My 33-year-old daughter and I were on a walk together through the hills of Missoula, Montana. It was a clear, cold, crisp afternoon.

My wife and I were visiting her, her husband, and their two-year-old son in their new home after they had spent the previous year and a half living in our home in Northern California. As we walked along a trail just wide enough for us to be side by side, I had a strong feeling that my daughter had some residual feelings of anger toward me and her mother.

Several months earlier, during the time they were living with us, some serious miscommunication and misunderstandings had taken place. At that time, she had voiced that she was processing a lifetime of feelings, a lifetime of family dynamics she was frustrated with. At one point, she said she felt that her childhood role was to smooth out family difficulties to make it easier for her parents and her older brother.

Now, as an adult and the mother of a young child, she wanted to change this pattern. She was working to heal her painful feelings from the past and transform them to improve her own well-being and create healthier family relationships.

We came to a place on the path that seemed like a natural stopping point. The views of snow-covered mountains were spectacular. As we stopped, I turned to her and asked, “How are we doing?”

I wanted to better understand what she was thinking and feeling. In particular, I wanted more clarity about gaps—the differences in her experience and mine—and how we might find more alignment in our relationship.

There can be gaps between how things actually are and how we want them to be in the closeness of our relationships with a partner, children, and parents. There can be subtle—or not-so-subtle—differences between our own experiences, emotions, and needs and the experiences, emotions, and needs of others. Sometimes it feels like our only choice is to give up and not do or say anything so we don’t make things worse. Is it any wonder when we let anxiety rule, stop truly listening to each other, and at best give our conditional commitment to a relationship?

There is another way, which is the practice I call “mind the gaps.” That means not avoiding gaps or the discomfort they cause; it entails being curious about them, dropping your stories, and listening more closely. Gaps and discomfort will appear, sooner or later—and there are skillful and effective ways to address them and improve our relationships.

Tips for closing the gap

To me, when it comes to the practice of minding the gaps in relationships, the four most important words are the ones I asked my daughter: “How are we doing?”

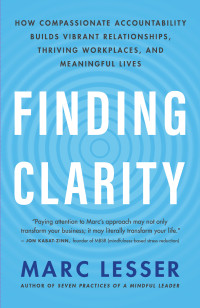

Adapted from the book Finding Clarity: How Compassionate Accountability Builds Vibrant Relationships, Thriving Workplaces, and Meaningful Lives.

© Copyright ©2023 by Marc Lesser. Printed with permission from New World Library.

Adapted from the book Finding Clarity: How Compassionate Accountability Builds Vibrant Relationships, Thriving Workplaces, and Meaningful Lives.

© Copyright ©2023 by Marc Lesser. Printed with permission from New World Library.

Sometimes, this is all that is needed to assess and explore the status of any relationship. “How are we doing?” can be used to launch a conversation with our partner, our children, our parents, our friends.

Particularly with people we love, these four words are a means for exploring the quality of that love. We ask because we care. We want to know the other person’s experience and where they feel aligned and not aligned, and we want to know how they think we can eliminate or narrow any gaps. We ask someone what, if anything, might improve the way we care for them. This inquiry in itself is an expression of our commitment to the relationship and our desire for it to embody shared values.

How we ask this question makes a big difference in how it is answered and in the conversation that follows. As you approach the “How are we doing?” conversation, try to keep these things in mind.

1. Be ready to drop the story. Notice, before having important conversations, if you’re already upset, worried, or mad about something, and be curious about that. Do you already think you know the answer, and so the question is more of a statement that you recognize something is missing, lacking, or wrong? Is the question really a prelude to a request for something you need from the other person? Before talking, recognize what you think, expect, or assume the other person will say. Identify your own interpretation of events. Then when the talking starts, drop your story.

2. Be curious, not furious. Ask in a spirit of genuine curiosity and openness. After you ask the question, be concerned only with understanding the other person’s story. Be ready to listen to the other person’s perspective and experiences, and be willing to be surprised. Try to avoid reactivity. If someone says something that makes you react in the moment, breathe and put that aside to listen, and really hear, what they have to say.

3. Align body language with intentions. We convey this openness with our tone and body language as much as with our words. Does our voice and manner convey doubt, anxiety, or defensiveness—or caring, respect, and the willingness to have a genuine conversation? We can’t pretend that fears don’t exist, but we can also nonverbally convey our core motivation to express caring in order to improve our connection.

4. Listen for understanding. Our good intentions for asking the question are not enough. In the moment, our most important job is to listen. Explore really listening without preconceived ideas. Experiment with listening not only for content but for feelings, for lack of alignment, as well as for possibilities and ways to solve problems together.

5. Mind the gaps. Of course, how the other person responds will determine the conversation that follows, which may require a good deal of openness, presence, and skill. Our response to whatever the person says will require continued openness, trust, compassion, clarity, honesty, and integrity. As you talk, clarify the gap between your experience of the relationship and your vision or aspiration for what a healthy relationship looks like and feels like. This alone is helpful, since it defines the problem.

6. Cultivate a clear vision. What’s their ideal for how you and others perceive a healthy and caring relationship? In a work context, this might be more about competence and productivity, as well as trust and connection. What’s the ideal for what they or your team is trying to accomplish? Use the answers as seeds for further discussions about shared goals and how to bridge the gaps you’ve identified for reaching them. Focus on problems not to assign blame but to discover what you both can do to fix them, even in small ways, which will foster a sense of growth.

7. Don’t wait. If you know who you need to talk to, don’t wait. If you aren’t sure whether someone has an issue, don’t wait. If all seems “fine,” confirm that. Don’t wait to ask “How are we doing?” and ensure that your “story” is the same as everyone else’s.

This one simple question just might change your work, your relationships, and your life.

My conversation with my daughter wasn’t easy. I was surprised, and not, by the intensity of her feelings. I discovered that many of these negative feelings had nothing to do with me. She was feeling exhausted as a new mother. She was struggling through a major transition as they cultivated a new life in Missoula. She also wanted to rebuild our trust and create an easier, more loving connection.

It was an important conversation. My relationship with my children is important and meaningful to me beyond words. I came away with a deep sense of connection while knowing there was more work to do, more conversations to be had, more listening and understanding to cultivate.

Comments