Have you ever hated your partner?

You are not alone: It turns out that almost all of us have times when we strongly dislike the people we love the most—although some of us may not even realize it.

In a series of studies, Vivian Zayas and Yuichi Shoda found that people don’t just love or hate significant others. They love and hate them—and that’s normal. The key to getting through the inevitable hard times, as my own research suggests, is to never stop trying to understand where your partner is coming from.

Love is complicated, isn’t it?

How did Zayas and Shoda find the hate in the midst of love? They asked study participants to think of a significant other they like very much. Then, the participants reported on their positive and negative feelings toward that person. Unsurprisingly, people reported highly positive feelings and very low negative feelings toward the person they had chosen.

But then the researchers assessed implicit feelings—the emotions they might not be consciously aware of—about the significant other. How? Participants did a standard computer task that measures how quickly they respond to certain directions. They’d see the name of their significant other pop up on the computer screen, which was then was quickly followed by a target word that was either positive (e.g., lucky, kitten) or negative (e.g., garbage, cancer). Their job was to categorize the target words as positive or negative as quickly as possible by pushing the correct button.

That’s when the bad feelings came out.

Here’s how our brains work, as revealed by decades of psychological research: If we are thinking about something pleasant when a positive word pops up, we are quicker to categorize it as positive; but when a negative word pops up, we are slower to put it in the negative category. Likewise, if we are thinking about something unpleasant, we will be slower to categorize positive words and quicker for negative ones.

This task allows researchers to actually quantify people’s feelings towards their significant others, by calculating how quickly they respond to positive words and negative words after seeing their significant other’s name.

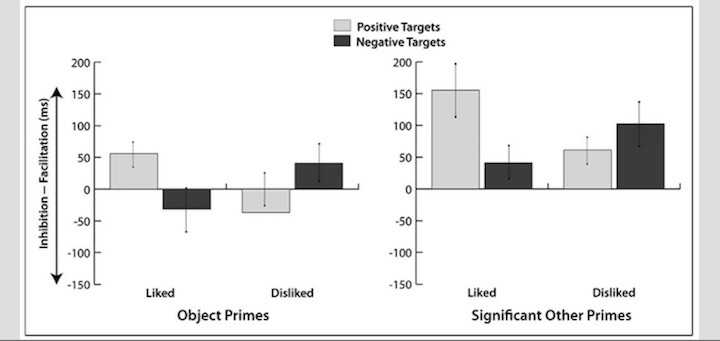

Still with me? Great, because here is where it gets interesting. Take a look at the graph below. The bars on the right show that, as expected, participants were quicker to categorize positive words after seeing their significant other’s name. But they were also quicker to categorize negative words. Not just not slower—actually quicker!

Zayas & Shoda (2015)

Zayas & Shoda (2015)The effect for positive words was larger, but there was a small effect showing that thinking about their significant others actually boosted people’s responses when categorizing negative words like garbage and cancer. These were significant others toward whom participants reported feeling very positively and not very negatively, yet these findings show that at an implicit level, people hold both positive and negative feelings toward the ones they love.

(Note: The bars on the left side of the graph show the typical response using positive and negative objects, such as sunsets and spiders, where positive objects only affect positive target words and negative objects only affect negative target words.)

Thus, people feel both positively and negatively toward those they love. This may not surprise you. Those closest to us, such as our romantic partners, invoke strong feelings on both ends of the spectrum—some days, thoughts of our romantic partners may leave us awash with love and admiration; other days, we may feel dislike or even repulsion.

It’s a thin line

What these findings suggest to me is that this love/hate dynamic is a normal part of close relationships. Feeling negatively towards your partner does not mean that you are doing something wrong or that you are in the wrong relationship. It seems hating your partner in the moment does not mean that you don’t also love them a lot—which is actually a bit of a revelation (and a relief).

Why does this study matter? Much of our relationship rhetoric focuses on positive and negative as two ends of a spectrum—feeling more positively toward your partner means you feel less negatively toward them, and vice versa.

While that may be true in one particular moment, it isn’t representative of the complex nature of your relationship overall—or even in one day! Our feelings toward our partners can range wildly from moment to moment—and it seems that may just be part of the wild ride of sharing your life with another complex human being. So, despite the overwhelmingly positive pictures posted on social media of all your friends’ happy relationships, know that you’re only seeing, at best, half the story.

There’s another finding worth highlighting from the Zayas and Shoda study. They also looked at people’s implicit feelings toward significant others that they reported disliking a lot. These were disliked people who played an important role in their life, such as exes or estranged parents.

When shown these significant others’ names, people were quicker to categorize negative words, as expected. But they were also quicker to categorize positive words, suggesting that feelings toward loathed significant others aren’t so set in stone either. Instead, it seems we hold some positive views of these significant others, even as we profess our dislike of them—even if we may not be able to admit it at a conscious level.

Not all bad feeling is bad for you

Of course, there is such a thing as too much hate. Relationships don’t need to be all positive all the time to be happy and healthy, but having too much negativity can be harmful. Instead, the key seems to be having a high enough ratio of positive to negative experiences.

Researcher John Gottman found that stable, happy couples had about five times more positivity than negativity during conflict conversations. On the other hand, couples who were heading towards divorce had a ratio more like 0.8:1. That is, way more negative than positive. While some negative emotions should be avoided at all costs, other negative emotions—such as guilt or sadness—when experienced in the appropriate setting, may be adaptive and help us change for the better.

For example, feeling guilty when you’ve done something wrong can help you correct your behavior in the future and make the proper amends. Feeling sad about growing apart from a good friend may help you realize you still care about that relationship. In relationships, conflict can help you negate bad patterns and work through issues.

In addition, it seems to me that the good is not as good if you aren’t occasionally contrasting it with something bad. We need some emotional variety—feeling good all the time might just get boring! Moreover, people who are forcing themselves to feel positively all the time when it isn’t genuine may not reap the same benefits as those who are experiencing genuine positive emotions.

Seven ways to make love stronger than hate

So how do you keep that love/hate ratio positive? The key is understanding—as opposed to avoiding conflict or suppressing bad feelings that are perfectly normal.

Along with my colleague Serena Chen, I ran seven different studies of couples, conflict, and relationship satisfaction. And I found in all of those studies that people felt less satisfied when they didn’t feel understood after conflicts with their partner. But when they came out of conflict feeling understood, there was no negative impact on relationship satisfaction.

We got these results in a number of different ways. People who reported fighting frequently—but who at the same time felt understood by their partners—were no less satisfied with their relationships than people who rarely fight. People who remembered a past conflict in which they felt understood were no less satisfied than those in a control group; those who did not feel understood showed negative effects. People who reported on their conflicts every day for two weeks were equally satisfied on both days when they fought and days when they didn’t—if they felt understood.

In our laboratory study, couples talked about a source of conflict in their relationship. People who felt understood during the conflict conversation felt more satisfied after the discussion than when they’d first arrived in the lab. If they didn’t feel understood, they were less satisfied.

In other words, relationships can survive conflict and bad feelings if partners never stop feeling seen by the other.

Is it just that people are better able to find a solution to their problem if they understand each other? Understanding does aid in conflict resolution, but it turns out that understanding can even help those fights that will never be resolved. Those issues may stem from political, religious, or personality differences, or maybe just different movie preferences.

Whatever their source, understanding can help for those fights, too. In fact, understanding may be most important when you face issues that cannot be easily resolved, such as different religious or political views. In these situations, understanding allows you to “agree to disagree” when no amount of fighting is going to change your minds.

What is it about feeling understood that helps alleviate those negative feelings that typically arise after conflict? We found that when you feel understood, it signals to you that your partner cares about you and is invested in the relationship. It also makes you feel like your relationship is strong and worth fighting for. And in the end, feeling understood, especially when your partner has a different opinion than you, just feels good, plain and simple.

So how do you increase understanding during conflict? Here are seven suggestions for how to think and act to do so.

- Instead of asserting your own point of view, try to take your partner’s perspective. Make it your goal to understand why your partner feels the way they do.

- Avoid the four horsemen of the apocalypse—criticism, defensiveness, contempt, and stonewalling.

- Give your partner the benefit of the doubt. Assume that their intentions are not malicious.

- Take a moment to reflect on your partner’s positive traits. You can even try some gratitude-inducing techniques.

- Think of you and your partner as a team, rather than opponents. Your goal is to figure out together why you do not see eye-to-eye and find a solution; it is not to win the fight and prove your partner wrong.

- Recognize that it won’t always be easy to follow these suggestions, especially if your partner isn’t playing by the same rules.

- Give yourself a mantra to repeat when you start feeling angry to help you remember your goal—even something as simple as “be understanding.”

This article was revised and synthesized from several pieces originally published on Amie Gordon’s Psychology Today blog.

Comments