At a time of extreme political polarization, heightened racial tensions, and cross-cultural conflicts in the United States (and beyond), how can we encourage Americans to build relationships with—or even just try to understand—people who have different backgrounds or views from their own? And how can scientific research help us chart a positive path forward for our multi-racial, multi-ethnic democracy?

Attendees at the “Research to Impact” convening

Attendees at the “Research to Impact” convening

Those were some of the big questions that a group of researchers, practitioners, funders, and storytellers gathered in Chicago to explore earlier this fall. This “Research to Impact” convening was cohosted by the Greater Good Science Center (GGSC) and four other organizations: More in Common, the Center for the Science of Moral Understanding, Over Zero, and the New Pluralists funder collaborative. The event centered on a belief in the power of “pluralism”—that our country’s strength lies in its ability to build unity amid diversity.

“Pluralism offers a choice: to harness the power and creativity inherent in our diversity rather than let it seed chaos and disruption,” said Lauren Higgins, New Pluralists’ director of ecosystem strategy, during the convening’s kickoff panel discussion. “Pluralism encourages us to evolve beyond zero-sum thinking towards fostering communities of belonging.”

In his talk at the event, Justin Gest, a political scientist at George Mason University who recently coauthored a report on the factors that promote pluralism in America’s diversifying democracy, emphasized that the goal of cultivating a society that celebrates diversity hinges on redefining our national identity and embracing the full spectrum of who we are.

“It requires a vision bold enough to transcend mere tolerance, aiming instead for the richness of our celebrated differences,” he said.

So how do we do that? The event featured talks by social scientists whose work offers a way forward. A main goal of the program was to put research insights into the hands of people who can apply them to their work promoting pluralism in communities across the U.S. and around the world. In an effort to help spread these practical findings as widely as possible, below I share three key insights that I took away from the event.

1. Ambiguity breeds prejudice

Art by Dpict, live-scribed at the "Research to Impact" convening

Art by Dpict, live-scribed at the "Research to Impact" convening

In his insightful presentation, Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton, a psychology professor at UC Berkeley and senior faculty advisor to the GGSC, highlighted a crucial factor in societal divisions: ambiguity. He explained that in unclear social situations, we often default to stereotypes and preconceptions to fill in the gaps, making “ambiguity a breeding ground for prejudice.”

A study by psychologists John Dovidio and Sam Gaertner illustrates this concept. They looked at how people assess job candidates based on their resumes. When a candidate’s resume indicated that they were clearly qualified or unqualified for a job, the hiring decision corresponded to those qualifications. But when their qualifications were ambiguous, the decision was more strongly associated with the candidate’s race, with people showing preference for white candidates over Black candidates. In other words, when the situation was ambiguous, people seemed to fall back on racial biases and assumptions to help guide their decisions.

“In situations ripe for interpretation, our hidden biases can shape our decisions without our realizing,” said Mendoza-Denton. To address this, he emphasizes the principle of “clarity as equity.” In his own research within academic settings, he found that clarity—defined as the transparency and straightforwardness of organizational rules, roles, and expectations—plays a crucial role in ensuring equity.

Too often, organizations don’t share information—such as by providing clear guidelines on academic progress, making support resources readily available, and making success criteria totally explicit—in ways that are equally transparent and accessible to all members of a department, with discrepancies often based on an individual’s cultural background.

That lack of clarity can inadvertently breed prejudice and inequities as people fall back on assumptions and biases for guidance. “Ensuring clarity in a department means that every individual, irrespective of their background, has equal access to all vital information and resources,” Mendoza-Denton explained.

He concluded with a thought-provoking question: “How can we work towards elucidating the unspoken and unseen elements within our environments or structures that may be breeding grounds for prejudice?” This approach not only fosters a sense of fairness and trust among community members but can also promote effective collaboration by removing ambiguities that can lead to biased perceptions and decisions.

2. We think we know how “the other side” sees us—but we’re wrong

Moving from internal biases to external misunderstandings, Nour Kteily, codirector of Northwestern University’s Dispute Resolution Research Center, discussed the concept of “meta-perceptions,” how we think “the other side” thinks about us. Research finds that these assumptions are often way off, with people from both sides thinking they are perceived more negatively than they really are.

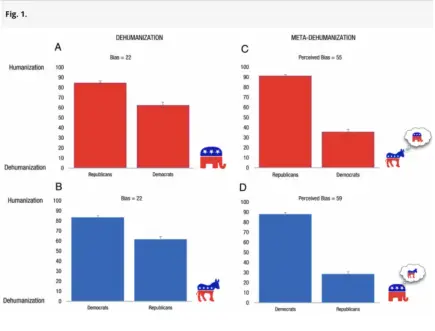

One of the studies cited by Kteily, led by Samantha Moore-Berg of the University of Utah, focused on meta-prejudice and meta-dehumanization among American partisans. It indicated something that’s not new to many: that both Democrats and Republicans harbor similar levels of dislike and dehumanization toward each other. However, it also pointed to something surprising: Each group overestimates the negativity that the other side feels toward them.

For example, when Republicans had to rate (on a scale of 0 to 100) how “evolved and civilized” they find Democrats to be, their average score was just above 60—-but Democrats believed that Republicans’ scores would actually be a little more than 30, meaning that Republicans’ feelings toward Democrats were about twice as positive as Democrats thought. The same was true for how Republicans believed Democrats would view them. This mistaken belief—that the other side views them more negatively than they actually do—makes both groups think they are more divided than they really are.

On her website, Moore-Berg explains that these meta-perceptions contribute significantly to the desire for social distance from opposing party members and to support for policies that threaten democratic norms in favor of one’s own political group. However, she offers a hopeful insight: “Because meta-perceptions are largely inaccurate, they can be intervened on.”

© Moore-Berg et al., 2020

© Moore-Berg et al., 2020

Sure enough, research does suggest ways to correct these distorted perceptions. A collaborative study by Moore-Berg, Kteily, and others showed that increased positive interactions (rather than just more interactions) with members of opposing groups markedly reduced “meta-dehumanization”—the belief that those other groups view your group as less than human.

This finding was illustrated in a video project where more than 1,200 Americans from diverse backgrounds were shown real data about how another, potentially opposing group actually views certain policy issues.

Taking immigration as an example, participants rated their stance on a spectrum from “open” to “closed” borders and then guessed what someone from the opposing party would assume their stance to be. For the most part, they wildly overestimated how extreme the other party would assume their views to be—but upon seeing the actual data, they realized their misjudgments.

Reflecting on this, one participant remarked, “There’s so much more overlap than I think we realize.” Another observed, “The narratives on TV and social media don’t reflect this reality!” Kteily emphasized the power of acknowledging these misperceptions, highlighting how such realizations can ease fears, transform attitudes, and foster more effective communication.

3. Promoting contact between groups is important—with the right conditions

Art by Dpict, live-scribed at the "Research to Impact" convening

Art by Dpict, live-scribed at the "Research to Impact" convening

Addressing the challenges identified by other researchers, Linda Tropp, a professor of psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, offered reasons for hope and optimism, with some caveats.

Decades of studies have found that fostering contact between diverse groups is a powerful tool for reducing prejudice and nurturing trust. In her presentation at the event, Tropp, a coauthor of a comprehensive review of hundreds of other studies on this subject in 2006, discussed the well-documented benefits of such interactions. According to her research, contact between people from different groups tends to lead to less prejudice and reduced feelings of threat between those groups, as well as lower anxiety about engaging with someone from another group. Most notably, it promotes greater trust and empathy between members of different groups.

However, she acknowledged the challenges in implementing effective strategies for bringing people into contact with one another.“How can we expect people to be truly open to others’ perspectives if they feel threatened?” she asked. Highlighting the need for environments that dial down anxiety, Tropp laid out a few key factors to increase the odds that contact will actually be effective:

- Promoting sustained and active engagement. She stressed the importance of continuous, active engagement rather than one-off events. “Trust and understanding grow over time, requiring deeper and more frequent interactions than a single day’s encounter,” she said, emphasizing that transformative change stems from sustained effort. “It’s the repeated, ongoing interactions that plant the seeds of understanding and allow them to flourish.”

- Focusing on shared goals. In tense or conflicted settings, Tropp advocates for collaborative projects centered on common goals. “Engaging in shared community projects, like enhancing public spaces, provides a neutral platform for interaction and reduces anxieties,” she said. This strategy of working toward a shared objective leverages common interests to foster positive intergroup interactions, subtly shift perceptions, and promote mutual understanding.

- Recognizing diverse starting points. It is crucial to understand where the participants are coming from. “Not everyone comes to the table from the same place,” explained Tropp. “Some are open and ready, while others, whom we might call the movable middle, might be more hesitant or skeptical.” The success of contact initiatives may initially manifest in subtle shifts—hostility giving way to neutrality or indifference blossoming into curiosity. By recognizing the diversity of starting points and nurturing the journey with patience and intention, we can ultimately make more progress.

These three insights—embracing clarity, understanding our misperceptions, and strategically promoting contact between groups—can help remind us that the pursuit of a pluralistic society is entirely possible, if we’re willing and able to turn this research into action.

Comments