Our world has become more urban, overscheduled, fast-paced, and alienating. There are alarming rates of anxiety and depression surging across the country. The Surgeon General of the United States has stated that declining mental health among our youth is the crisis of our time.

As a high school teacher at San Domenico School, a K–12 day and boarding school just north of San Francisco, I am committed to helping our students navigate this emotionally perilous landscape. From a lifetime of contemplative walks in nature, I know the experience can provide a transcendent perspective, mainly by feeling connected to something larger than the self.

That’s a feeling called “awe.” According to the psychologist Dacher Keltner, awe is the feeling we get in the presence of something profound and vast that transcends our current understanding of the world, like standing under old-growth redwoods, looking up at the Milky Way galaxy on a clear night, or marveling at the growth and development of a child. When people feel awe, words such as amazement, surprise, wonder, and transcendence are often used to describe the experience.

As Keltner’s research has suggested, not only does awe feel good, but it is also good for our well-being. A key influence of awe is that we feel a sense of connection to something larger than ourselves—and to other people. Awe encourages us to be more compassionate. It makes us happier and healthier. Awe sparks curiosity within us and helps orient us to what truly matters in our lives.

But I wasn’t sure if this next wave of digital natives would agree. So last academic year, I began taking my 10th-grade “Myth and Meaning” classes (which explore the sacred and meaning in world religions, nature, philosophy, and psychology) on Awe Walks to find out. I wanted to discover if this mindful immersion in nature would, in fact, cultivate awe in teenagers.

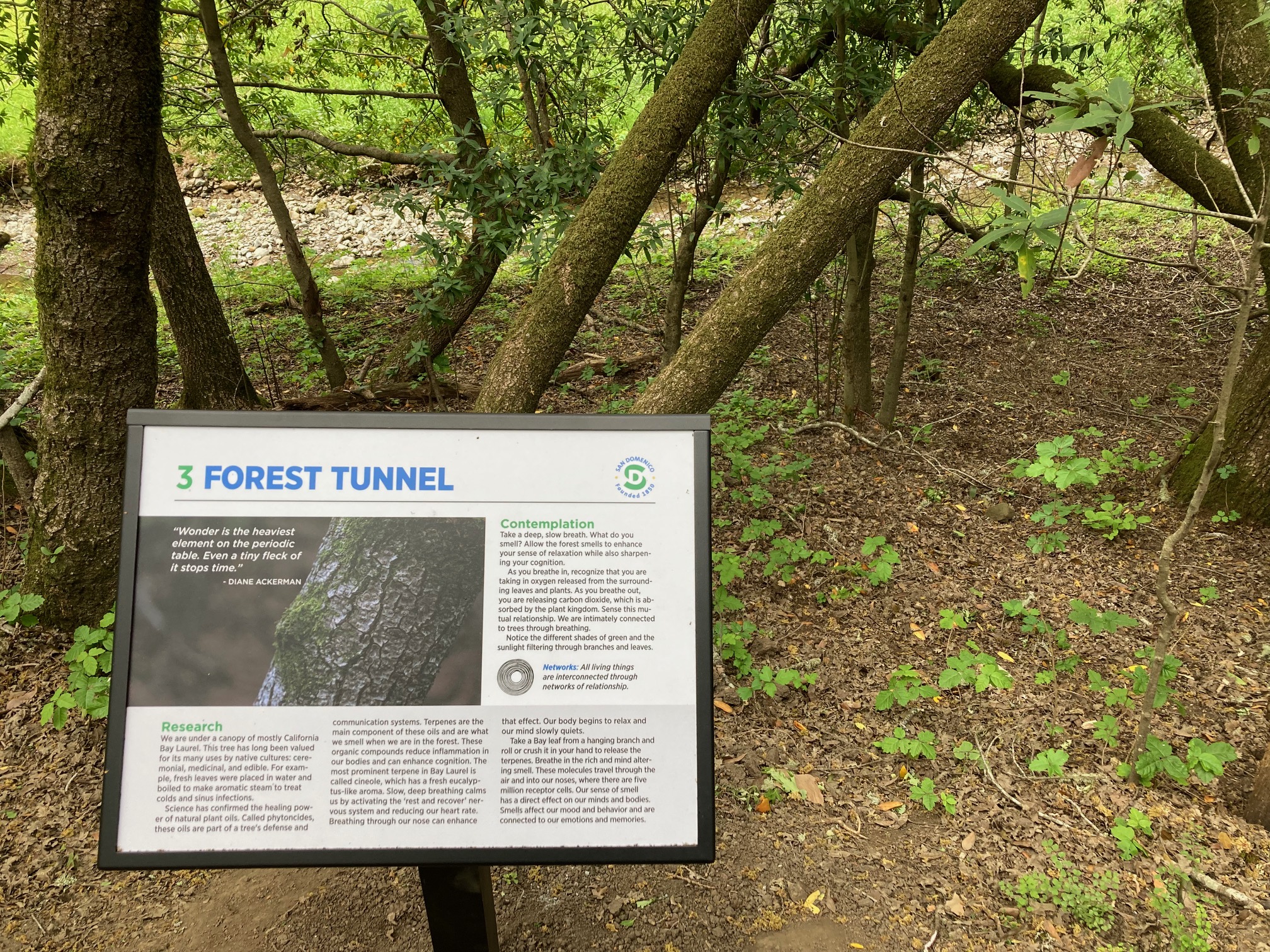

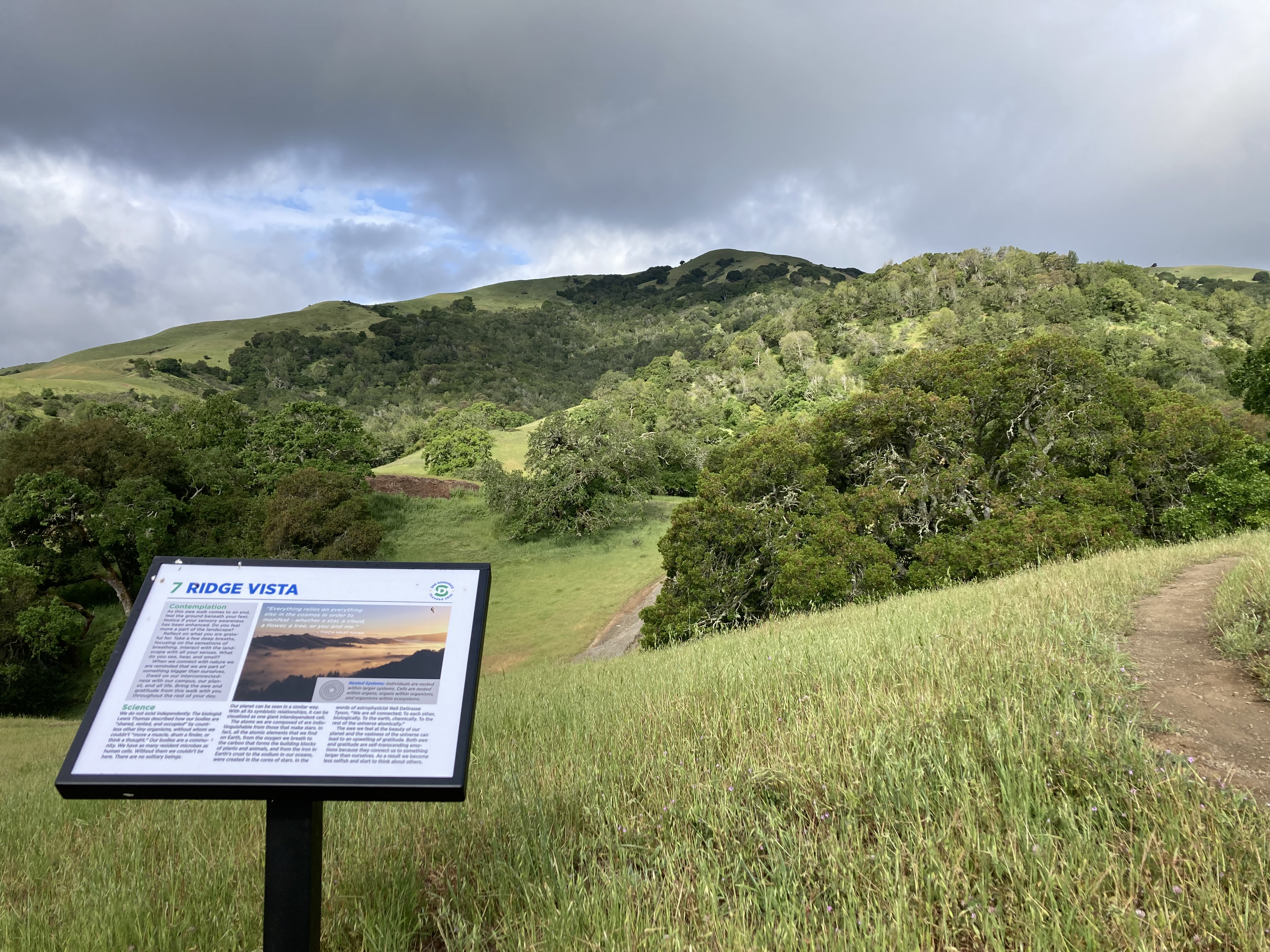

The walk is around three-quarters of a mile and has seven stations along the way. Each of the seven stations on the Awe Walk has a placard that combines photography, contemplative practices, ecological principles, and scientific research that aims to cultivate awe.

Over the course of nine months and four seasons, my students created Almanacs of Awe. These were books that combined photography with captions that convey where and why they felt awe or a gateway emotion of curiosity, wonder, or beauty.

For some students, it was the beauty of nature that captured their attention. A “butterfly’s many subtle colors were revealed the more I observed it,” wrote one student. “The stillness of the butterfly made me feel at peace.” For another, “seeing the way the water trickled and the way the light fractured and rippled on the rocks underneath amazed me. It felt like looking at art.” A humble pumpkin was a source of awe for a different student: “This pumpkin gave me awe because it is crazy to me how something so complex can be grown with just a seed, water, and sun. I loved the color of this pumpkin and the texture and little blemishes it had.”

Other students found a sense of perspective on these walks. “I felt awe when I went under this redwood tree and looked up at its branches,” wrote one. “In the moment I looked up at the tree, it seemed never ending. I think the tree had me in awe because it was so much larger than myself and gave me a sense of perspective.” Moss on a tree conveyed the power of humility to one student: “Moss on a tree. Simple, patient, and adorably soft and puffy. I personally love moss because of its simple, calm, and beautiful way of life. It inspires wonder in the way that it is so humble yet so powerful, an integral part of the ecosystem that doesn’t demand attention nor recognition for its contributions.”

As they amble along, students learn that simply being in nature can lower the stress hormones cortisol and adrenaline, and enhance the rest-and-recover nervous system, as research suggests. This walk fosters feeling connected to something larger than the self, which can be experienced in diverse ways. For some, the branching patterns of oak trees, combined with the luminosity of the sun, creates a sense of wonder and calm. Or students might notice the captivating designs of lichen and turkey tail mushrooms growing on a dead tree branch, sparking curiosity. The rich tapestry of nature provides endless variety and nuance to behold and explore across scales, from ridge lines, clouds, and sky to seeds, mosses, and leaves.

A clear blue sky offered a profound meditation for one student: “Often the sky is overlooked despite its constant presence in each of our lives. It is often not recognized for its simple beauty, but when looking up into a clear sky of pure blue, it is magnificent. It is a majestic curtain, a vast expanse of wonder waiting to be recognized and appreciated.”

Another student was reminded of the wonder that can be revealed by mindfully slowing down: “This stump stood out to me because of its perfect heart shape. On an ordinary walk, I probably would have failed to notice this natural wonder, which makes me sad to think about what other natural wonders I may have missed because I simply wasn’t looking.”

I was also inspired by many students who drew analogies or asked provocative questions from the phenomena they noticed on these walks. Tree roots offered a reflection on appearances: “The way these roots protruded from the ground caught my eye on our walk. I was reminded of a cave nestled deep in the woods. I think this shows us that what we see on the surface is never the entirety.” For another, an animal bone yielded existential insight: “The single bone on the forest floor tells a story about the life of an animal and its habitat. From life to death, it reminds us that we are all connected to that place we call home, bringing about a sense of peace and resolve.”

The interconnection of the forest provided wonderful questions about relationships: “The way the branches of another plant latch on to the tree shows how interconnected each living thing is and how we might help or harm one another. This scene makes me wonder: What am I connected to? What might I help or harm? These questions provoke a sense of wonder and curiosity about relationships.”

As the school year reached its conclusion back in June, my students and I reflected on our Awe Walks. The prevailing sentiment that emerged was these walks were meaningful because they allowed us to slow down, reflect, enjoy the moment, and refocus and reset. So much of school and modern life is about carrots and sticks. For many students, school feels like it is merely a means to an end. And this end, for our students, is likely college. This creates a K–12 system that feels like a protracted high-stakes entrance exam for college. This dynamic ratchets up stress, as extrinsic motivation eclipses intrinsic motivation. Against that landscape, it can be hard to find meaning, purpose, and awe.

These Awe Walks helped to create a greater sense of perspective by enabling a connection to something larger than themselves—nature, humanity, history, the planet, and the cosmos. This improved their emotional health and overall well-being through a slow and steady process of cultivating wonder, curiosity, gratitude, and awe about the world.

While San Domenico School is blessed with a remarkable campus that affords Awe Walks in nature, one doesn’t need acres of nature to seek awe. We can just as easily cultivate it in urban environments. The most important resource for discovering awe in any environment is an open and responsive mind. My students and I have learned that discovering awe is found by slowing down, paying attention, seeking novelty, fueling curiosity, and asking questions. It centers on how we are attending to the world. The quality of attention we bring creates a relationship with the world.

If our attention is reductionistic, fractured, means-to-end, bottom-line, transactional, then we will have that kind of relationship with the world. Awe points to another way. With a receptive mind, we feel awe in inspiring stories, music, art, science, parks, museums, neighborhoods, sports, history, and even countless YouTube videos. In other words: just about everywhere. The key to unlocking awe is knowing how to look. And how we look is how we live.

Comments