If you practice meditation, you probably spend a lot of time training your focus—on the breath, the body, or your wandering thoughts and feelings. But if you only train focus, you may be missing out on some profound benefits.

Another valuable skill is called open awareness, where we simply rest in the awareness of awareness, feeling what it’s like to be conscious without paying attention to anything in particular. In everyday life, open awareness means approaching situations with fresh eyes, letting go of our habitual reactions and our expectations for the future.

Credit: Maddie Siegel

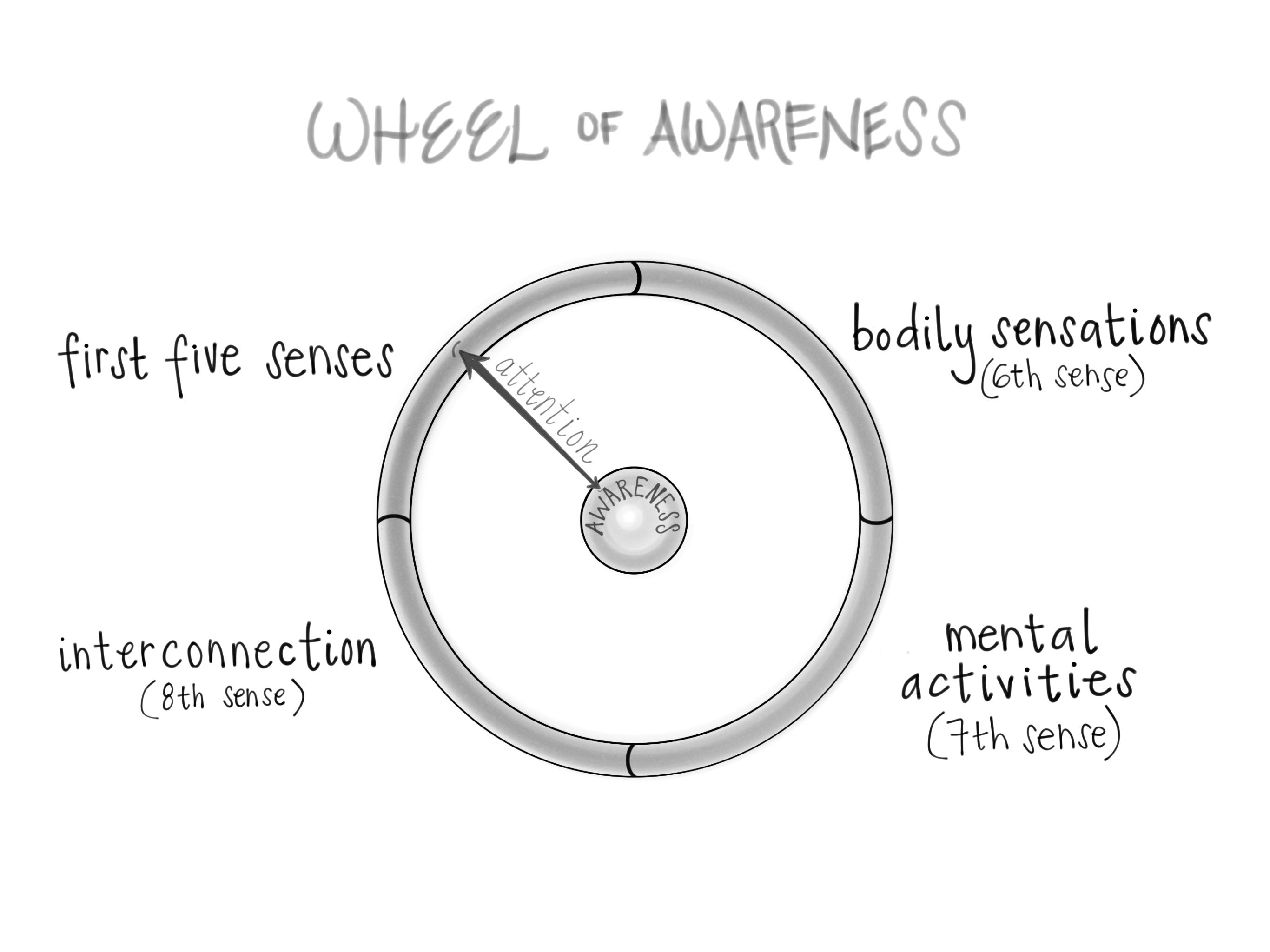

Credit: Maddie SiegelOpen awareness is part of the Wheel of Awareness practice, a meditation tool I’ve developed over many years and offered to thousands of individuals around the world. In the Wheel, we imagine awareness lying at the center of a hub and sending out spokes of attention to points on the rim—focusing on our first five senses; the interior signals of the body, such as sensations from our muscles or lungs; the mental activities of feelings, thoughts, and memories; and finally our sense of connection to other people and to nature. To practice open awareness on the Wheel, we visualize bending the spoke of attention around so it aims back into the hub, retracting the spoke, or simply leaving it in the hub.

In my new book Aware, I offer a complete guide to the Wheel of Awareness and what may be happening in the brain when you practice it. While open awareness is one of the most advanced contemplative techniques, my research and clinical experience suggest that it has the potential to offer us more freedom, peace, and well-being in our lives.

The power of open awareness

Some people find that being aware of awareness is quite new. Some find it confusing, disorienting, difficult to hold on to. Some find it bizarre.

In one workshop, for example, a participant called this awareness-of-awareness experience “really odd.” When I asked what “odd” felt like, he said, “I mean, it was really weird.” So I asked him what “weird” felt like, and he said, “Just really strange.”

I gently suggested that he stop comparing it to other experiences, and instead simply describe the feeling. He was silent, and then he smiled. His expression glowed, and he said, “It was incredibly peaceful. It was so clear, so empty, yet so full. It was amazing.”

He was not alone. Others in that same group, and in workshops around the world, have come to say similar things. Here are some of the phrases that have been used to try to express what awareness of awareness feels like for them: “As wide as the sky.” “As deep as the ocean.” “Complete peace.” “Joy.” “Tranquility.” “Safety.” “Connection to the world.” “God.” “Love.” “At home in the universe.” “Timelessness.” “Expansive.” “Infinity.”

And the pattern keeps on emerging as people dive into the practice. One participant even handed me a note; it said she couldn’t openly state what happened in that step, which she experienced as “an amazing sense of expansiveness and peace, a feeling of wholeness I’ve never had before,” because she thought others would think she was bragging. One person said he felt so much love that he couldn’t share that experience for fear his professional colleagues in the seminar would consider him weak. Recently, I offered the Wheel practice to three thousand people in one room, and hundreds raised their hands when asked if they felt a sense of expansiveness or a loss of time. As I captured in a systematic survey, these descriptions share very similar themes of love, joy, and wide-open timelessness.

What is going on here? Why would these statements, though not expressed by all, be offered from such a disparate group of people from around the world?

To be clear, some participants have great difficulty with this step and don’t offer any descriptions, or simply say that their minds wandered, they felt confused, or they simply focused on the breath. Each time I do my regular Wheel practice myself, this hub-in-hub step feels subtly different. Sometimes a shift doesn’t even seem to happen and I am stuck on the rim, thinking of things I hope would happen, or being swept up by memories of past hub-in-hub practices and wishing those would occur again. If I expect things to go a certain way, they usually don’t.

According to journalist Daniel Goleman and neuroscientist Richard Davidson, the brains of longtime mindfulness practitioners look different when they are practicing open awareness meditation. Gamma waves—which, for most of us, occur briefly and in one spot of the brain—are elevated all across their brains, corresponding to the sense of vastness and spaciousness they feel. Neuropsychiatric researcher Judson Brewer and colleagues also found similar electrical patterns during a range of meditative practices that are called “effortless awareness”—a state of being aware of whatever arises as it arises.

Social neuroscientist Mary Helen Immordino-Yang has also found that these attentional states are associated with neural firing in primitive brain stem regions associated with the most basic life processes. This state of awe and gratitude, this joy for life, is an inner sense of vitality and a relational sense of connection to the larger world around us. We can propose that open awareness naturally gives rise to the subjective experience of joy, awe, and peace—of meaning, love, and connection.

How filters constrain us

My patient Mona was a forty-year-old mother of three children under the age of ten, who found herself often at the end of her rope. She was raising her children without much help from her spouse or family and friends, and was becoming easily irritated with them, and then irate with herself for feeling this way. She had frequent experiences of shutting down and distancing herself from her children, and chaotic outbursts of sadness and anger.

This essay is adapted from Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence—The Groundbreaking Meditation Practice (TarcherPerigee, 2018, 400 pages).

This essay is adapted from Aware: The Science and Practice of Presence—The Groundbreaking Meditation Practice (TarcherPerigee, 2018, 400 pages).

Mona began to practice the Wheel of Awareness, and it enabled her to build the internal resources to become more present and aware. Practicing open awareness became a sanctuary of relief from her feelings of rage and burnout. It became easier for her to witness her children’s behavior and experiences, and see new options for how to respond.

Why is open awareness so powerful? Without it, we typically see the world through a set of filters that can constrain our experience and keep us stuck in painful patterns of emotion.

Neuroscientists commonly call the brain an “anticipation machine.” To predict and get ready for what is going to happen next, it constructs a perceptual filter that selects and organizes what we actually become aware of based on what we’ve experienced before. Filters shape what we focus on, which in turn influences the information our brains receive. And filters help us survive: If we are driving a car, we need to be scanning the road ahead for obstacles and primed to step on the brakes rapidly, filtering our options to a select few so that we can react quickly when needed.

Filters help us make sense of life and feel safe and secure in an often confusing, unpredictable world. As the military and other organizations like to say, we live in a time of “VUCA”—volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. In this challenging moment in human history, certain people may be hardening their filters unconsciously in an attempt to make the world seem more predictable and less threatening—one potential way of understanding today’s extreme worldviews and sharp political divisions.

And filters continually reinforce themselves, giving us the appearance that what we perceive through them is accurate and complete. We might even see this as the basis of confirmation bias, where we selectively pay attention to evidence that conforms to our existing beliefs. We do not have immaculate perception; we perceive what we already believe.

Our human journey itself may be vulnerable to the development of rigid filters. Once we are adults and perhaps even before, during adolescence or late childhood, we’ve developed certain filters around our sense of self. They come from trying to fit into our social worlds, and trying to make sense of our personal experiences. Our top-down filters tell us who we are and what our personality is, how we typically behave, and what kind of future is open to us.

This may be why, as we move into adolescence and beyond, life can become dulled. We begin to filter too much through the knowledge and skills acquired through prior learning and lose touch with the novelty of “beginner’s mind”—a mind that is open and eager, without preconceptions. The social psychologist Ellen Langer has revealed that being open to fresh distinctions is a source of well-being and vitality. In Langer’s work, appreciating novel distinctions enhances our health and our learning.

The downside of such a filtering of reality is that we become limited in what we experience. Rigid filters may make it challenging to be present in life. We judge people and events before we allow ourselves to even experience them openly. But often we’re not aware of our filters, and we don’t even inquire as to their existence or validity.

Major growth can occur when we cultivate open awareness and lose or loosen some of the filters that arise in our lives—whether those filters represent our expectations about the future, our biases about other people, or the limitations we place on ourselves. But how to do this?

One way, of course, is to cultivate access to our hub beneath the filters of our rim. But beyond that, we can also be playful and have a sense of humor about who we are. Laughter and humor are gateways to open awareness and connection with others. Jokes are funny because they move in an unexpected direction—not where our filters expected the punchline to go. For a brief moment, we’re wrestling with something we never saw coming. It feels as if top-down expectations are meeting bottom-up surprise.

In that way, humor actually opens us up to new learning and more openness. It likely enhances neuroplasticity as it promotes a receptive state and makes learning last longer as the brain may be more likely to grow new connections in that open state, and it builds trust and connection with others. Not bad for a good chuckle.

So this is your challenge: You can use your mind to shift the patterns in your relationships with others and in your brain. You are not a captive prisoner, even though your mental filters will tend to move you into old patterns. Getting lost in familiar places is a natural vulnerability we all have; using your mind and your capacity to be aware is how you can find your way. Patience and persistence will be your friends along this path to greater freedom.

Comments