We are weeks away from the U.S. presidential election—and every other lawn in my Berkeley neighborhood has been taken over by political yard signs for school board positions, our hotly contested district seat, and a whole alphabet range of propositions.

But there are barely any signs for our red-and-blue presidential candidates.

I did see 10 yellow yard signs staggered along University Avenue, a main street in our city of 120,000. It said, “Vote for Rubber Ducky, More Quack, Less Whack.”

To me, that prank captured how exhausted so many people feel about politics. A new study suggests that most people feel that way—and argues that this presents both a crisis and an opportunity.

Hidden tribes of America

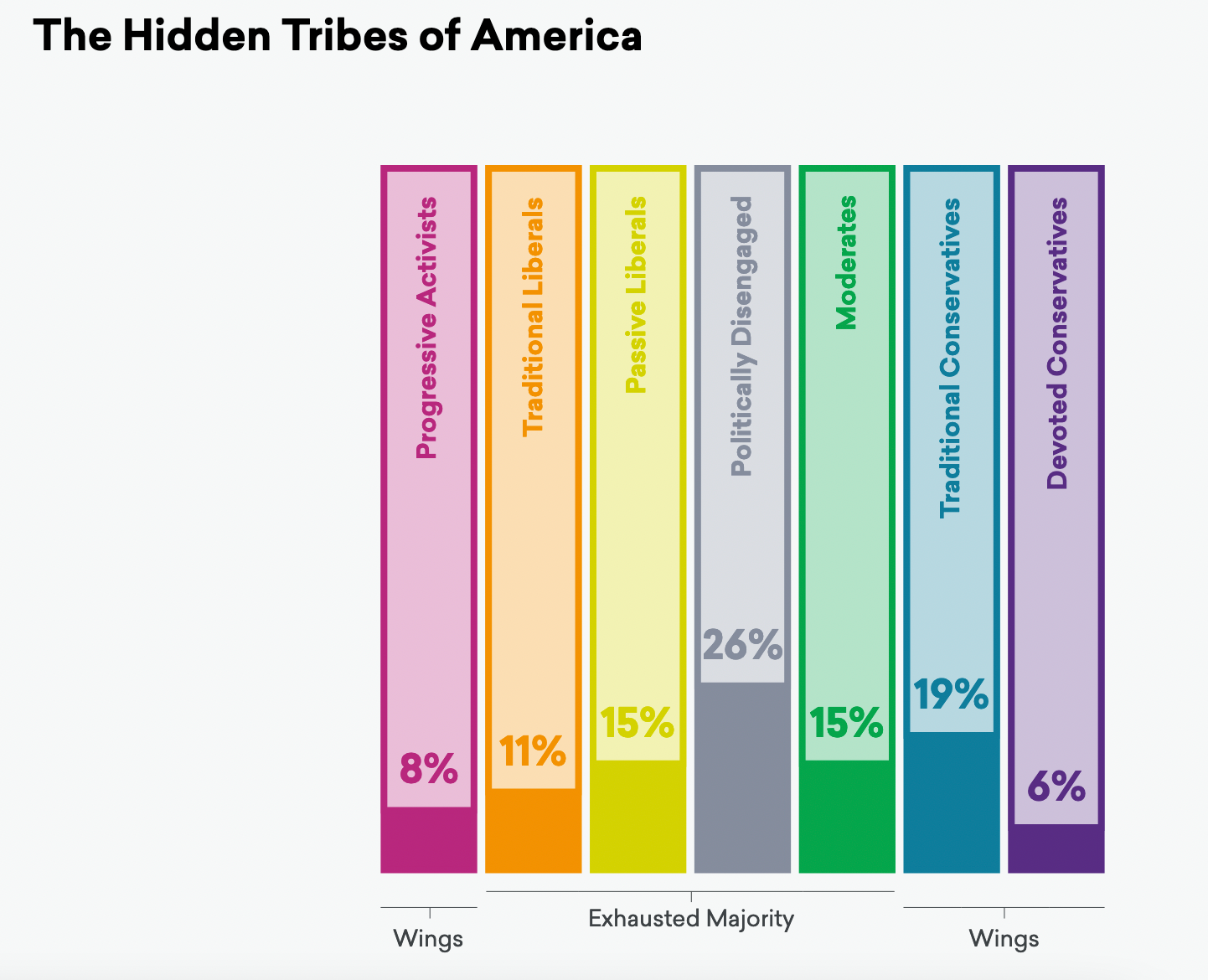

More in Common is a nonprofit organization that tries “to understand the forces driving us apart, find common ground, and bring people together to tackle shared challenges.” You might recognize the name from its blockbuster “Hidden Tribes” report, which in 2018 identified seven distinct political groups within America.

That report stipulates that five of the seven tribes, representing roughly 67% of the American public, make up the so-called “exhausted majority” fed up with the left-right divide. More in Common researchers argue that while partisans score political points, members of the exhausted majority are so frustrated with our politics that many have checked out completely, ceding the floor to more extreme participation.

Their framing has a sophisticated way of approaching polling, but some political scientists believe polarization in the American people, as we understand it, is a myth.

“Politics is a remote interest for many Americans. Most Americans are busy living their lives, doing their jobs, raising their children, and having a little recreation. They don’t spend a lot of time thinking about politics or absorbing political news,” says Morris Fiorina, a political science professor at Stanford University who is the author of 14 books, including Unstable Majorities. Fiorina has been studying representation, public opinion, and elections for 50 years.

Most Americans are exhausted by politics and don’t feel represented. But Fiorina believes our very political system is to blame. Politics in America has evolved into an era of “unstable majorities” run by a small “superpolitical” segment. He contends that polarization in the American people isn’t sustaining this group; it’s our very political system that is offering only two parties that are increasingly more partisan.

“The parties have sorted towards the extremes, each party has become more homogeneous internally on ideology and policy and more distinct from the other,” says Fiorina. Voter behavior has not changed much over the decades because the alternatives that voters face have not changed.

Fiorina explains that we’ve nationalized politics so that now Oregon Republicans and Ohio Republicans have exactly the same agendas; and New Mexico Democrats and Massachusetts Democrats have exactly the same agendas. “Texas money is going all over the country for Republicans and Hollywood money is going all over the country for Democrats, and so they are imposing national agendas on races where they probably don’t really fit the interests of the districts.”

And that’s why he believes political participation in the country is run on the extremes. “There are about 15% for whom politics are a consuming interest; these are the people who participate in campaigns, who give money, and comment on social media.”

Researchers refer to these superpolitical groups as “the wings.”

The wings that two-party systems fly on

“The fact is these people on the wings are influential, they pull the parties to the right and left,” explains Fiorina. “The fact that they are a small number, it doesn’t matter. Politicians weigh votes and these people’s votes weigh more.”

If you want to understand why someone might be part of the wings, there are three broad trends that run parallel to polarization, according to More in Common director of research Stephen Hawkins: a decline in institutional trust, a drop in sense of belonging and community, and a change in information systems, or increasing echo chambers enabled by cable news and social media.

Since the superpolitical get much more airtime and traction, we get a very inaccurate view of politics. If you look at the aggregate distribution of ideology or opinion in the U.S., it hasn’t changed since Jimmy Carter’s days in 1976. What has changed is the way the parties organize politics. It used to be that the Democrats and Republicans were both big heterogenous parties, making building cross-party coalitions easy.

“It is simply the case now that the Democrats have become a solidly liberal party and Republicans have become a solidly conservative party. Which has made solving any kind of issue in politics very difficult,” explains Fiorina.

The extreme wings have made moving the political needle impossible.

We are in an era of “unstable majorities”

In between the wings stand everyone else, who constitute the majority.

“The exhausted majority is a group that refers to two-thirds of Americans who feel frustrated by the political conversation, who are not ideologically oriented, but are more flexible in their political beliefs, who don’t feel well-represented by the political debate and are open to finding compromise in the political conversation,” says Hawkins.

“It’s a group that is quite varied demographically, it’s a group that is defined not by what it is, but what it is not, and it is not deeply enmeshed in ideological conflict and partisanship orientation. Instead it wants to see the country succeed, instead of one party succeeding.”

The U.S. is currently experiencing a historically unprecedented period of electoral instability. Fiorina’s research draws contrasts with earlier periods in American electoral history and explains how the sorting of the two major political parties into ideologically opposing organizations not only does not represent the larger electorate—it results in the inability of either party to forge lasting majorities.

This is partly by design. But political scientists say it’s a mystery how we evolved European-style parties into a two-party system. “We don’t fully understand how we came to this and we don’t really understand how to get out of this,” says Fiorina.

The architecture of our political decision making is one that does not permit for people to express moderation, they have to pick a camp, says Hawkins. “In other countries, with the exception of the U.K., there is far more capacity for political subcultures to manifest in voting. We aren’t really polarized, we just don’t have choices.”

A majority of the world’s developed democracies are parliamentary. That’s when a party or coalition of parties gets a majority of seats in the parliament, and chooses the chief executive, often called the prime minister. The U.S. is one of a minority of democracies that are presidential, in which voters elect the chief executive independent of the legislatures.

The U.S. is even more unusual in having two equally powerful chambers of the legislature, which are elected separately for different terms of office. The two-year term served by members of the U.S. House is the shortest among world democracies; elsewhere, four- to five-year terms are common.

Fiorina’s research shows that, because of these exceptional institutional features, a national election every two years can generate eight patterns of institutional control of the presidency, House, and Senate, and six of those eight patterns can lead to a divided, gridlocked government with an unstable majority.

Only two patterns can lead to full party control. Historically, we had a lot more of that; 1896 to 1930 was our era of Republican majorities, with the party often winning all three power centers. Then we swung to the era of Democratic majorities, with the blue party often winning all three power centers until 1950. After that, we entered into 40 years of divided governments that still got things done. But from 1990 onward, Fiorina contends we’ve been in an era of unstable majorities. “The result is not a 50–50 nation, but something more like a 30–40–30 nation,” explains Fiorina.

There have been exceptions. The 2016 elections generated a rare shift to a Republican presidency and Republican-run House and Senate, but that enabled a lot of real swings to the right that don’t represent most Americans.

Most voters are not party elites, and most voters are not very partisan at all. So they are increasingly dissatisfied with the choices the political system offers.

“With close electoral competition between two ideologically well-sorted parties, political overreach has become endemic, resulting in predictable electoral swings,” says Fiorina. “Parties attempt to govern in a manner that reflects the preferences of their bases, but doing so alienates the marginal members of their electoral majority, who then withdraw their support in the next election.”

Overreach is now a regular feature of politics today.

We aren’t polarized, but our system is polarizing

Fiorina has been studying the data on abortion opinion for decades. Most Americans actually supported Roe v. Wade when it was in place. Following a Trump appointment during his presidency, the Supreme Court reversed the decades-old decision that protected a woman’s right to choose an abortion.

He says, “There is a disconnect between the government’s agenda and what the country believes. Only the highly involved, for example, think abortion is an easy issue. But 85% of the country says it is complicated.” Fiorina says most data show there is much more common ground on issues than people believe.

Hawkins agrees that our political system is a binary. “We have a red and blue party and you have to pick one of those when it comes to voting.” Even if there are seven major cohorts of Americans in terms of their political beliefs, as his report explains, he says at the end of the day people have to cluster into one of three places: “Either they don’t participate or they pick the Republican or pick the Democrat.”

The rising importance of social issues, like abortion or same-sex marriage, has aggravated the polarization.

“As long as politics was about nothing but economics, the two-party system worked, but the social issues are harder to pick one side on,” says Fiorina. “We are in an era where politics is about everything, the personal is politics, and it’s become really difficult for a two-party system. How can two parties incorporate economics, social issues, foreign policy, they can’t. They can’t come up with something that appeals to the entire country.”

The upcoming election

So how is this going to play out in the coming weeks? Fiorina is pessimistic: “This election is ugly. The outcome is going to satisfy no majority.”

Even so, Hawkins believes Harris’s campaign is very much veering toward the center and toward the exhausted majority. “Her campaign is taking for granted that the progressive activists’ wing on the far left will show up and vote against Donald Trump, even if they think Kamala Harris is not sufficiently committed to policies of social justice—but the election is hinged towards whether she can win over more moderate votes.”

In analyzing the DNC speeches, Hawkins finds that there was very little mention of narrow group identity. For example, Harris has made very little mention of her gender and her race in her candidacy, unlike how Obama ran 16 years ago or how Hillary Clinton ran eight years later with “I’m with her.”

“So it seems they are focusing on her appeal as a policymaker, as a leader, someone who can solve problems of the economy and immigration, rather than trying to use the language of progressive activism,” argues Hawkins. “Yes, they are trying to reach the exhausted majority.”

Will that be enough to make a difference? At this point, it’s hard to say. But it may plant the seeds for something down the road that will help energize a majority of voters, instead of just making them feel tired.

Comments