By the time Josh and his cohort of U.S. federal mediators entered the negotiation room in Washington, D.C., what should have been a momentous occasion was a hot mess.

At a meeting between negotiators representing hundreds of Native American tribes and the federal government, dozens of people were angrily clamoring for seats. Assistants, advocates, lobbyists, attorneys, civil servants, and members of the public were also elbowing their way through the crowded negotiation room. It was a worst-case scenario for Josh and his colleagues, federal mediators tasked with resolving some of our nation’s most complex disputes.

For over 30 years, we’ve studied conflict and how it can go wrong. At the Morton Deutsch International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution, our wheelhouse is navigating tough disputes effectively. We lead research that promotes constructive conflict resolution and helps people work through wicked problems. And our research feels especially relevant today, in a world where even minor disputes—as well as major problems like COVID that in the past might have unified our communities—often become weaponized politically and trigger outrage and resistance in so many of us.

Ten years ago, we undertook a review of mediation studies that revealed a fragmented understanding of the best ways to handle conflicts that go off the rails. It came at the urging of the United Nations’ Mediation Support Unit, which wanted to arm its envoys with proven tactics to soothe difficult conflicts. So, we ran a series of new studies with expert mediators to unearth the major flashpoints that often spoil mediation efforts and keep conflict entrenched. We’ve since developed and tested strategies for navigating those derailers that can help community, business, and government leaders address them effectively and help people bridge differences.

Why some conflicts resist resolution

What causes mediation to fail? We group the derailers into four categories:

- Conflict intensity: high levels of conflict escalation, emotional volatility, destructiveness, or complexity. Picture mediating between two angry, irate, and resentful brothers over their long history of grievances.

- Constraints: mediation efforts that are greatly constrained by time, law, cost, or cultural mores. This is common in many settings, such as when mediating disputes involving foreign cultures, governments, or large multinational institutions such as the U.N. and the World Bank.

- Competition: when conflicts occur between people or groups who are solely competing for coveted scarce resources. Imagine mediating between two five year olds over the control of the only available garden hose on a hot summer day. The disputants view these as purely win-lose.

- Covert issues: when conflicts involve issues that prove difficult or dangerous to talk about openly. We see this a lot when mediating with families or in disputes between individuals with large differences in power, such as between managers and staff.

Once we understood what caused many mediations to fail, we asked Josh and other successful mediators for insights, and then used that feedback to generate a set of practical, evidence-based approaches intended to wrangle each of these challenges effectively.

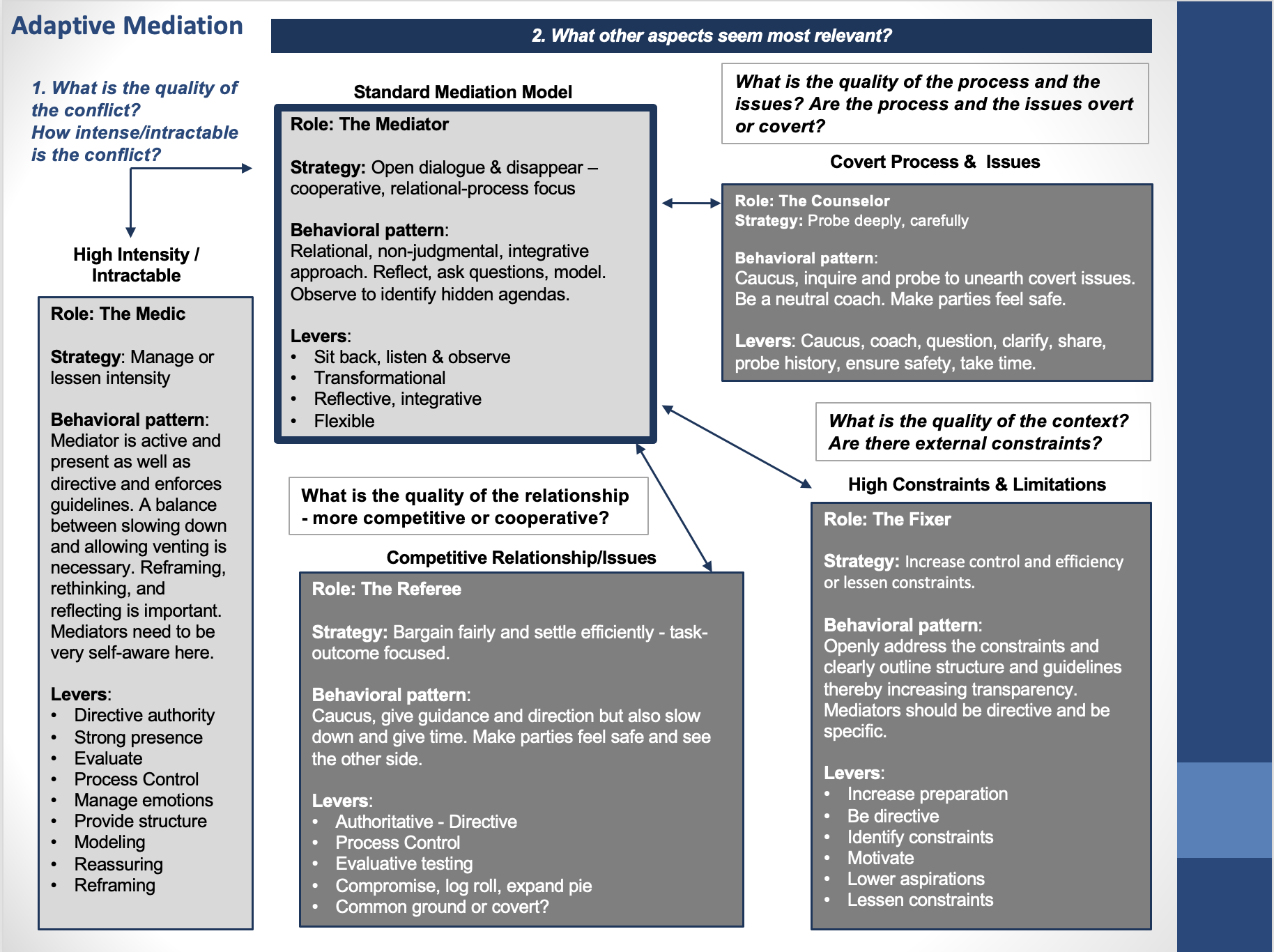

Turns out, each of these four tripwires requires mediators to step into a very different posture to limit the damage and get back on track. They include:

- The Medic: to triage the conflict and reduce heated spikes in intensity

- The Fixer: to manage highly restrictive situational constraints

- The Referee: to support firm, fair, and friendly process in all-out competition

- The Counselor: to carefully surface unexpressed concerns or hidden agendas

We think these four strategies can help to keep heads cooler, smooth negotiated interactions, and promote agreement. But first, let’s see how Josh and his colleagues tamed this breakdown between the federal government and the tribal nations.

Getting a discussion back on track

A bit of background: Two years before Josh and the other federal mediators faced that worst-case scenario of musical chairs, the tribes and the federal government had been deeply involved in talks about how to steer the largest federal transportation infrastructure investment on tribal lands in history. Transportation improvements—including road building, guardrails, and critical signage for safety in Indian Country—were badly needed. But development hit a wall in 2018 when federal staff charged with negotiating the rules arrived to a meeting having written them without regard for input from tribal negotiators.

Galled by the slight, and by the lack of respect in flouting decades of usual sovereign-to-sovereign dealings, tribal leaders pushed back. They refused to accept the rules, and the resulting clash led the tribes to ask Congress for federal mediators to break the impasse.

In the fall of 2018, Josh and his team had four days to begin to steer the program’s disastrous trajectory back on course. And they faced not one, but all four of the flashpoints:

- The conflict was high-stakes and passions were intense.

- The negotiations were extremely constrained by governmental bureaucracy and the need to respect tribal sovereignty.

- Each entity was competing for the most control over the details of the final program.

- Key policy issues weren’t being openly discussed.

To calm the initial tensions, federal mediators first took control of the room—a classic Medic move. They assigned the contested seats and gave priority to named negotiators over the rest of the assembled crowd. Then they established themselves as there to help shepherd a fair and functional process (Referee). They set up another, smaller table and let the larger group delegate authority to one named negotiator from each side to sit at it. This Fixer tactic helped to contain the chaos and cacophony of the process.

Josh’s team then assigned two mediators to help the smaller group identify, prioritize, and propose solutions to policy problems, many still unspoken (through Counseling). However, the larger group remained directly engaged through digital technologies that allowed them to weigh in on the priority of issues, which were immediately displayed and ranked on a large screen (aka, the Fixer). These steps lowered intensity, increased cooperation, and opened dialogue. Moving some subsequent meetings from Washington, D.C., to agreed-upon Indian Country locales helped address some of the needs for respect for both federal procedures and cultural traditions.

The trick in leveraging these flashpoints toward optimum success was not only in the specific techniques employed. Instead, much like controlling the center of a chess board, successful mediation is about knowing which of the flashpoints to address when and how. This is what we call adaptive mediation, which looks something like this:

How to use these mediation strategies in your community

You can help groups and individuals resolve conflicts in your family, community, business, or campus by employing a similar approach. For example, you might begin the process as a Counselor to build trust initially, especially if positions are deeply entrenched. If two parties disagree about politics—especially today—you might prompt them to begin by sharing their own stories about their personal experiences of the issues under contention, before jumping into a debate. This can help provide context for the discussion, and introduce a sense of mutual humanity at the onset of the talks.

If you’ve made some early progress, you might transition to Fixer in order to help the parties begin to reckon with the various constraints individuals and groups often face in trying to resolve disputes. If your employees are at odds over getting equitable recognition for their work contributions on a team, for example, the Fixer can bring them together to jointly develop a list of how their work may be set up to contribute to these tensions. Then, encourage them to take that list out of the meeting and work on finding solutions separately. After that, you could bring them together again to present their ideas to each other and discuss, while highlighting concepts they have surfaced that might help overcome the obstacles to their success.

High-stakes disputes will often benefit from a Medic approach early on to lessen the intensity of the conflict and enforce a level playing field in the face of power imbalances. This happened recently when a dispute between two brothers over their roles in the family business erupted into a near brawl. The mediator needed to immediately command the room—stand up, raise her voice, and caution the disputants about the possible consequences of going to blows. This helped. Then, when the sparks were contained, the mediator pivoted to Counselor to begin to help the brothers voice some of the deeper, hidden issues, often extremely personal, that were preventing resolution. She did this first in individual discussions with each brother, then brought them back together to talk.

You also might find it useful to serve as a Referee when it becomes clear that there are important tradeoffs and compromises that will need to be made in order to get to “yes.” A colleague of ours, Lela Love, used this strategy when mediating between the mayor of a small community and a group of day-laborer immigrants over their use of a public gathering space for seeking daily employment. After listening to lengthy monologues from the many parties to the dispute, Lela took control of the process and outlined the main issues as she saw them, and then welcomed comment. Once they reached consensus on the issues, Lela was able to first elicit their preferred remedies and then broker a deal between the disputants that they all could agree on. Although concessions had to be made by all sides of the dispute, the solution was ultimately constructive and empowering of the entire community.

The adaptive mediation approach was ultimately a winning formula for the federal mediators. After a rapid-fire series of in-person mediation summits (in Shawnee, O.K.; Scottsdale, A.Z.; and Cabazon, C.A.) that featured a delicate combination of larger-group and smaller-group mediated negotiation meetings, federal and tribal negotiators reached agreement on a 113-page document containing all the details of the new transportation infrastructure program—the largest pre-pandemic federal infrastructure investment for tribes in American history.

This is how we have found people can take advantage of what we’ve learned about conflict mediation flashpoints, and how to avert them. Key is knowing which four flashpoints to watch for, and devising strategies and skills for how to navigate or leverage each.

Editor’s note: This article was prepared by Joshua Flax in his personal capacity. The views and opinions expressed in this article are his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service (FMCS) or the United States government. References to the FMCS should not be construed as FMCS’s endorsement of any product, service, enterprise, or the material contained herein.

Comments