Do you perseverate over personal setbacks, failures, or whatever makes you feel inadequate? Do you berate yourself for feeling upset about what’s wrong in your life, with other people, or the world, in a counterproductive attempt to be happy? If so, it could be time to exercise some self-compassion, which is the opposite of catastrophizing and self-criticism. According to Kristin Neff, who was a pioneer in the scientific study of self-compassion, it is grounded in:

- noticing or being aware of our own mental states,

- harboring a sense of shared humanity, and

- using a kind and encouraging inner voice.

Many articles published in top-tier scientific journals report benefits of self-compassion, from increased stress resilience to better relationships to greater success at achieving goals. Neff and her colleagues have developed practices like taking a self-compassion break, as well as extensive training programs for strengthening self-compassion, in addition to validated surveys that can reliably measure self-compassion.

We adapted Neff’s Self-Compassion Scale to create the GGSC self-compassion quiz, which 20,000 of our readers have completed—and we analyzed how people’s scores vary as a function of age, gender, education, income, ethnicity, and political views. Here’s what we discovered.

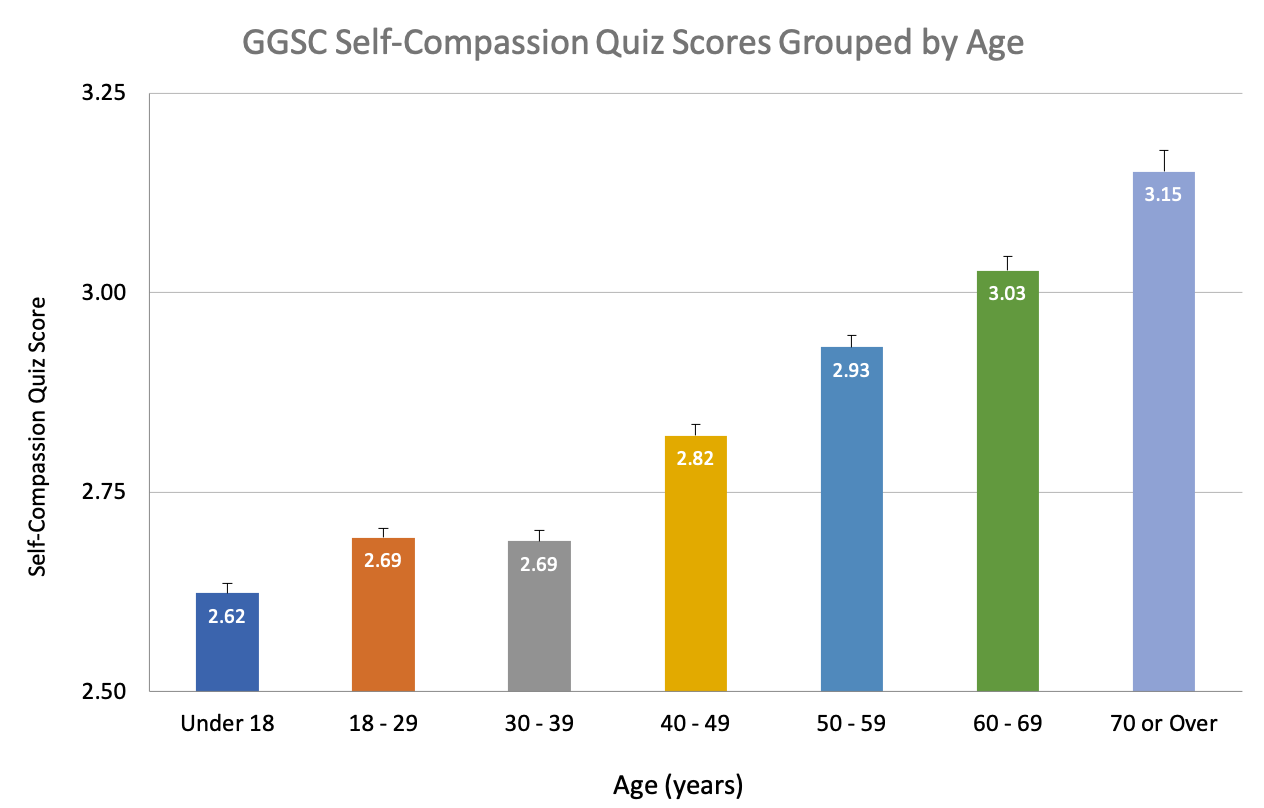

Self-compassion rises with age

There was a significant correlation between quiz scores and age, with scores climbing higher in each decade after the 30s.

Our youngest quiz takers (under 18) scored lowest in self-compassion, perhaps reflecting some of the peer sensitivity, social comparison, and identity-related challenges that teens often grapple with. While scores increased for 20-somethings, they stayed flat into the 30s. Does self-criticism prevail during early adulthood, when people are in the early stages of their professional and family lives?

For 40 year olds and beyond, self-compassion scores show a pattern of consistent, stepwise increase, which suggests that as quiz takers get older, they increasingly manage feelings and address difficulties in kinder and more constructive ways.

Importantly, this result does not tell us why older people scored higher in self-compassion. We cannot conclude that the relationship between self-compassion and age is causal, that is, that getting older makes people more self-compassionate. Because we do not have longitudinal data (measurements from groups of people taken repeatedly over many years), we cannot make claims about whether age-related differences in self-compassion are linked to trajectories of development and maturation or specific environmental factors that define what people in different generations have lived through.

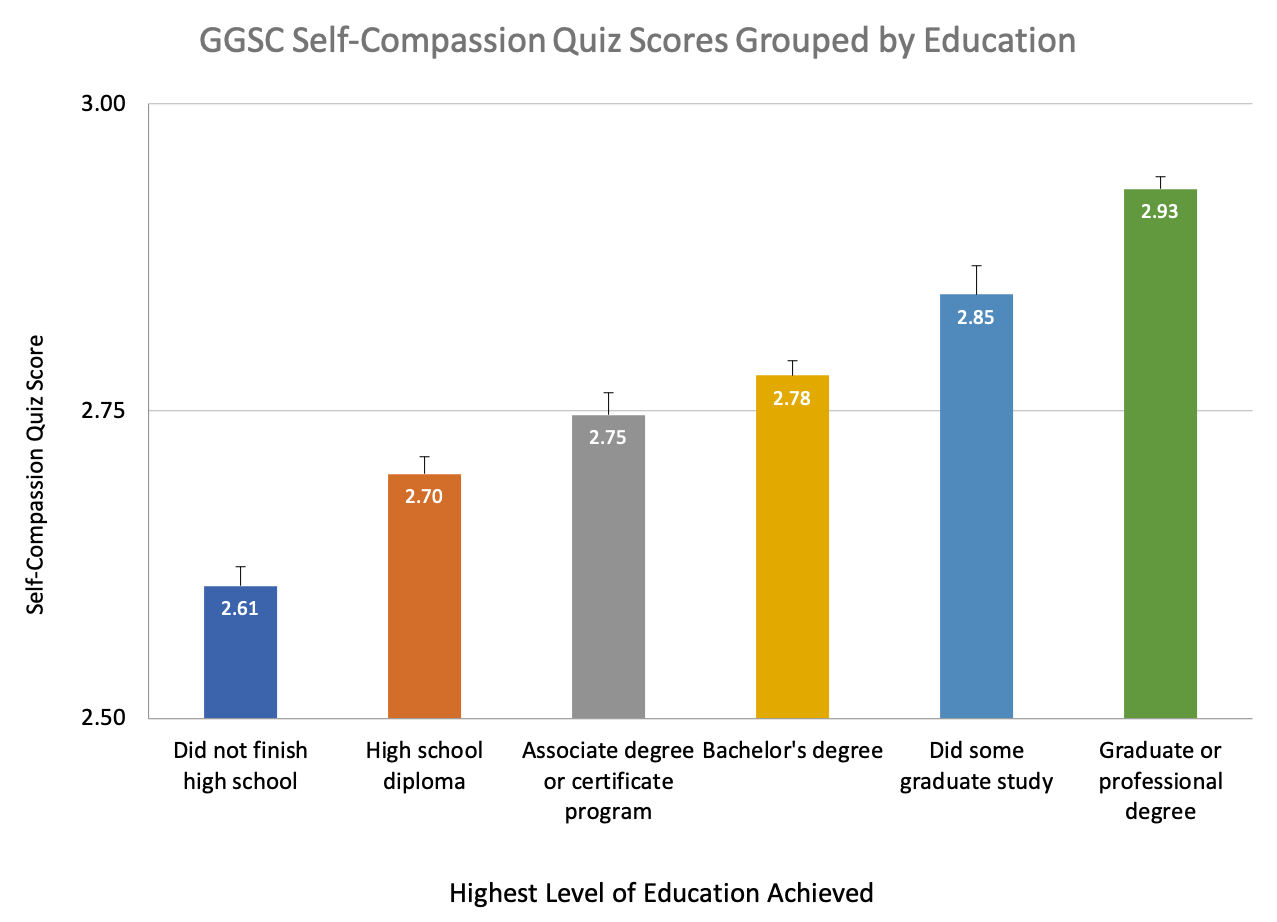

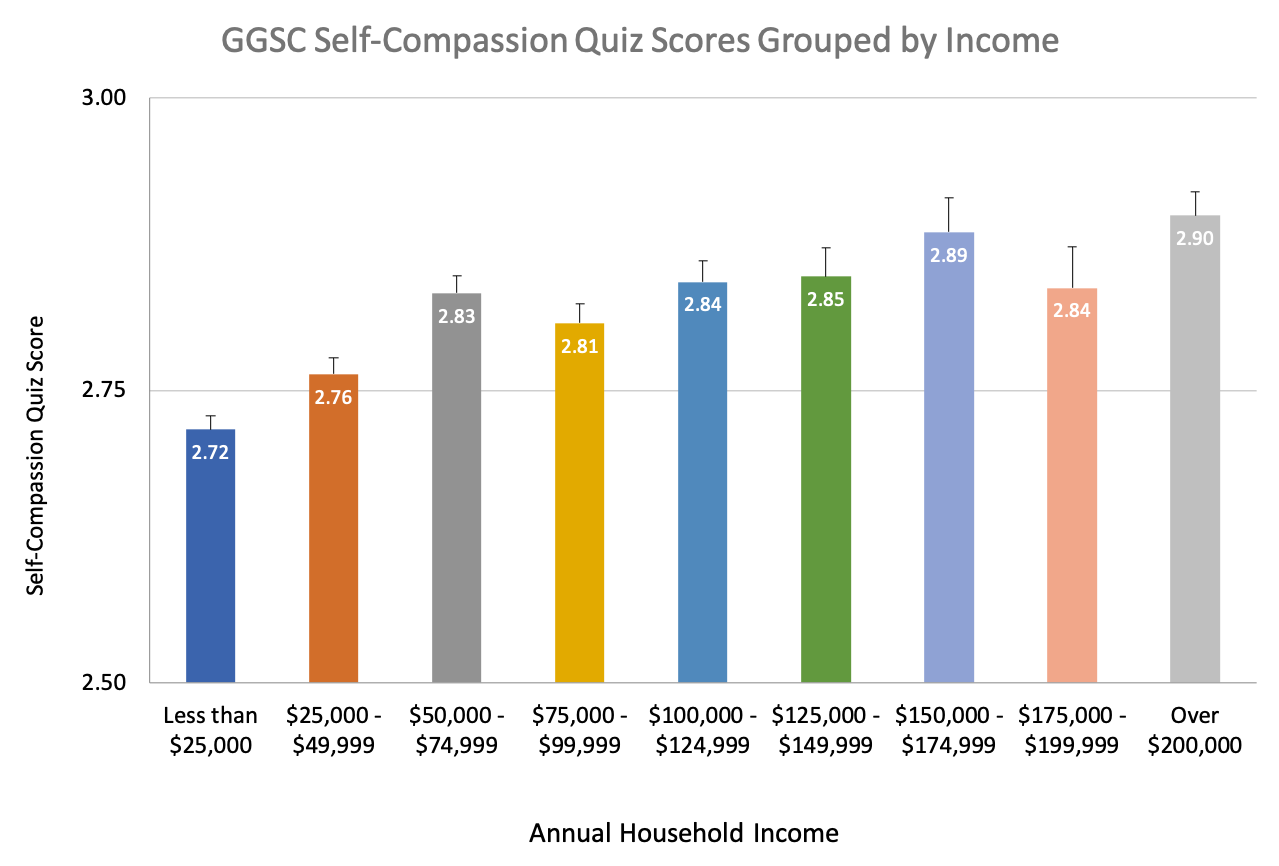

Self-compassion seems to rise with education and income—but that might be because those also rise with age

Quiz takers who reported more educational attainment and greater household income also scored higher in self-compassion. That pattern is similar to the one of self-compassion increasing with age. Because being older is usually associated with greater educational attainment and earned income, it’s useful to compare the relative strength of each factor in predicting self-compassion scores. In other words, is the effect of educational attainment or income on self-compassion mostly a function of older age, or vice versa?

Follow-up analyses suggest that age is the stronger predictor of self-compassion scores compared to educational attainment or income. In fact, when we control for age and education, annual income explains less than 2% of the variance in self-compassion scores.

We also can’t establish a causal relationship between income, education, and self-compassion. Because the relationship is correlational, it is just as likely that more self-compassionate people pursue further education or earn higher incomes over the course of their lives. In fact, studies that assign people to self-compassion training, and compare the impact to people assigned to a control group, have reported improved motivation and goal pursuit, which suggests that for these factors, the influence may be reciprocal.

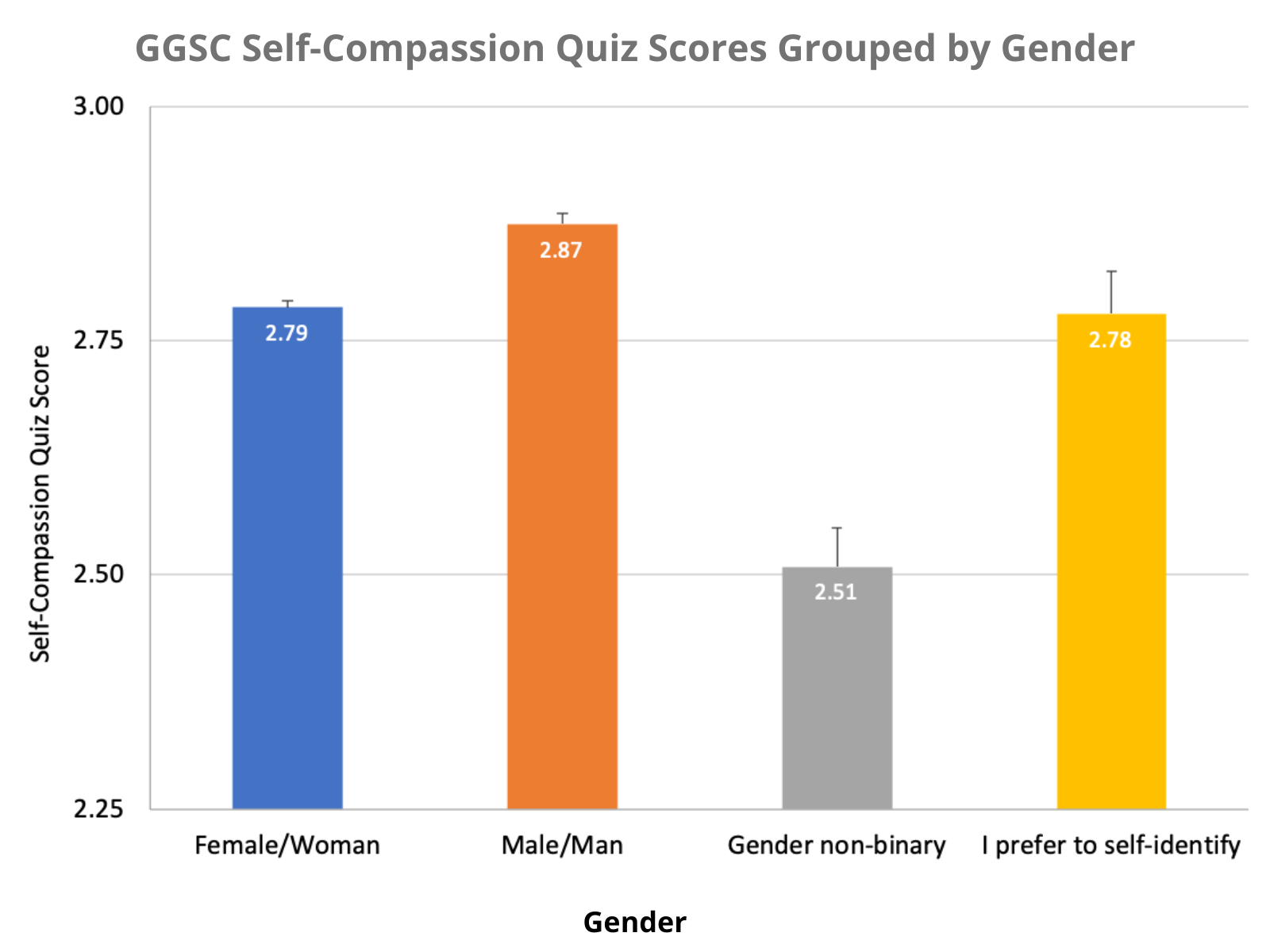

Men score higher in self-compassion than women and non-binary people

Perhaps surprising for a characteristic that some might consider a “soft skill”—relating to things we dislike about ourselves with the same compassion that we might spontaneously offer to others—men scored higher in self-compassion that women and people who are non-binary.

That means men more willingly endorsed statements like “When something upsets me, I try to keep my emotions in balance” or “I try to see my failings as part of the human condition” with choices like “Fairly often” and “Almost always.” Men also responded less favorably to statements like “When I’m feeling down, I tend to obsess and fixate on everything that’s wrong.”

Though the GGSC self-compassion quiz is meant to be scored as an average computed from responses to all 12 statements, a closer look showed that women endorsed two of the self-compassion-indicating statements more strongly than men: “I try to be loving toward myself when I’m feeling emotional pain” and “When I’m down and out, I remind myself that there are lots of other people in the world feeling like I am.”

These two statements are more about nurturance and emotional connection than others on the quiz—which suggests that women may score better on the “kind and encouraging inner voice” dimension of self-compassion, but not the other two. Quiz takers who indicated being gender non-binary scored consistently lower than men or women, and endorsed all 12 statements in the direction of lower self-compassion.

A first takeaway from this pattern of data is that men, women, and non-binary people score differently on the three key dimensions of self-compassion: 1) mental calmness and stability in the face of distress, 2) a less critical view of oneself relative to other people, and 3) a supportive and loving inner voice. Namely, responses to specific questions on the quiz suggest that men score higher on both calmness and being less self-critical, while women score higher on the supportive and kind inner voice dimension of self-compassion.

That pattern echoes conventional gender roles in many cultures, and suggests the possibility of targeted opportunities for enhancing self-compassion that match the need. For example, women can work on being less self-critical and more resilient, and men can work on inner kindness.

Regrettably, the scores of gender non-binary people suggest a more global challenge. Are the day-to-day struggles of not conforming to conventional gender roles detrimental to self-compassion? Further research could shed light on this issue, and perhaps make a stronger case for openly embracing and explicitly easing the burdens faced by people who identify as non-binary in terms of gender.

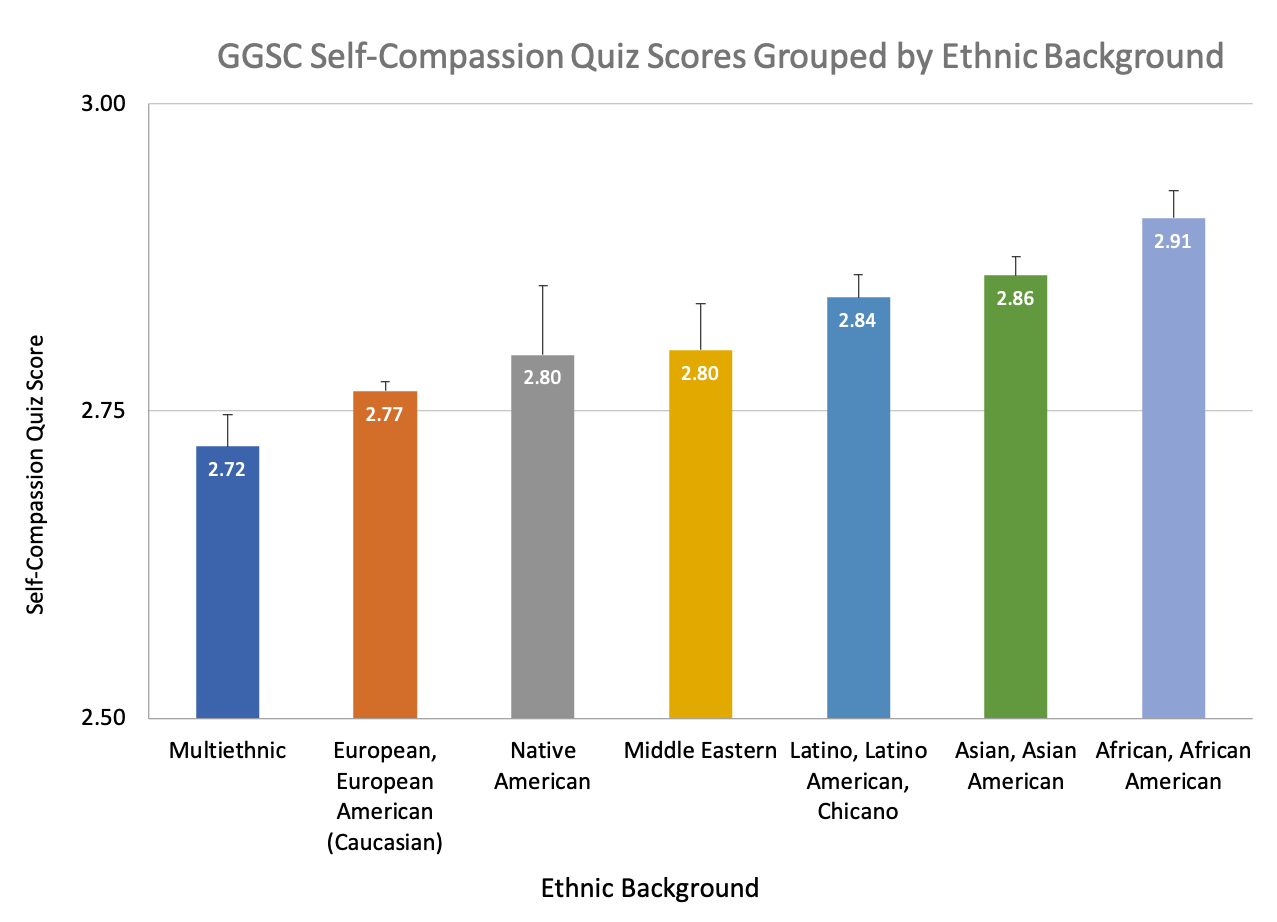

White people have lower self-compassion

Quiz takers who identified as Caucasian scored lower on self-compassion than those who identified as Black, Asian, and Latino, which highlights the need for additional research into aspects of people’s identities that strengthen or sustain characteristics (like self-compassion) that benefit well-being.

For example, scientists could explore whether specific beliefs, experiences, rituals, social mores, or cultural norms make self-compassion more likely in some people or groups than others. Conversely, are there long-held facets of white American culture, like excessive self-criticism or competitive zeal, that diminish self-compassion and in turn constrain overall well-being? Regrettably, people who identified as multiethnic, similar to the findings for non-binary people, scored lowest in self-compassion, suggesting again that straddling identities that are typically seen as separate may be particularly challenging to people’s self-compassion.

In fact, researchers at the GGSC are very interested in this topic. One of our major scientific initiatives, GGIA 2.0: Making the Science of Character Virtue More Practical, Engaging, and Impactful, is examining people’s responses during their Pathway to Happiness to better understand how to leverage their individual characteristics, needs, and strengths (such as self-compassion) to provide the most useful, appealing, and impactful guidance toward strengthening well-being.

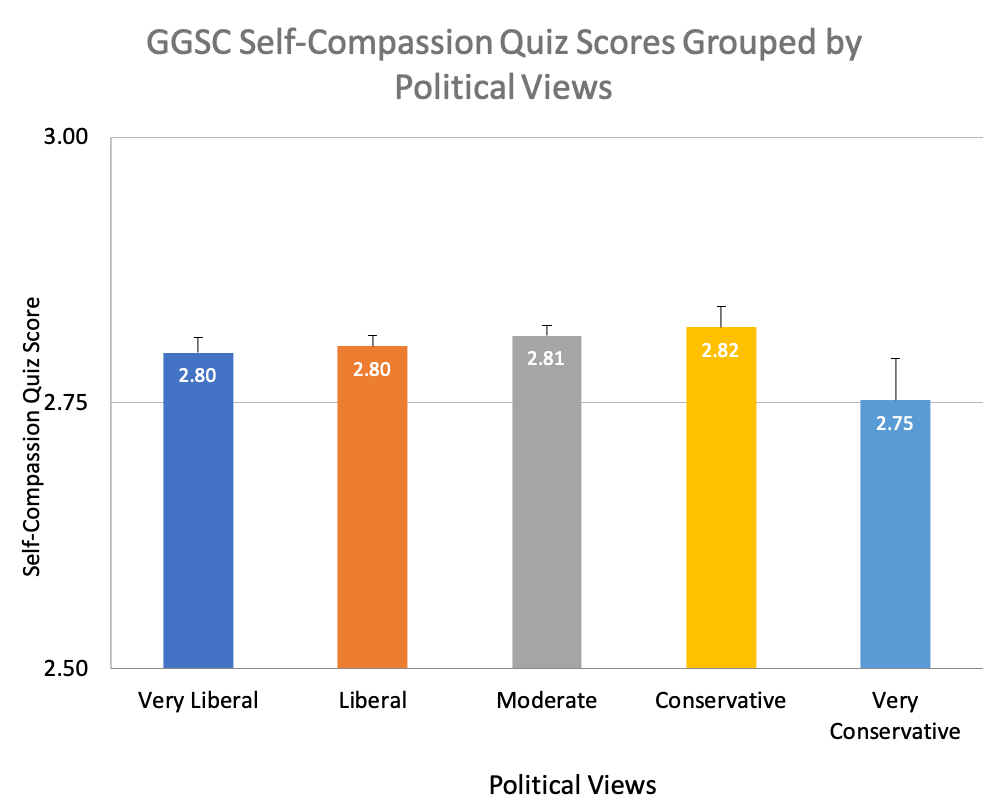

Your political views are not related to your self-compassion

In analyzing the results of other quizzes, we have found that political views can influence prosocial traits. For example, we found that political affiliations strongly influenced a willingness to build bridges with others; we also found that people with stronger political views had a stronger sense of purpose. In the case of self-compassion, however, we did not find a significant correlation with politics. Liberal and conservative quiz takers both scored very close to the overall average. Perhaps this is a point of common ground, and an opportunity for connection.

According to Neff, strengthening self-compassion involves prioritizing activities that boost awareness of mental experiences—in other words, mindfulness. This step helps us recognize mental barriers to self-compassion, like self-criticism, perceived social isolation, or antipathy. Self-compassion also involves efforts to highlight common humanity—one’s sense of connection, belonging, and social integration. The third step is to tap into and boost our innate drive to care and nurture, so that we can offer the supportive stance we spontaneously give to others to ourselves during hard times.

Could investing in all three dimensions of self-compassion help political opponents sidestep a sense of defeat or powerlessness? It’s an idea worth exploring.

Comments