54,000 students have registered for the Fall 2015 run of the Greater Good Science Center’s free online course, “The Science of Happiness”; roughly 10,000 responded to a survey we gave them measuring their health, well-being, and personal life circumstances before the start of the course. From looking at the responses, we found four distinct happiness patterns among the students.

1. Loneliness and stress hurt well-being

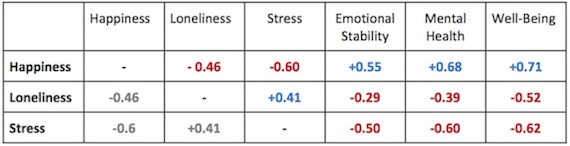

It should come as no surprise that happier people tended to be less lonely and stressed—or that less lonely and stressed people tended to be happier. According to our measures happier people were also more emotionally stable, and enjoyed better self-reported mental health.

For the data nerds, the table below shows statistically significant correlation, or “r” values, representing the strength and direction of the relationship between values, for several of the measures included in the pre-course survey.

Correlation table showing strong positive (+, blue; the metrics go in the same direction) and negative (-, red; the metrics go in the opposite direction) relationships between several measures included in the Pre-Course Survey for GG101x: The Science of Happiness

Correlation table showing strong positive (+, blue; the metrics go in the same direction) and negative (-, red; the metrics go in the opposite direction) relationships between several measures included in the Pre-Course Survey for GG101x: The Science of HappinessThis pattern is consistent with two key ideas that we cover in The Science of Happiness:

- Being able to experience a full range of emotions, including lots of positive and pro-social states like amusement and love, while not getting tangled up in distress and anger—that is, maintaining emotional stability—is good for happiness; and

- Feeling connected to others—that is, not lonely—is good for happiness. For those of you who suspect you might be on the low end of happy and emotionally stable, or high in loneliness and stress, data from our previous course suggests that sticking with the course and trying the Happiness Practices in earnest is a promising route to improving your happiness levels.

2. People in romantic relationships are happier than singles

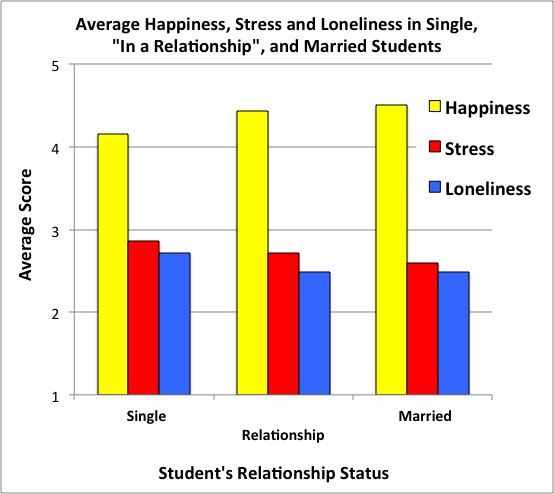

Consistent with our previous analyses of student responses, people in romantic relationships reported greater happiness, lower stress, and less loneliness than singles, as shown in the following graph.

On average, students who described themselves as single also reported lower happiness and higher stress and loneliness than students who indicated being “in a relationship” or married.

On average, students who described themselves as single also reported lower happiness and higher stress and loneliness than students who indicated being “in a relationship” or married.Further, the type of romantic relationship appeared to make a difference: Married people were slightly happier, less stressed, and less lonely than those in a relationship but not married. This suggests—in agreement with the scientific literature—that social connections, sometimes in the form of committed romantic relationships, factor into happiness.

3. Happiness increases with age

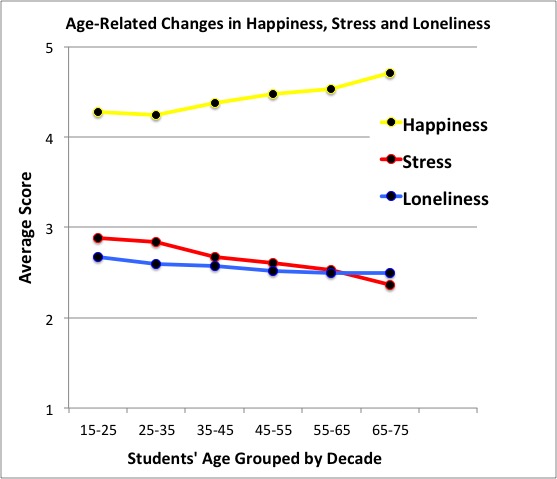

Since this course has such a wide age range, we were interested in whether and how age factors into happiness. Does happiness diminish with age, as the very profitable anti-aging cosmetic industry might have us believe? Our data suggest not.

Measured cross-sectionally between 15 and 75 years old and grouped by decade, students’ age in years was associated with increasing happiness and a steady decline in loneliness and stress.

Measured cross-sectionally between 15 and 75 years old and grouped by decade, students’ age in years was associated with increasing happiness and a steady decline in loneliness and stress.

Contrary to the archetypal human quest for a fountain of youth and consistent with other scientific insights about aging and well-being, our older students were systematically happier, less stressed, and less lonely than our younger students.

4. Which countries are happiest?

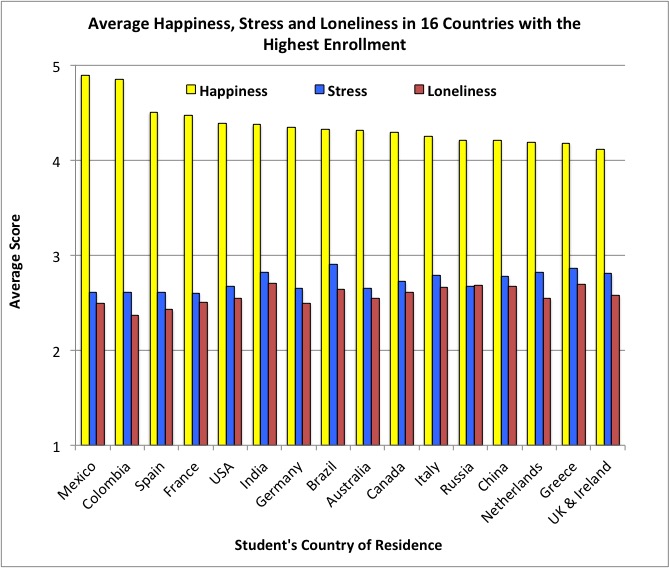

Finally, we looked at how people from different parts of the world were doing in terms of happiness, loneliness, and stress before starting the course. Amongst students who completed the survey, those from Mexico and Colombia were happiest—happier than the 13 other nationalities with enough students for a valid measurement. Though the differences are slight, the overall pattern in the data suggests that in places where happiness scores are higher, loneliness and stress scores are lower, and, in turn, when loneliness and stress go up, happiness goes down.

Plotted from highest to lowest happiness left to right, average happiness, stress and loneliness scores amongst students from the 16 countries with the greatest number of registered students show that around the world, higher happiness is associated with lower stress and loneliness, and vice versa.

Plotted from highest to lowest happiness left to right, average happiness, stress and loneliness scores amongst students from the 16 countries with the greatest number of registered students show that around the world, higher happiness is associated with lower stress and loneliness, and vice versa. Taken together, these data suggest that social connection is the key to happiness. On the starting block of The Science of Happiness, students with strong, close connections tend to be happier. Will the knowledge and activities of the course help others increase their happiness? We will continue to share insights as we discover them. After the course is finished, we’ll be able to compare this survey to the post-course survey. This will tell us if The Science of Happiness increased anyone’s happiness. We’ll also discover what kinds of course activities seemed to help the most!

Comments