When people are afraid that something bad will happen to them because of their decision to speak up, in most cases, they won’t do it. And can we really blame them? This is, seemingly, leadership’s failure to foster the type of culture that encourages and rewards people for speaking up.

Whether our experience is real or perceived—and sometimes our perception is our reality—if it feels dangerous and like we may be punished for sharing our ideas, concerns, disagreements, and mistakes, the likelihood of our speaking up decreases.

Professors Ethan Burris and Jim Detert call the process of deciding whether to speak up “voice calculus,” during which people “weigh the expected success and benefits of speaking up against the risks.”

There are plenty of examples where not having a speak-up culture proved disastrous, including the Boeing 737 MAX tragedies that resulted in two plane crashes and 346 lives lost—or, more recently, the Titan submersible disaster, where two former OceanGate employees separately voiced similar safety concerns about the thickness of the hull, but found their voices dismissed.

The stakes need not be life and death for employees to feel that the risk to speak simply isn’t safe or worth it. And, when people choose to keep their ideas, concerns, disagreements, and mistakes to themselves, everyone loses. The bottom line, for everyone, is that organizations with speak-up cultures are safer, more innovative, more engaged, and better-performing than their peers.

So, how do you foster a speak-up culture? It starts with resisting the urge to manipulate employees—and ends with making it safe and worthwhile for them to share their truth.

The costs of manipulation

There are two psychological phenomena that affect the outcome of our voice calculus and a propensity for staying quiet: gaslighting and toxic positivity.

Gaslighting occurs when someone is manipulated by psychological means into questioning their own reality. Sounds fun, I know.

For example, someone dares to risk sharing with their leader how they feel, and their leader essentially responds with, “You’re incorrect. You don’t feel that way.” Of course, this is a ridiculous assertion. While we can debate facts and figures, arguing that someone’s feelings are invalid is quite inhumane and certainly lacks emotional intelligence.

A “gaslighter” uses four main techniques (with examples) to influence their victim:

- Reality manipulation (“that’s not what happened”)

- Scapegoating (“you are the problem” or “they are the problem”)

- A straight-up lie (“this contract is designed to protect you”)

- Coercion (“do this, or else”)

Convincing others that they themselves are the problem rather than acknowledging and dealing appropriately with the very issue they are raising is a form of gaslighting. This is also abdicating the responsibility of leadership.

Toxic positivity is a more subtle cousin, if you will, of gaslighting. It’s a “good vibes only” approach, where we’re allowed to talk only about good things and the future—no lamenting about the past or talking about the real challenges at hand.

For example, 30% of the workforce was just laid off, and talking about it to cope and grieve is off limits: “Are you a part of the problem or do you want to be a part of the solution?,” people may say.

Heedless positivity is not the same thing as grounded and realistic optimism. Toxic positivity is the belief that people should always remain positive, no matter how dire the circumstances.

Unfortunately, wishing negativity away is not a great strategy. The avoidance of those hard and real emotions is unproductive and unhealthy. Toxic positivity is dysfunctional emotional management, without the full acknowledgment of negative emotions, particularly anger and sadness. These, of course, are part of the full spectrum of human emotions.

Making space for authenticity

When organizations encourage and reward people for sharing how they truly feel and make space for expressing emotions beyond the positive ones, it can be an advantage.

As Harvard Medical School psychologist Susan David teaches us in her 2016 book, Emotional Agility, emotions are data that can inform us and others of what’s going on. When a broader spectrum of emotions is safe and welcome within organizations, we can make better, more sound, holistic, and wise decisions.

To avoid gaslighting or toxic positivity—and, perhaps most pressingly, being fired—people turn the other cheek, put their head down, share the truth but not the whole truth, or just keep walking by. Importantly, it doesn’t matter whether their fears are well-founded or not.

Again, our truth is but our perception. Our brain releases cortisol whenever we sense a threat. Cortisol is the same neurochemical that during our primal days instigated us to either head for the hills or stay and fight. While our surroundings have evolved, our neurobiology hasn’t.

When we perceive a threat, our brains release cortisol—our pupils dilate and our muscles tense just as readily inside the four walls of our office or videoconference screen as they did on the plains. The only difference is that now we’re worried about losing our livelihood, not about being eaten by a large cat. But it feels as critical, as if we were worried for our lives. Cortisol is, after all, designed to keep us safe. If it feels dangerous to speak up, the likelihood that we will diminishes.

So, how do leaders create an environment where people feel it’s safe and worth it to speak up?

How to create a speak-up culture

They can, quite simply, encourage and reward people for sharing their truth.

When we join a team, we very quickly learn the culture and norms—what’s accepted and what’s not. We may hear about someone else’s attempt to share an idea, feedback, concern, disagreement, or mistake. Perhaps it went well; perhaps it didn’t. We may even be so bold as to contribute to a conversation. What happens next typically dictates how we, and others, will behave going forward.

Some may speak up and be encouraged and rewarded for doing so. Still, people may speak up and be ignored or, worse, punished. Some may never find out how leadership would react to what they are thinking because they do the voice calculus in their head and choose to refrain from speaking up at all. When people choose not to speak up, they tend to hold back for two reasons: fear or apathy.

Before someone chooses to speak up, they consciously or unconsciously ask themselves:

- Is it safe? Do I feel there is enough psychological safety present for me to take the risk to my job, relationships, and reputation to speak up?

- Is it worth it? Do I perceive that speaking up will yield a useful, positive impact? (This is what’s known as “perceived impact.”)

The graph above maps out the continua of fear to safety and apathy to impact. Obviously, the top-right quadrant is the sweet spot. When safety and impact are high and maintained, you likely have a healthy speak-up culture. This is not a place of fearlessness, but rather a place where people fear less.

The bottom left is a miserable place to be. I’ve been there, and I’ve seen others there, as well. It’s an unhappy marriage between fear and apathy, where it feels neither safe nor worth it to speak up. Quiet quitting (putting one’s head down, doing the bare minimum, waiting until something better comes along) or resignation likely happens here.

The other two quadrants are less straightforward. The top left is characterized by safety, but low impact. You may feel safe to confront a friend, colleague, or boss, but you do not believe doing so would lead to any meaningful change. Perhaps this is because of bureaucracy or a larger systemic issue, or because a personal change in habits would be highly improbable.

The final quadrant in the bottom right—low safety and high impact—is where Ed Pierson, the senior manager at Boeing working on the 737 MAX, found himself leading up to the first crash in October 2018. The cost of remaining silent was too high. This is the reason a speak-up culture is ever more important in high-stakes and potentially dangerous lines of work and environments. Pierson and others courageously risked their jobs, livelihoods, reputations, and relationships to speak up. In his case, after repeated attempts and dead ends, Pierson ultimately decided to whistleblow in December 2019, testifying before the U.S. Congress.

This was also the case for Kimberly McLear, a whistleblower who served in the U.S. Coast Guard from 2003 to 2023. As a queer Black woman with a Ph.D. and highly decorated in the Coast Guard, she was unfortunately the target of workplace bullying, psychological harassment, and intimidation.

McLear felt harassed because she brought a differing opinion and point of view; because of her gender, race, sexual orientation, and same-sex marriage; and because she became a trusted confidante across the Coast Guard. In 2016, after enduring two years of direct abuse, she made the conscious decision to speak up, “not only for [her] own survival,” but also to shine a light and educate others on the injustices she felt and saw were occurring more broadly in the organization. Following her speaking up as a whistleblower, she experienced further retaliation.

Today, McLear continues to be an outspoken advocate for helping leaders and organizations create workplaces and communities where people feel they matter, belong, and can be their full, authentic, and healthiest selves.

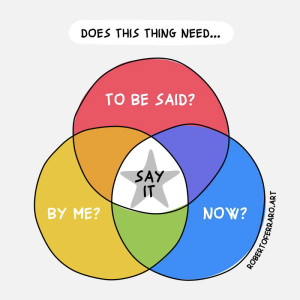

This is not a license to share whatever we want, with whomever we want, and whenever we want. Emotional intelligence and situational awareness ought to be nurtured and expected. Comedian Craig Ferguson is credited with these brilliant questions that can form a Venn diagram: “Do is need to be said? By me? Now?”

That’s the responsibility of every employee. But the special responsibility of leaders is to value the voice and input of the employees and team members, by making it both psychologically safe and worth it to speak up. To both encourage people to speak up and reward them for doing so, especially when they bring up hard things to hear. Creating such an environment is the responsibility and the advantage of leaders at every level who want to be great at leading, and who want to create a better version of humanity while they do it.

Comments