As a child, painter Paul Klee was fascinated by the vivid faces he saw in the swirly surfaces of the marble-topped tables in his uncle’s restaurant. As a pupil in school, the artist Salvador Dalí gazed up at the ceiling of his classroom, perceiving outlandish scenes in the stained plaster. And as a master offering advice to other creators, Leonardo da Vinci recommended that they look to clouds and rocks, among other natural formations:

If you have to invent some scene, you can see there resemblances to a number of landscapes, adorned in various ways with mountains, rivers, rocks, trees, great plains, valleys and hills. Moreover, you can see various battles, and rapid actions of figures, strange expressions on faces, costumes, and an infinite number of things, which you can reduce to good, integrated form.

These artists were engaging the human faculty of pareidolia: the tendency to perceive a meaningful image in a random or ambiguous visual pattern. Scientists are now exploring the connection between pareidolia and creativity; several recent studies have found that creative people are more apt to see pareidolias in the world around them than are less creative people. Assessing individuals’ capacity to recognize such patterns has even been proposed as a way to measure relative levels of creativity.

More interesting, I think, is what the phenomenon of pareidolia can tell us about the nature of creativity itself, and about how we can use this innate ability to help us imagine and create new things. A few thoughts:

Creativity isn’t just about thinking; it’s about seeing. The scientific study of creativity —and the popular understanding of it, too—often focuses on the conceptual aspect of creativity, the phase during which we’re coming up with ideas. But the creative process begins well before that, in the way we look at the world around us.

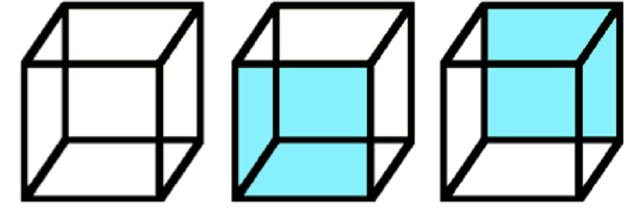

“Creative individuals seem to process external sensory stimuli differently, in that they will tend to more easily connect unrelated elements,” writes one team of scientists investigating the relationship between creativity and pareidolia. Research has found that creative people also exhibit higher levels of “perceptual instability.” When shown an optical illusion like the Necker cube (below), they are able to shift back and forth more readily between the two ways of perceiving the figure.

Creativity is about making meaning from the raw material of the world, using the capacities we have evolved as biological creatures. Scientists theorize that pareidolia is a product of our evolutionarily adaptive ability to distinguish faces and other meaningful images from the mass of visual information that meets our eyes at every waking moment.

This perceptual capacity is exquisitely tuned to the organic world in which we evolved; laboratory research finds that we are most apt to see pareidolias in scenes that display a visual complexity roughly equivalent to the scenes we encounter outdoors.

The perceptual equipment handed down to us by evolution is adapted to what is natural, and also to what is social and emotional: The images we are most likely to see in random patterns are faces—and often dramatically expressive faces at that.

Mirabeau, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Creativity is about tolerating, and making use of, ambiguity. The world is continually presenting us with images and experiences that are indeterminate, that don’t have a definitive meaning or explanation. Creative people seem to be able to linger longer in this space of indeterminacy, not rushing to assign a label or a conclusion, taking enough time to see all of what might be there.

A capacity to tolerate ambiguity allows us to reap its benefits, one of which is this: Ambiguity in the outside world draws out material from inside us—emotions and beliefs and memories of which we may not have been aware. When we are confronted with an indeterminate or incomplete stimulus, we ourselves supply the missing parts, and those parts are drawn largely from our unconscious. Pareidolias lead us to project our own internal “stuff” onto the world, making it visible to us and allowing us to work with it in a creative fashion.

These habits of mind are ones we can consciously cultivate. Here are three ideas for using pareidolias to enhance your creativity:

1. Actively look for pareidolias. Suggestive patterns can be found everywhere: in the natural world of clouds and rocks and tree trunks, and in the manmade world of cars and buildings and tools. For someone alert to pareidolias, everyday life is enchanted. There’s something benignly subversive about them, as if the universe is winking at us.

2. Attend to pareidolias in your own work. Creators who are masters of their craft are adept at spotting nascent and as-yet-unexplored patterns in their own drafts and sketches. I wrote this in The Extended Mind:

Researchers who have observed artists, architects, and designers as they create report that they often “discover” elements in their own work that they did not “put there,” at least not intentionally. . . . In one in-depth analysis of an experienced architect’s methods, researchers determined that fully 80 percent of his new ideas came from reinterpreting his old drawings.

3. Contemplate pareidolias as a way of easing yourself into a creative mindset. Engaging in pareidolia is itself a creative act: We’re perceiving something that doesn’t (yet) exist, which is the essence of creativity. At the same time, the beauty of pareidolias is that they are effortless and automatic: Our brains create them for us, using what the psychologist Alfred Binet called our “involuntary imagination.”

Research has found that spending time looking at ambiguous figures “primes” a creative mindset, inducing people to think with more fluency, flexibility, and originality. And no wonder: Contemplating pareidolias invites us to step out of a literal, cut-and-dried world where everything is exactly as it seems—into a world that is enigmatic, emotional, even fantastical.

Try entering the search term #pareidolias on Instagram; you’ll find thousands of evocative images. How about you? Have you ever been inspired by a pareidolia?

This article was originally published on Annie Murphy Paul’s Science of Creativity Substack. Read the original article.

Comments