how effective they are in reducing ANCODI emotions. One important caveat of the study the researchers concede is that they looked at group behavior. “We do not know if this phenomenon applies to individual acts of violence,” they write.

Much more recent studies have applied these insights to different countries and social situations, and highlighted the special role of disgust in driving intergroup violence. For example, David L. Rousseau and his colleagues ran a series of experiments which found that “only disgust reactions consistently produced dehumanization and support for human rights violations against outgroups.” One of the implications of this work is that political leaders—and, indeed, all of us—should strive to avoid expressing anger, contempt, and especially disgust against political opponents, if we wish to avoid violence.

6. Firearm ownership

The best evidence to date suggests that all by itself, gun ownership is not associated with political violence or support for political violence. But there are some distinctions among gun owners that do seem to matter.

A paper published in April of this year surveyed 12,851 Americans about firearms, political attitudes, and violence. They found that “firearm owners were only moderately more supportive of political violence than nonowners”—but that within the group of owners, people who bought guns in the wake of the 2020 election and those who always or nearly always carried firearms in public “were more supportive of and willing to engage in political violence than other subsets of firearm owners.” Almost 42% of assault-type rifle owners said political violence could be justified.

These attitudes have real-world consequences. From 2020 to 2021, the number of armed pro-Trump demonstrations rose from 6.2% to 8.8%; during the same period, only 1.5% of all other demonstrations involved firearms. As a 2021 report from the Bridging Divides Initiative found, those armed demonstrations were 6.5 times more likely to lead to violence than those without firearms.

Which leads us to the common-sense truth that more guns mean more gun violence. Shortly after the attempt on Trump’s life, the satirical site The Onion ran one of their funny-because-it’s true headlines: “Investigation Finds Secret Service Failed to Account for Nation’s 393 Million Guns.” Decades of research reveal that the more guns in a state, county, city, or neighborhood, the more likely you are to be killed or injured by a person with a gun. There are no peer-reviewed studies that say otherwise. The 20 year old who took a shot at Trump had “borrowed” his father’s semi-automatic rifle: the AR-15, which is owned by 5% of Americans and has been used in 10 of the 17 deadliest mass shootings in the United States.

While limiting the supply of guns may not stop political violence in America, it stands to reduce its probability—and could also make any violence less deadly.

7. Moralization and moral convergence

In 2015, Baltimore witnessed mass protests after a man named Freddie Gray died in police custody. A small number of these protests turned violent.

A protest at the Baltimore Police Department following Freddie Gray's death.

© Veggies / CC BY-SA 3.0

A protest at the Baltimore Police Department following Freddie Gray's death.

© Veggies / CC BY-SA 3.0

In 2018, a team of five researchers searched the social media platform Twitter (now called X) for tweets about the Baltimore protests. They wanted to investigate “moralizing” tweets—that is, tweets that viewed the protests as a moral issue rather than as a political disagreement. A moralizing tweet might, for example, refer to people as “disgusting” or “evil” or “traitorous.”

In fact, they did find a positive association between the number of moral tweets and the occurrence of violent protests (gauged with arrest data). “The days in which there were violent protests, we saw that there was a lot more moral language being used,” says study coauthor and University of Southern California Ph.D. student Joe Hoover. “Which was consistent with the idea that morality and violence in these contexts might be linked.”

The team also ran an experiment using another prominent protest marred by violence: the far-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017. Respondents were asked to what extent they thought protesting against the far-right demonstrators was a moral issue; they were then asked how acceptable it was to use violence against these far-right activists. What they found is that people were more likely to embrace violence the more they saw it as a moral issue.

In an additional experiment, the participants were given the same prompts, but they were told either that the majority of Americans agreed with their view of the protest, or that few Americans agreed with their view. They found that “moralization predicted violence only when participants perceived that they shared their moralized attitudes with others.”

In other words, when it comes to violence, there’s validation and safety in numbers. The researchers dubbed this phenomenon “moral convergence,” when many people come together around a strong idea of what’s right and what’s wrong. The “risk of violent protest, in other words, may not be simply a function of moralization, but also the perception that others agree with one’s moral position, which can strongly be influenced by social media dynamics,” they write.

Of course, our groups often do good, as well. Hoover concedes that moralization, moral convergence, and violence don’t always have to be linked. Some of the most disciplined nonviolent movements in American history have been highly moralistic. For instance, the Civil Rights Era Southern Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the American South trained its activists to not respond violently even if attacked.

“We are thinking about these factors as risk factors,” says Hoover. “Certainly, there have been many protests where participants held a strong moral position and surely perceived moral convergence and there was no violence.” Moralization and moral convergence are like kindling, but “you still need a spark; you need something to actually light the fires.”

Hoover suggested that police could play a positive role in preventing protest violence by practicing de-escalation that makes clear they respect the protesters’ ability to be heard. As the research by Matsumoto, Hwang, and Frank suggests, leaders also have a responsibility to not fuel anger, contempt, and disgust.

8. Group leadership

When it comes to violence, leadership matters. There are many, many studies—starting with Stanley Milgram’s classic electric-shock experiments—which show that people are much more likely to inflict pain on others when an authority figure tells them to. When leaders engage in violent rhetoric, so do their followers; when they urge calm, people do calm down. Research has documented that words do have an impact on both beliefs and behaviors.

Carlos Curbelo speaking at the 2014 Conservative Political Action Caucus.

© Gage Skidmore / Wikipedia Commons

Carlos Curbelo speaking at the 2014 Conservative Political Action Caucus.

© Gage Skidmore / Wikipedia Commons

For example, a 2017 Polish study found “frequent and repetitive exposure to hate speech leads to desensitization to this form of verbal violence and subsequently to lower evaluations of the victims and greater distancing, thus increasing outgroup prejudice.” As part of the study, researchers surveyed participants on how frequently they encountered hate speech against refugees; they found that those who were more exposed to hateful words were more prejudiced against the group and more accepting of restrictive immigration policy.

Taken together, these studies suggest that our political leadership—everyone from pundits on cable news to the President of the United States—would do well to avoid promoting the political tribalism that leads people to strongly identify with one group and demonize the other. They could also reduce the use of angry, contemptuous, and disgusted rhetoric to refer to political outgroups. And Americans everywhere could learn to rely less on the echo chambers of social media, where moral convergence and affirmation can fuel violence against people and property. Most importantly, we have to be able to stress civility and humanity toward the other side, even when it’s difficult.

In 2018, Florida Republican Congressman Carlos Curbelo received a threatening tweet. “I will kill Carlos Curbelo,” wrote a 19-year-old constituent named Pierre Alejandro Verges-Castro.

“What Pierre did is very serious,” Curbelo told the Miami Herald. “We have two young daughters and like any family, we worry about our safety and security, especially in light of all the acts of violence we are seeing throughout our country.” Despite these fears, Curbelo chose to reach out to Verges-Castro and held a joint press conference with him where he publicly forgave him. Although the teenager was arrested by the FBI, the congressman stressed that he doesn’t want the incident to tar him for the rest of his life. As Curbelo said:

Let us be respectful and sober in our conversations, our debates, and especially in our social media interactions. And as for Pierre, I wish him the best. He made a mistake, and his life shouldn’t be ruined because of it. I truly believe in second chances. I am hopeful Pierre will become a model citizen who is now in a unique position to be a part of the force for healing that our community and our country so desperately need.

In the wake of the assassination attempt on Trump, both Republican and Democratic leaders acted to calm followers. “We’ve got to turn the temperature down in this country,” said Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson on NBC. That same day, President Joe Biden addressed the attack on national TV: “There is no place in America for this kind of violence—for any violence. Ever. Period. No exception. We can’t allow this violence to be normalized.”

This article was originally published on November 7, 2018. In the wake of violence during the 2024 presidential election, it was revised to address current events and expanded to include new research.

Comments