Years ago, I went to work for a women-owned and women-led company, whose employees were composed of 80-90% white women. It had a fantastic culture that was all about trust and high expectations, one of the best I had ever seen as a consultant on organizational culture.

And then in 2020, George Floyd was murdered by police in Minneapolis. That event triggered global protests over racism and police brutality. And like many other companies at that time, mine had a reckoning. The CEO made herself extremely vulnerable, crying in front of the whole company, saying, “We are going to become an anti-racist company.” I was moved, and I volunteered to help her realize that dream.

The company made real progress in the two years after George Floyd’s murder, hiring dozens of people of color and shifting its demographics. But as time passed, those same employees confided in me: They were being interrupted in meetings, their expertise questioned, and promotions passed over in favor of less-qualified white colleagues. The “diversity” remained all at the bottom of the organization.

After a group of us started meeting to highlight some diversity, equity, and inclusion actions we could take, the CEO heard about our meetings. Three of the four members of our group were fired immediately, under the guise of budget concerns. Two of the members of the group had just been promoted to leadership positions a few weeks prior to the firing.

As I hope this anecdote illustrates, good intentions don’t necessarily lead to the desired results. Why have so many diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) processes failed? During a time when the very idea of DEI is under attack by the federal government, how can we keep learning and growing? It turns out that the research does point to positive recommendations, techniques, and approaches we can salvage from decades of failures like the one I witnessed. But we also need to ask ourselves if maybe DEI should go into the dustbin of history, to be replaced by something better.

50 years of failed DEI programs

Diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives started during the Civil Rights Era in the 1960s and emphasize the needs and contributions of people with various identities. Why was that important?

Because even in the 1960s, the United States of America was a very diverse place. Today, according to the World Population Review, the U.S. is one of the most ethnically diverse nations on the planet, with over 40% of the U.S. population identifying as non-white or multiracial and with more than 350 languages spoken in American homes. “Diversity” is not something we should be “for” or “against.” Diversity is just a plain and simple fact, in the U.S. and around the world. By most estimates, people of European descent will become a minority in the United States by 2050.

Before we jump into failures of the DEI industrial complex, let’s be clear that evidence for the benefits of diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging are strong. At the Greater Good Science Center, we’ve already reported that diverse social connections help build your success and happiness, being around diverse people can make us more creative and diligent, and diversity can be good for the bottom line. Yet we also know that diversity without inclusion can have deleterious effects on creativity.

So we already know “why” DEI can be helpful. The question is: “How” should we encourage DEI in workplaces? Unfortunately, the last 50 years of DEI programs have yielded many more failures than results. DEI programs—mainly trainings and workshops—have tried to help Americans live with that fact and indeed thrive in a diverse world. But I’ve been facilitating “diversity” or “DEI” or “DEIB” workshops for 27 years, and I have to tell you that, unfortunately, I don’t think these kind of workshops have made much of a difference—and may even cause harm to employees of color.

In her new book Who Pays for Diversity?, Oneya Fennell Okuwobi outlines how many diversity programs have commodified and tokenized the people they’re meant to elevate. “The employees I spoke with saw diversity initiatives, even at their best, as ‘smoke and mirrors,’ both showy and ineffective,” she writes. The programs can put extraordinary demands on those employees as they’re asked to step into many roles in order to showcase the company’s “diversity.” She goes on to say, “What if we downplay the negative effects of diversity just because of the promise that it could work?”

Harvard University’s Frank Dobbin and Alexandra Kalev found that over the last 30 years across thousands of companies, most diversity training yielded little to no effect on bias and in some cases actually increased bias. They found that there were a few key reasons for the lack of efficacy in DEI trainings:

- Short-term training doesn’t change behavior;

- Training can reinforce stereotypes;

- Training can lead to false confidence in anti-discrimination efforts (e.g., after completing DEI training, employees may believe their workplace has already “fixed” discrimination issues, which can lead to complacency);

- Mandatory training can breed resistance and backlash among white employees (by making them feel excluded, targeted, or controlled).

Indeed, hundreds of studies since the 1930s find that anti-bias training does not significantly reduce prejudice or improve workplace diversity. While a meta-analysis of 65 DEI studies does show some knowledge and skills-based changes as a result of diversity training, programs were less effective in changing deep-seated biases and attitudes.

With millions of dollars invested into training, we are still not seeing significant results where it matters. Helping people grow their knowledge and skills is one thing, but it doesn’t get us all the way to hard outcomes like reducing discrimination in hiring and promotion or experiential outcomes like inclusion, belonging, and reduced microaggressions (a term for intentional or unintentional verbal and behavioral slights based on group membership, such as not inviting certain colleagues to lunch or speaking of them in a patronizing way). This statistic knocked me off my feet when I read it: Between 1985 and 2016, the percentage of Black men in management positions within organizations over 100 people barely budged from 3% to 3.2% over the course of those 30 years!

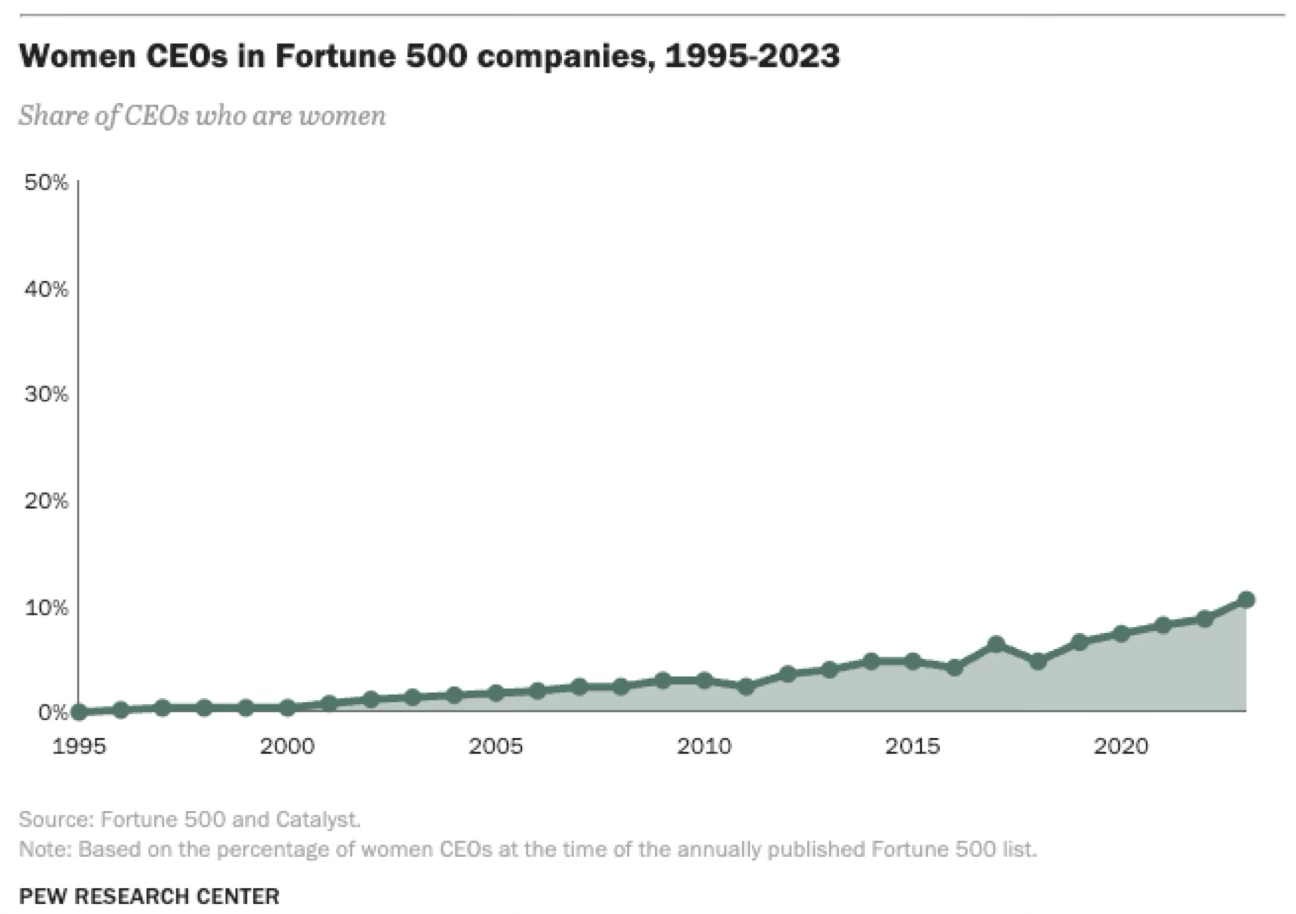

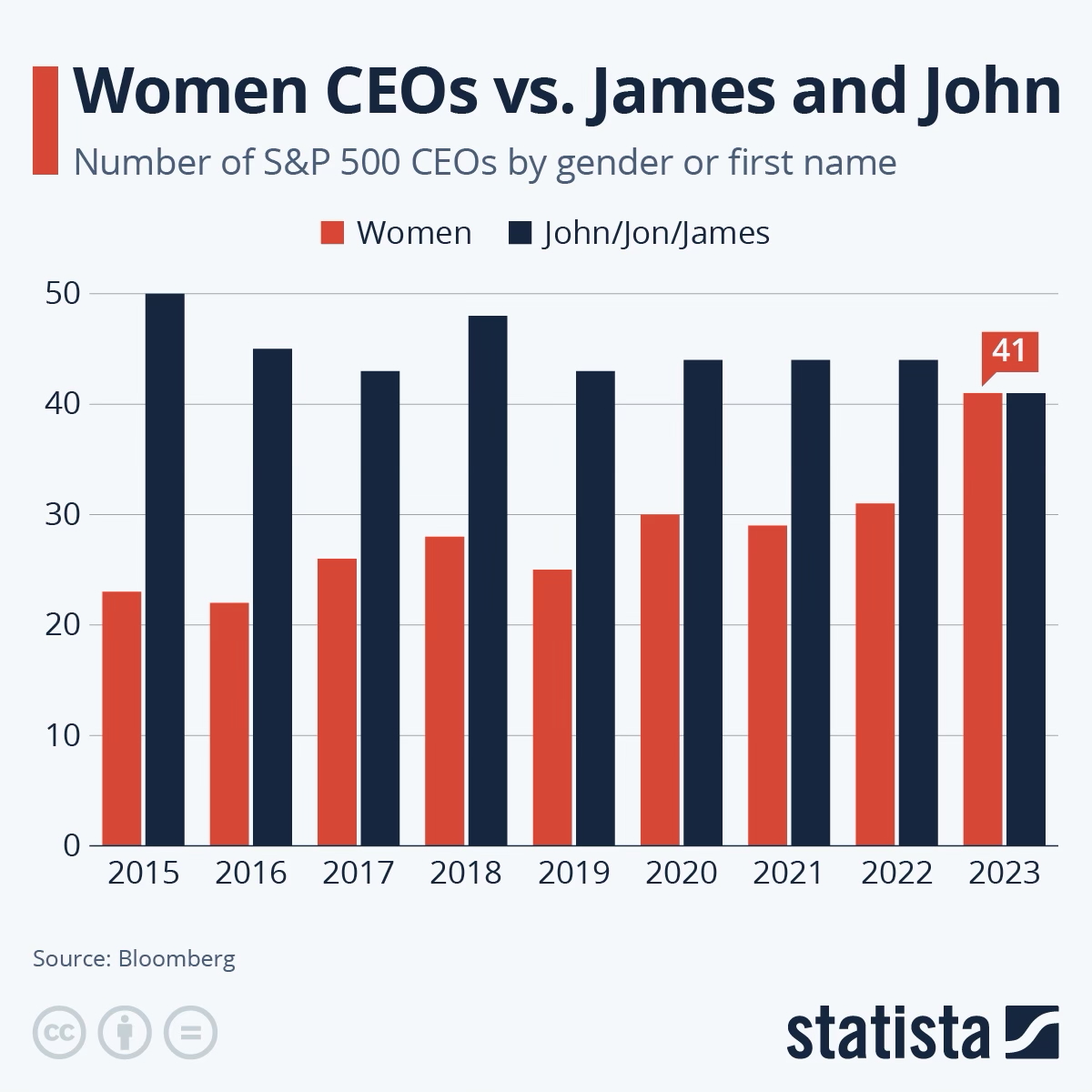

Things don’t fare that well for women in leadership either. As you can see below, the share of female CEOs has been creeping up ever so slightly over the years, and only in 2023 did the number of female CEOs finally surpass the number of CEOs named “John” or “James.”

The inequalities don’t end with race and gender. For lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ+) workers, we’ve still got work to do. A 2023 study by the Williams Institute found that 17% of LGBTQ+ workers reported workplace discrimination or harassment in the past year, with transgender and nonbinary individuals more than twice as likely to experience such treatment compared to their cisgender peers.

Disabled people face many challenges in the workplace. While the Americans With Disabilities Act has yielded quite a few gains, people with disabilities are unemployed at twice the rate of abled people and still face significant barriers in the workplace.

In short, my experience with that woman-led company was not unique. Overall, our strategies for realizing discrimination-free, diverse, equitable, and inclusive workplaces that work well for everyone have not worked very well. We’ve got to come up with a better “how” for DEI.

So what do we do about it?

We know that just throwing workshops at the problem isn’t going to solve all of these issues. So, does that mean we should take an axe to all DEI workshops and programs and even expunge the acronym “DEI” from all government programs, as the Trump administration has done? Perhaps we just haven’t got the “how” of DEI right.

In a systematic review of all the major DEI training or anti-racism workshops studied between 2000 and 2022, a team at Boston University laid out three key recommendations for doing DEI work:

- Shift from one-time training to long-term, continuous programs;

- Focus on structural/organizational change, not just awareness;

- Use standardized metrics to measure long-term effectiveness.

What might these recommendations look like in the real world? “Long-term, continuous programs” (as opposed to a one-time workshop on, say, unconscious bias) could consist of a series of skill-building workshops on how to be an “upstander” instead of a bystander when you witness workplace microaggressions. In these workshops, for example, participants might practice different ways to respectfully speak up for women whose ideas are getting co-opted in meetings.

Focusing on “structural/organizational change” might look like implementing a set of rubrics for job interviews and promotion pathways, so that each candidate gets reviewed against a fair and standard set of criteria, rather than the unconscious feeling of whether or not you’d “like to have a beer with the candidate” because they come from a similar background to you. While we can never remove bias totally from the system, these structural changes make it more likely that we have fairly equal hiring and promotion rates for all people.

Using “standardized metrics to measure long-term effectiveness” might look like really pinpointing the areas an organization might want to see change. For example, perhaps the company markets their products to women or a diverse range of ethnicities but has very low rates of gender or ethnic diversity among their leadership ranks. Perhaps a structured leadership and mentorship program that helps more marginalized people move into leadership could help, especially if there are standard metrics done before and after the program has had a chance to make an impact.

A way forward

Organizational consultant and author Lily Zheng is, in my view, one of the most important voices on DEI in the United States. In their important piece, “What Comes After DEI,” they proposed a new framework to replace DEI. Zheng calls it FAIR, which stands for:

- Fairness: when all people are set up for success and protected against discrimination.

- Access: when all people can fully participate in a product, service, experience, or physical environment.

- Inclusion: when all people feel respected, valued, and safe for who they are.

- Representation: when all people feel their needs are advocated for by those who represent them.

Though Zheng’s ideas are too new to have been scientifically tested, they’re worth considering. As I read Zheng’s fantastic article, I was cheering inside, because their focus on win-win, data-driven, structural, and outcome-based solutions that improve working conditions and organizational cultures for everyone makes absolute sense to me.

The only thing I would add to Zheng’s treatise is that this work takes significant effort, and we need to be grounded in a clear “why” for doing this work.

Our “why” for DEI has shifted throughout the decades. Are we doing DEI because we don’t want to get sued for discrimination (1970s–1980s)? Are we doing it because it’s the “right” thing to do morally (1990s–2000s)? Or is our “why” about “the business case for diversity” (2010s–)?

I believe that the “DEI why,” or rather, the “FAIR why,” is different for every organization. Every organization should begin with clarifying their strategy for “winning” as an organization. Then they should define the behaviors or culture that helps them deliver on that strategy. And finally they should identify how FAIR helps them win.

What naturally follows is that many of the FAIR activities ultimately help them deliver on their strategy for success (whether it’s competing on innovation, price, customer service, or some other metric that matters).

Strangely, I feel a deep sense of sadness and empathy for the CEO who fired me. She did not create the 400 years of racism, discrimination, and bias that preceded her. Yet despite her view of herself as a progressive woman, she did fall prey to it. She felt threatened and protective of the organization she built from the ground up. Perhaps decades of media bias and the programming of her parents crept into her subconscious fear of “the other.”

But, if she had taken the time to listen to our DEI ideas and recommendations, perhaps we would have seen more growth and better results for the organization, more structural changes that led to marginalized people moving into leadership roles, a thriving DEI consulting practice, and a genuine example of what a truly healthy, diverse, equitable, and inclusive organizational culture looks like.

Could the DEI industrial complex be (inadvertently or otherwise) feeding the us-vs.-them dynamic I saw emerge at that company? Maybe; my own opinion is yes, definitely. I recently heard john a. powell from the Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley talk about his new book, The Power of Bridging. He said something that really stuck with me: “We need a new story…a story of us.” I think that’s absolutely right. If we want real change, we need more than workshops—we need structural changes that build fairness, equity, inclusion, and the fullness of the diversity of experiences into the very fabric of our organizations in a way that benefits everyone.

We need a new story of us.

Comments