When grappling with the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the students in a seventh-grade science classroom in northern New Jersey wrestled with a question: How do we ensure that all community members have equitable access to much-needed resources after international weather events?

The storm had left the town’s only supermarket without power, creating a need for food over the next two weeks. Working in small groups in a science classroom, students were challenged to design a greenhouse prototype out of recyclable materials that could grow food year-round. This sustainable structure could potentially supply food throughout the year and during another prolonged power outage.

As educators, we are nurturing tomorrow’s leaders, who will be called upon to solve global problems like climate change. And in order to do that, they must learn ethical thinking. But how do we teach ethical thinking in the classroom without making it feel like an additional instructional task for teachers?

At the Rutgers Social-Emotional Character Development Lab, we have developed a step-by-step framework that builds upon principles of social-emotional learning (SEL) that you may already be teaching in your classroom—as well as established processes for problem solving and decision making—to help students examine real-world issues through an ethical lens. Research suggests that these kinds of lessons can help students grow into global citizens with the skills to address the big issues our world is facing today.

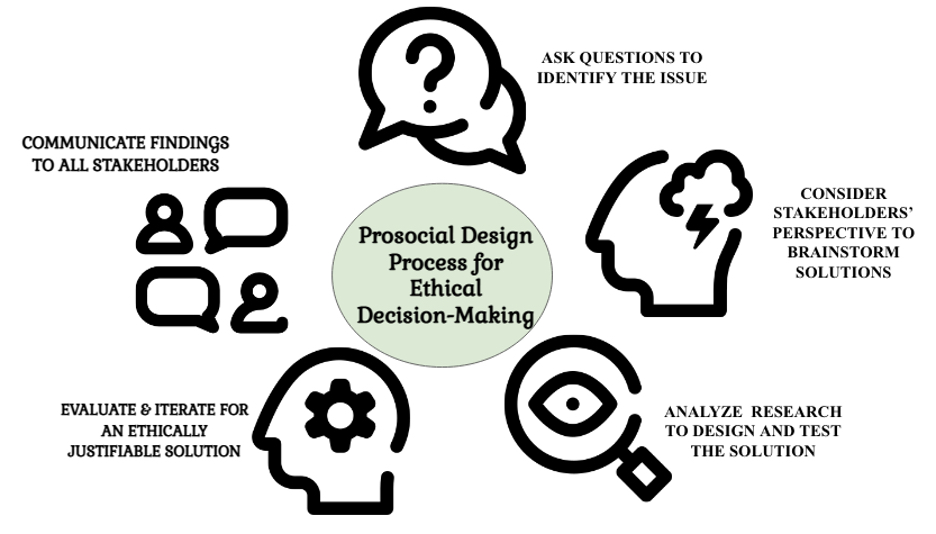

Five steps for ethical decision-making

Teaching ethical thinking aligns with the mission you may have as an educator to promote global citizenship. “Being a global citizen means understanding that global ideas and solutions must still fit the complexities of local contexts and cultures, and meet each community’s specific needs and capacities,” explains AFS-USA. While investigating real-world problems from many perspectives, students gain an appreciation for many sides of an issue and avoid the pitfall of simply reinforcing their preexisting attitudes.

Ethical thinking also enriches social-emotional learning. According to researchers Michael D. Burroughs and Nikolaus J. Barkauskas, “By focusing on social, emotional, and ethical literacy in schools educators can contribute to the development of persons with greater self-awareness, emotional understanding and, in turn, the capability to act ethically and successfully interact with others in a democratic society.” The five steps below serve as a seamless way to integrate ethical decision making into a science or STEM class.

These steps come from our Prosocial Design Process for Ethical Decision-Making, which itself is a synthesis of three frameworks: prosocial education (which focuses on promoting emotional, social, moral, and civic capacities that express character in students), the Engineering Design Process (an open-ended problem-solving practice that encourages growth from failure), and the IDEA Ethical Decision-Making Framework. This process offers a way for students to come up with creative solutions to a problem and bring ethical consideration to global issues.

1. Ask questions to identify the issue. Students begin with a current topic, like climate change, genetic engineering of crops, the use of insecticide to control pests in agriculture, oil spills in the ocean, or deep sea mining.

Then, they reflect on open-ended questions as a way to start thinking about a solution. For example, they might ask, “What is the ethical issue?” to envision the problem and consider the perspectives of those involved in the problem.

Let’s imagine how this process might work in the seventh-grade classroom mentioned above. First, students may contemplate how equity plays a role in the distribution of resources during a natural disaster like Hurricane Sandy. One student, Naya, recounts how her family only had access to canned goods during the two-week power outage, as they could not afford the grocery store prices for the limited items kept frozen by a generator. This prompts her to pose the following question to her group: “How will we make sure that the food grown in the greenhouse is equitably distributed? Who will pay for the materials to build and maintain the greenhouse?”

To deepen the inquiry, group members might ask additional questions, such as “Who are we creating a product for, and why is it important to find a solution?” and “What are the power dynamics at play in this problem?” As students engage in discussion, they are practicing teamwork and learning to advocate for the rights of others—SEL skills that help them to consider the perspectives and diverse needs of all people affected with an inclusive ethical lens.

2. Consider the perspectives of people impacted to brainstorm solutions. In this step, students engage in open and honest dialogue on how the problem can affect individuals, groups, and wildlife in the community.

In the Hurricane Sandy example, some students talk about how much pressure the mayor has to ensure that response efforts run smoothly and equitably, and that all members of the community have the necessary resources that they need to be safe, fed, and sheltered. Meanwhile, another group’s conversation centers around a single-parent household with four children, very little income, and no family nearby to offer support.

In considering different people’s points of view, it is essential for students to engage in perspective taking so that their solution is representative of the broadest set of the public’s needs possible. This governing commitment points them toward ethical conduct for the greatest good.

Through this work, students build their relationship skills and self-management, the ability to manage their thoughts, emotions, and behavior effectively. They actively listen to their peers and demonstrate cultural humility. When a conflict arises, they not only work on resolving it constructively but also practice self-discipline. By practicing these skills, students act as leaders who are mindful of divergent and diverse perspectives, keeping equity at the forefront of decision making.

3. Analyze research to design and test solutions. This begins with students carefully comparing the pros and cons of the solutions they came up with for the people impacted. As students narrow down their thinking toward a single solution, they critically examine the evidence-based reasons in their thinking and approach the decision with fairness and justice. Along this line, students should take care to factor in the mission, vision, and values of the groups they plan to serve.

Once a solution has been decided upon, creating a prototype is essential to test it out. This can be done in a cost-effective and sustainable manner through community or parent donations, upcycling, or digital formats. As students collaborate, again reinforce the norm of allowing multiple viewpoints to strengthen the model or prototype. Such open communication will permit new iterations of the prototype to emerge and improve its overall quality. Groups should finalize their design by considering whether all group members have an identifiable contribution to the final solution and are satisfied with it.

The SEL competency of responsible decision making includes “learning to make a reasoned judgment after analyzing information, data, and facts” and “anticipating and evaluating the consequences of one’s actions”—and this is exactly what students do in this step. The groups will test out their prototype to gather feedback from the people impacted to see how the solution meets their specific needs. They will then use this feedback to make adjustments to their design in the fourth step.

4. Evaluate and iterate for an ethically justifiable solution. “Will this greenhouse design work in different parts of the world?” asks Shaniqua in the New Jersey classroom. The opportunity for students to revisit and revise their initial solution is an essential component in ethical problem solving.

Student-created greenhouse made with recycled materials

© Karen Cotter

Student-created greenhouse made with recycled materials

© Karen Cotter

As students reconsider their initial design in light of further evidence or arguments, the group should consider ways to respectfully challenge and resolve disputes. For example, Prince believes that his design is the best for any area of the globe, but no one listens to his input.

As educators, we can use an opportunity like Prince’s input being overlooked to cultivate students’ relationship skills and responsible decision making. This step requires students to work on developing empathy and gaining an appreciation for the feelings and viewpoints of others. They learn that throughout the design process, they are bound to encounter conflicts, and resolving them effectively requires that they actively listen, are open-minded to the ideas and needs of others, and embrace the iterative nature of the process.

This step also emphasizes responsible decision making, which, when used purposefully, can help students to look beyond their own needs to the greater good. The argumentative reasoning of this phase demands students’ thoughtful care and stewardship of all people affected, with an ethical lens. According to medical ethicists, decisions should be made on the basis of sound reasoning (i.e., evidence, principles, arguments) that “fair-minded” people can agree are relevant under the circumstances. Evidence-based reasoning ensures that the most ethical and justifiable solutions can be achieved under the circumstances and constraints.

5. Communicate findings to all relevant stakeholders. Sharing out the students’ findings with an authentic audience is essential to making the project genuine. Taking public action in sharing their discoveries or design is a critical lever in an ethical framework. Students gear up to practice the skill of self-management, as well as setting personal and collective goals.

N’azir is scrolling through her Instagram feed to look for other global users who are passionate about climate change.

N’azir is scrolling through her Instagram feed to look for other global users who are passionate about climate change.

In New Jersey, students in their teams have already discussed how they will communicate their greenhouse design and organized their presentation; they have engaged the SEL skills of self-discipline and self-motivation. Acknowledging different cultural and group norms for communication is also essential and most effective in reaching the intended audience when sharing the results.

As your students share their findings with the world, emphasize how their decision-making process created an opportunity to serve the public good. By making their results public, and sharing their rationale and evidence, their ethical conduct can spur additional research and action. In essence, the experience underscores how sharing scientific thinking for the public interest and public consumption can further scientific development.

This ethical framework guides students to think beyond themselves to identify solutions that impact their community. The added SEL benefits of self-reflection, social awareness, relationship skills, and appreciation of the world around them awaken students’ consciousness of core ethical values, equipping them to make decisions for the greater good. Using prosocial science topics like climate change empowers students to engage in relevant, real-world content to create a more equitable, sustainable, and just world where they experience how their humanity can impact the greater good.

Comments