Do you marvel at the wonder and beauty of life? Do you feel a positive emotional connection to nature?

If so, you might be prone to awe, that goosebumpy sensation that we get in the presence of something profound: something greater, more powerful, or more eternal than ourselves. It arises when we encounter things that challenge our sense of what’s normal or possible. Awe is feeling moved by remarkable art, expansive nature, incredible ideas or people, or acts of mind-blowing skill, among other things.

But you don’t need to visit the Grand Canyon or the Taj Mahal to feel awe; a 2015 study in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology suggests that watching an awesome nature video or even gazing up at very tall trees can do the trick. And feeling awe has been linked to generosity, humility, better health, and sharpened thinking, among other benefits. Basically, awe makes the world a better place.

Last year, we created an online awe quiz and invited readers to take it. It measures how much awe a person tends to experience in life, and more than 6,000 people have taken it so far.

The results suggest that you readers are an awesome group—the average score was 63 out of 75, putting you in the “high awe” range. This high score suggests that you feel wonderstruck regularly, and tend to be comfortable with the uncertain.

But do some people feel more awe than others? Who in the Greater Good community experiences the most awe? Based on our analysis of the quiz responses, here’s what we learned.

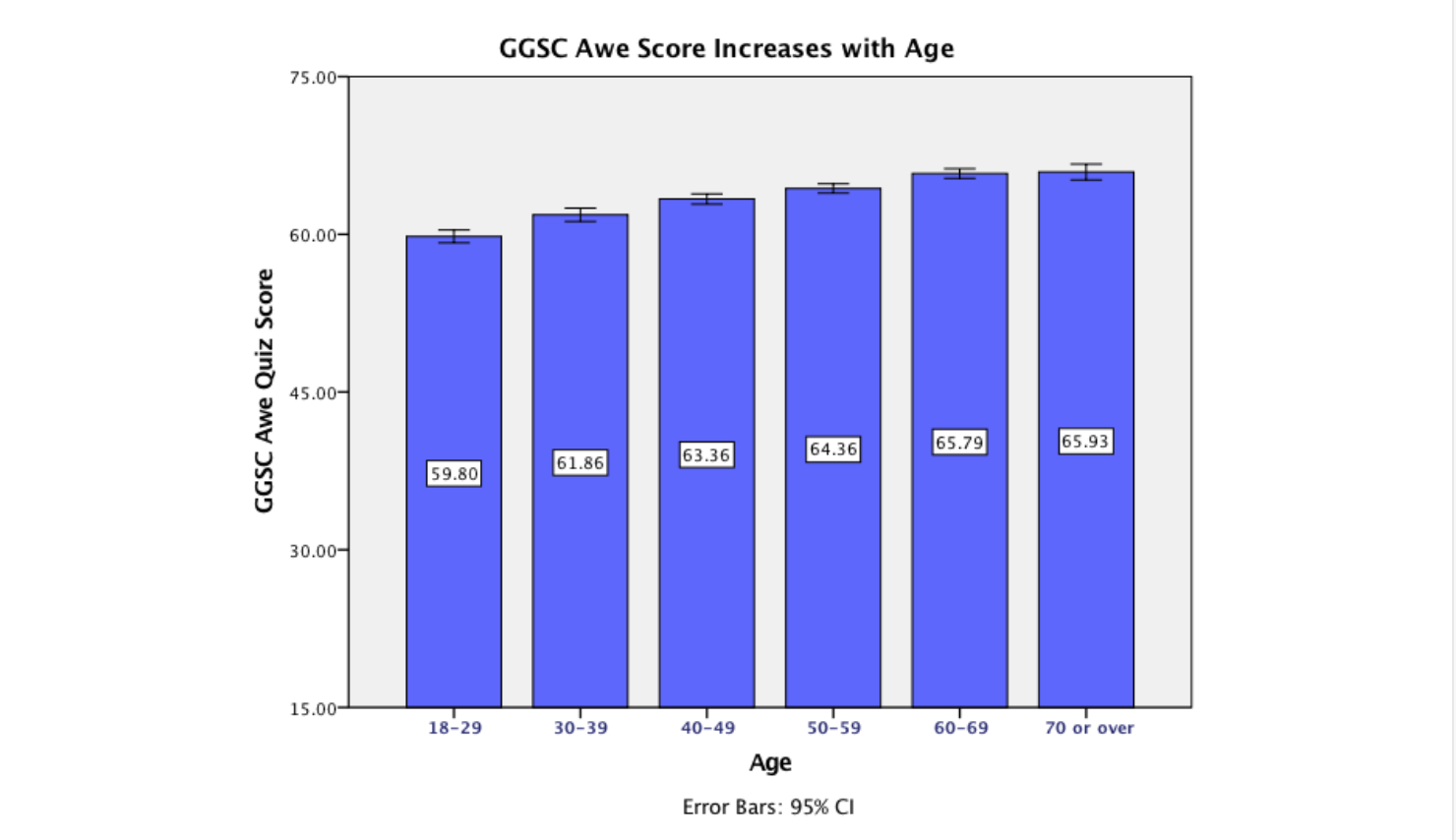

The older you are, the more awe you feel

While we sometimes describe awe as feeling “childlike” wonder, adults feel awe, too. In fact, the older you get, the more awe you tend to feel. Among those who took the quiz, awe increased significantly until around age 60, at which point it seemed to plateau. That’s something to look forward to!

We asked Dr. Paul Piff, assistant professor of psychology and social behavior at UC Irvine, to speculate on this pattern. He reasons that “a sense of novelty and gratitude for the world seems positively associated with age.” One theory of motivation suggests that we tend to direct our resources toward more emotionally meaningful goals and activities as we get older, Piff notes, and “in the world of meaning, experiences of awe are among the most meaningful people can have.”

Gender makes a difference

Women’s awe scores were greater than men’s: Women scored 64 out of 75 on average, compared to men’s 61. While it may be tempting to conclude that women are extra awesome, these results don’t necessarily imply a deeply rooted or biological sex difference, because people were answering surveys about themselves.

In fact, women tend to score higher than men on most Greater Good quizzes, which could be less reflective of their levels of well-being-related traits and more reflective of the way they tend to respond to online quiz questions. For starters, responders for this quiz were overwhelmingly women: 78 percent vs. 21 percent men (37 people indicated their gender as non-binary.)

When we asked Piff to weigh in on why women scored higher in awe, he speculated that it could come down to how awe tends to make us feel small.

“Men score higher on dominant traits like narcissism and entitlement, and they tend to be more status-seeking and power hungry—cultural norms play a big role in all this,” he says. “But awe, by virtue of making you feel less powerful than something else, may not be something men prioritize or value; maybe it even threatens their masculinity.” So maybe social norms steer men to avoid feeling awe.

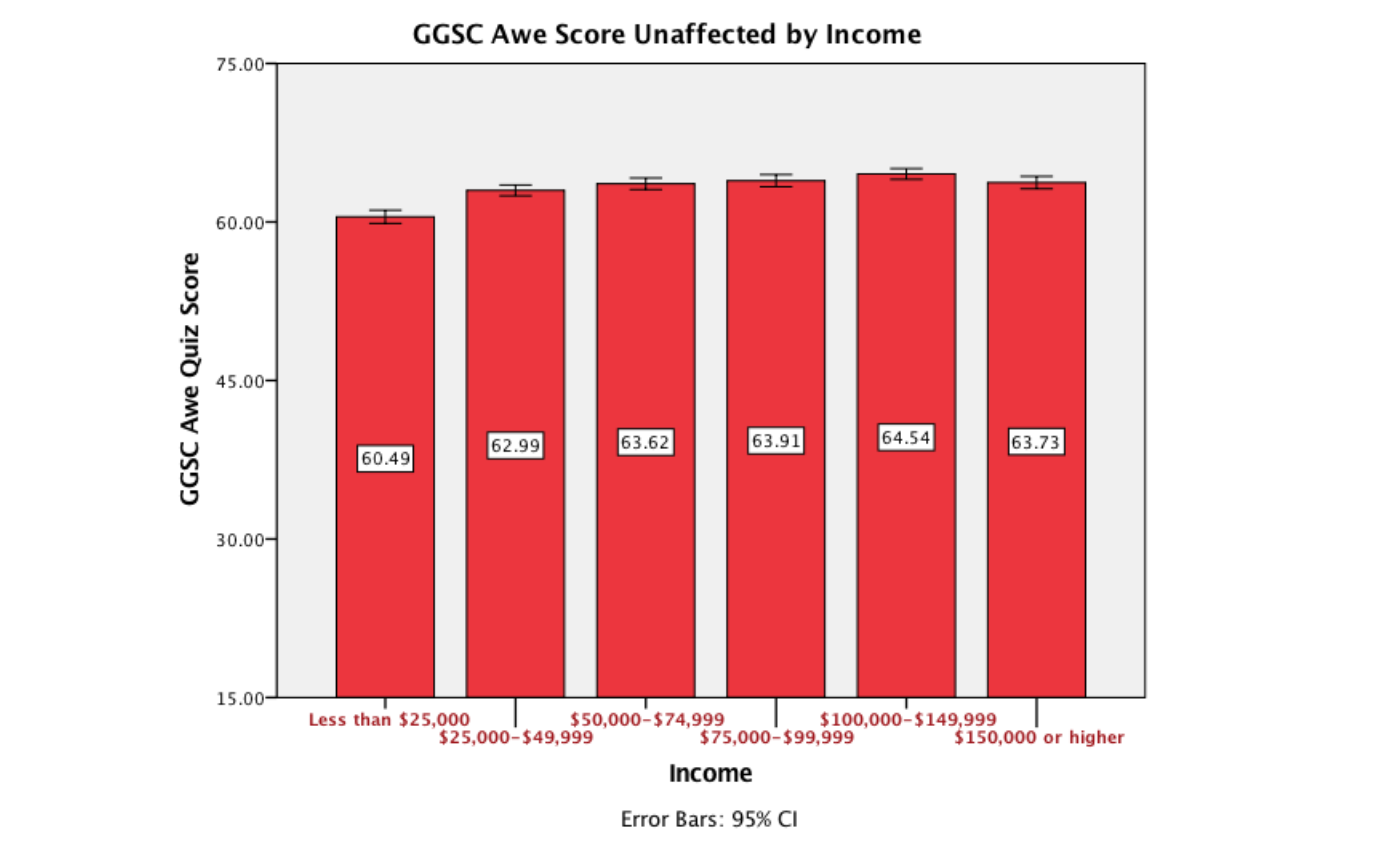

Your income and location matter less than you may think

Where you live doesn’t seem to matter at all. We did not find any notable difference in awe scores between people who live in rural areas, suburban neighborhoods, or cities.

How much money you earn doesn’t seem to make a big difference, either—though people who make less than $25,000 per year did report lower levels of awe. The good news is that if you make $25,000 or more, whether your annual salary is $50,000 or $150,000, you are likely to experience similar levels of awe (among Greater Good readers, at least).

In his own nationwide study, Piff found that higher income may be related to less awe. “If income relates to feelings of power and entitlement, those are inimical to feelings of awe, which relate to feelings that one is part of something greater than oneself,” he says. “Wealthier individuals may be less prone to awe and less likely to seek out awe-inspiring experiences for those very reasons.”

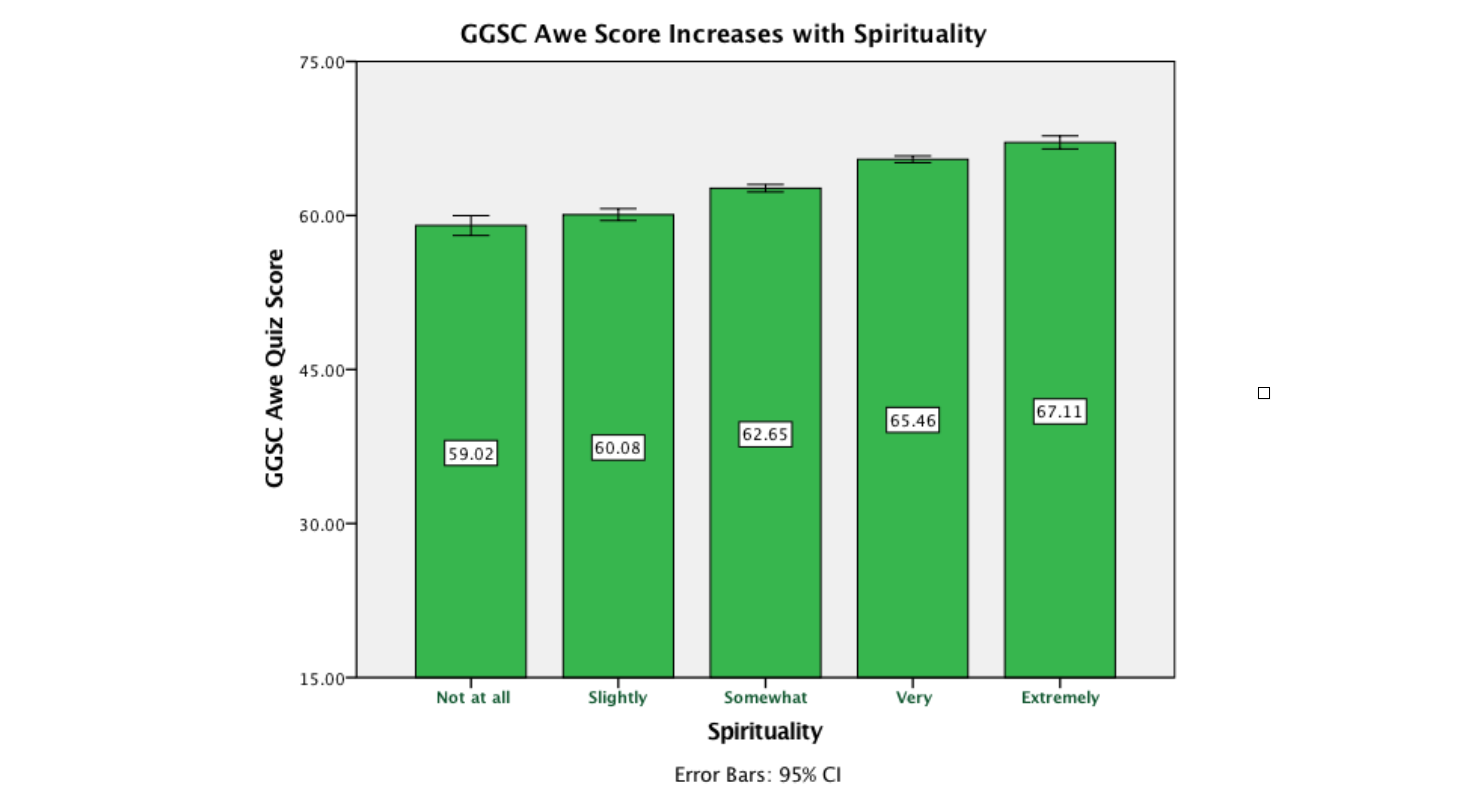

Spirituality and awe are connected

The Greater Good awe quiz results show a clear link between awe and spirituality—that is, how people answered the question, “How spiritual are you?” The more spiritual you say you are, the more awe you tend to feel.

Spirituality is often described as a feeling of connectedness to something greater than ourselves, and typically involves a search for meaning and personal growth. Extremely spiritual people scored an average of 67 out of 75, whereas people who see themselves as not at all spiritual scored 59 on average. That’s a 13 percent difference in awe scores.

How can you become more awe-some? Start by scheduling in more awe-inspiring moments, such as spending time in nature or around your favorite art. Our website Greater Good in Action can help you build awe with a collection of activities that take as little as four minutes:

- Watch an awesome video that changes your perspective.

- Take an awe walk somewhere vast or new.

- Read an awe-inspiring story.

- Pay attention to nature—and bring a camera!

- Write about the last time you experienced awe to trigger that feeling again.

What do you think of our findings? Were they shocking or predictable? Let us know in the comments below—and be sure to take the awe quiz if you haven’t already.

Comments