When he was just 13 years old, the parents of Matthew Boger threw him out of their home for being gay. While living on the streets of Hollywood, he was beaten in a back alley by a group of teen neo-Nazi skinheads, who’d picked him at random.

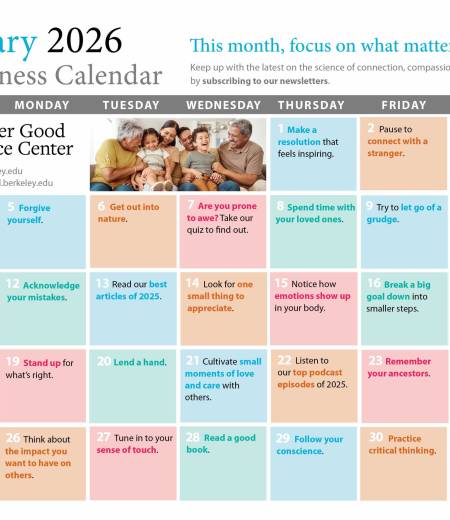

Matthew Boger (left) and Tim Zaal.

Matthew Boger (left) and Tim Zaal.

Boger survived both the attack and life on the streets. As the film Facing Fear recounts, Boger went on to become the manager of operations at the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles. One day, reformed neo-Nazi skinhead Tim Zaal came to speak at the museum.

The two men soon realized that they had met before: Zaal was one of the skinheads who’d nearly killed Boger 25 years earlier.

Jason Cohen directed the Academy-award-nominated documentary about Boger and Zaal’s journey to forgiveness and reconciliation. He, Boger, and Zaal recently came to Berkeley to show Facing Fear at Greater Good’s Summer Institute for Educators. Before the screening, I sat down with Cohen, Boger, and Zaal to discuss the film and their own stories of the power of forgiveness.

Jill Suttie: Jason, what made you want to tell this story?

Jason Cohen: It’s a sensational story that’s almost unbelievable when you read it. But then it felt like there was a lot to explore in the process of forgiveness that, at the point I met Tim and Matthew, they’d been going through for six years. The goal was to understand what they’d been through since they came back into each other’s lives, and what went into that.

Suttie: Why did you name the movie “Facing Fear?” What does fear have to do with forgiveness?

Matthew Boger

Matthew Boger

Cohen: We felt it was a metaphor. When a lot of people hear the title, they automatically think of Matthew and the fear he felt facing Tim, his attacker. But what we realized was that both of them had a lot of fears in coming to terms with this process of forgiveness. Tim will tell you that he also had plenty of fears in having Matthew back in his life, before they even thought of forgiveness.

Suttie: Sometimes people feel that forgiveness lets people off the hook. Have you seen that response from audiences?

Matthew Boger: I get that question a lot. People think that, if you’re forgiving, that somehow you’re saying to the perpetrator, “It’s OK, I’m good. And you’re no longer accountable.” But actually, it’s quite different. Tim had no part in my process of forgiveness. It was a personal journey that I took. For me not to forgive was to be locked in a prison that was full of anger, fear, and bitterness over what had happened. So that by forgiving him, it was actually releasing me from something, not him.

Suttie: Some researchers have mentioned particular conditions that make forgiveness more likely an outcome—for example, the person who wronged you showing remorse. What do you think helped you to decide to forgive Tim?

Boger: I don’t have a handbook. It was a journey. When he apologized, I didn’t say to myself, “Oh, he’s genuinely remorseful.” There was still trepidation. There was a moment when he apologized when I thought to myself, Who are you to apologize? Who are you to even think that I wanted to hear that? The journey took place out of Tim’s and my working together. We started doing presentations before I had forgiven Tim. We told our story, and the audiences asked questions. That part of our journey helped the other part—of being able to forgive him.

Suttie: What made you both decide to start presenting together, when you clearly didn’t want to?

Boger: I have no idea why I said yes. I’m not a public speaker. I wasn’t comfortable saying out loud in a crowd that I was gay. There was a lot of fear of getting up on that stage and telling that story. When you see what happens to the audience, though…this is what made Tim and I decide to move forward and just see what would happen.

Tim Zaal: I was definitely hesitant. I was already doing public speaking, and it was a one-man deal. When both of us first started doing it, we would sit on two chairs and we’d tell our story. Certain things would come out in the story when we were telling our parts, but there was definitely an elephant in the room that we both sort of ignored. We accepted it. The way I looked at it is that, eventually, the elephant would get smaller and smaller. It was literally an organic process that took place in front of people. He was going through a process of forgiving me, and I was going through a process of hating myself, being ashamed, feeling lesser than, and then having to forgive myself as well, which was a separate thing that went on at the same time.

Suttie: Matthew, did hearing Tim’s story help you have some empathy for him?

Boger: Not in the beginning. In the beginning, it was a little vengeful in some way… for me. Because I could bring him out in front of all of these people, and take him back to when he was 17—this monster in the alley—and let the audience redeem him. But that wasn’t working very well for me, spiritually. I wasn’t gaining any power or positive stuff in doing that. I was just becoming more negative. So I stopped doing that, and allowed us to organically tell our stories, and let the story show the empathy and humanity in the person.

Tim Zaal

Tim Zaal

Suttie: Tim, how did hearing Matthew’s story impact you?

Zaal: Up to that point in my life, there were a lot of people that I’d hurt, whether physically or mentally, and it put a face to all those other people who were basically anonymous. When the attack happened, I was a 17-year-old punk rocker, involved with wanton violence for selfish reasons, which was to make myself feel better. It just totally changed the entire thing and made it personal. This was a person with a family, a history; this was a human being, a spirit, a soul; before, it was just an incident. It actually brought it home more.

Suttie: You talk in the film about feelings of shame and guilt. Did that play into your journey toward self-forgiveness?

Zaal: Absolutely. It had gotten to the point where I didn’t even want to go to the museum. I would have to struggle to get up, get dressed, drive. And then at the presentation, I’m the bad guy. I have to sit there and be a thug, but I’m not a thug. I may look like a thug, and I’ve done a lot of bad things when I was younger. But I’m a big marshmallow in real life. Afterwards, depending on how the presentation went, I would have to process on the way home. Sometimes I’d need an hour phone call with a mentor friend of mine. And sometimes I’d feel like I’d had a great weight lifted off my shoulders just by talking about it. The hard thing to do, for anyone who talks about a negative past, is that you have to separate yourself from that action, from that person, and try to stay in the here and now, concentrate on the positives, concentrate on the future. That’s how I do it. I meditate, which has helped. But there are still bad days.

Suttie: What do you think the role of time is in forgiveness?

Boger: Forgiveness is not a quick process. It takes awhile. There’s a lot that goes into it. One of the fears of forgiveness is it’s almost like you’re grieving, because a part of yourself is dying—a part of you that you identified with, that made you who you were. And now you’re letting go of that. There are a couple of processes there: one is the journey of forgiveness, the other is the process of letting go of a part of you, and accepting a new role.

Suttie: It sounds as if you believe that the road to forgiveness is an individual journey—not one you can force. What do you think showing the film can accomplish?

Cohen: My hope is to tell their story, not to preach forgiveness. Let people see the possibilities and then decide if it’s something that works for them. We knew there were things in the film that would have an impact—for example, on restorative justice, which Tim is a walking billboard for, and on issues around gay bashing—so we obviously wanted to touch on those. But, overall, we wanted to say, “Here’s a story of forgiveness. Take from it what you will.”

A scene from Facing Fear

A scene from Facing Fear

Boger: The more you put it out there, the more people it will impact. Hopefully someone else won’t have to go through anything even remotely like this because of who they are. Tim and I are always clear—we don’t want this to be a gay/straight issue only. Hatred and intolerance are not just against one group of people—they happen against many groups.

And so our story relates to a lot of things that are going on, from bullying to whatever, wherever people don’t feel like they have a voice. Hopefully, they’ll realize they do and use it to be responsible.

Zaal: When I get a card from a school or a group that we spoke to many months ago, they may say that we’ve changed their lives, made them think about how they treat others. Or, I’ll get emails or twitters from former skinheads or people who are right on the cusp, right on the fence of getting out of that lifestyle, telling me, “Your presentation or your story helped me to make that final step away from that lifestyle.” Sometimes they are few and far between; sometimes there are a lot. But, even if it’s one, it’s worth it, because if we can influence someone else to make some of the changes we’ve made—to go over that fence—then we’ve accomplished something.

Suttie: What’s next for the film?

Cohen: We are planning to do a big educational push—to bring this to schools and offer some kind of study guide to go with it. We’ve already shown it to schools and seen the kind of impact it can have. We did a screening in Long Beach, where the kids came from pretty rough neighborhoods, and they ended up asking these really insightful questions…in addition to giving Matthew a hug, and Tim too. Kids don’t usually show their raw emotions that much, and these kids were—they were relating it to their lives. We did a screening in Marin County, and that was very different; but the kids there were also impacted by it. So seeing how it can impact all these different societal groups makes me want to get it out there.

The movie Facing Fear will be screened in San Francisco and Berkeley in early August as part of the Jewish Film Festival. For more information about these screenings and other opportunities to see the film, or to purchase tickets, please go to facingfearmovie.com.

Comments