How do you think a friend would rate the quality of your relationship with her? How would she describe you—as cheerful, compassionate, irritable, self-critical? Does that description match your self-image? How much does her perception of you matter to your happiness?

Those are questions we explored with students of the online Science of Happiness course. Students nominated “peers”—people they interact with most days—to (anonymously) answer questions about them and quality of their relationships. Students didn’t see the other person’s answers; we didn’t want to make friends insecure! The real purpose? To discover how relationships affect feelings of happiness.

GG101x co-instructor Emiliana Simon-Thomas

GG101x co-instructor Emiliana Simon-Thomas

We got responses from just over 2,500 peers, especially spouses (33 percent), friends (26 percent), and romantic partners (16 percent), with a smaller proportion of family members and a sprinkling of coworkers. Forty-five percent had known the student for more than 15 years, and 23 percent had been acquainted for one to five years.

The results are now in—and they confirm decades of research showing that if you want to be happier, then you should focus on the quality of your relationships.

For the most part, others see us as we see ourselves

First, results show that friends see the students pretty close to how they see themselves, which gives us confidence in the data. It may be true that people craft their public personas to appear more socially desirable, but these data suggest that we tend to more honest and authentic in our daily relationships. It would be troubling if students saw themselves as harmonious but romantic partners and best friends saw them as hostile.

Peers rated students on 32 characteristics, organized into thematically-matched pairs (e.g., dissatisfied/complaining, optimistic/hopeful). We ran what’s called a factor analysis to see if certain characteristics tended to show up together, and we discovered three different patterns, which we called personas:

- Positive: These folks were high in positive characteristics (happy/cheerful, content/satisfied, optimistic/hopeful) and low in negative characteristics (dissatisfied/complaining, anxious/stressed, self-critical/hopeless.)

- Pro-social: These students were different from those with positive personas, in that they focused on the well-being of others or of groups, by being compassionate/nurturing, cooperative/harmonious, or forgiving/generous.

- Anti-social: This persona tended to be irritable/agitated, hostile/argumentative, or distracted/absent-minded. Anti-social students are, according to peers, consistently negative or just not as interested in nurturing other people’s happiness—relative to other people in the course, anyway.

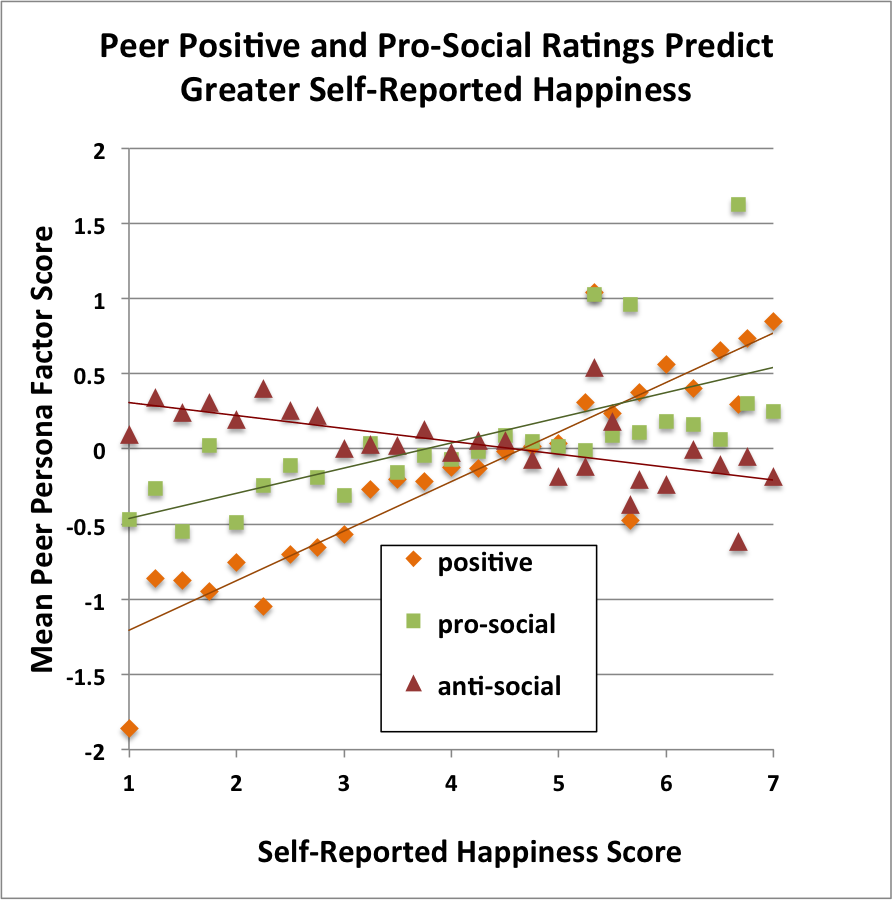

When we compared these scores to surveys that students filled out about themselves before the course began, we found that outer persona and inner lives do tend to match up. When friends said students were doing well, students were more likely to consider themselves happy. On a darker note, results also suggest that being anti-social—more irritable, argumentative, and disinterested—does not go unnoticed. Friends tune into anti-social behavior and describe us this way. What’s more, being seen as anti-social correlates with less self-reported happiness.

Positive and pro-social peer ratings of students predicted greater self-reported happiness scores. Peer anti-social ratings predicted lower self-reported happiness.

Positive and pro-social peer ratings of students predicted greater self-reported happiness scores. Peer anti-social ratings predicted lower self-reported happiness.

Focusing on others makes relationships exceptional

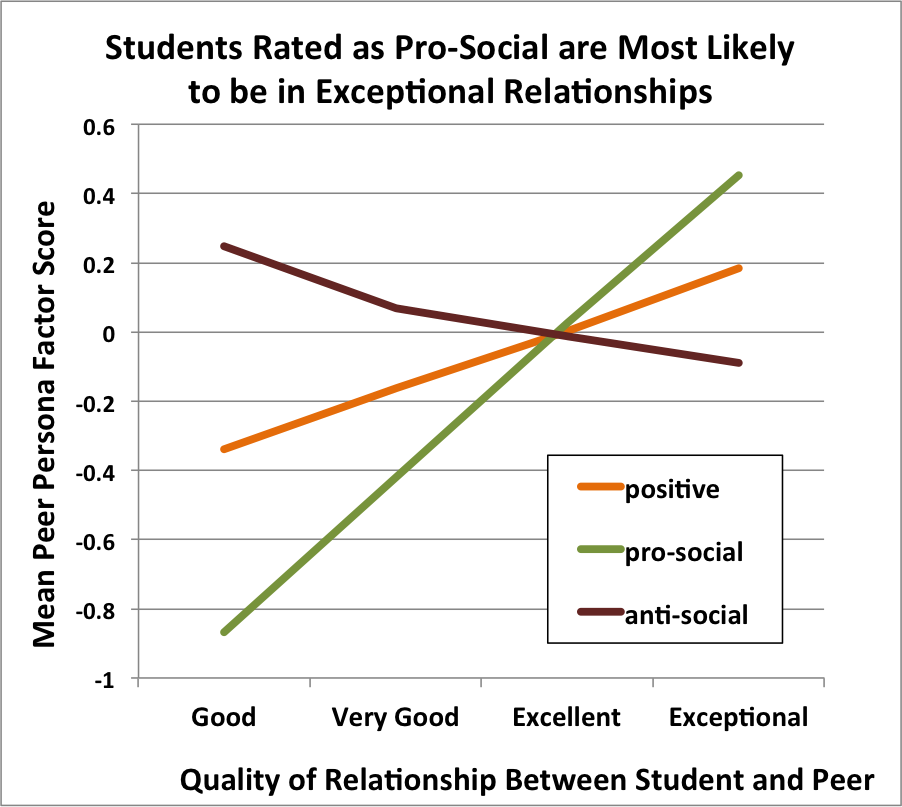

Results also show that the more kind, compassionate, cooperative, and forgiving friends said students were—in short, the more pro-social—the better they rated the quality of the relationships on a scale of 1-7, from poor (1) to exceptional (7). Positive people also had better relationships, even if they tended to be more self-focused than those who were rated as more pro-social.

Indeed, the greater a student’s positive and pro-social scores from their peer, the more likely their peer was to rate that relationship with our top score—an “exceptional” seven. Conversely, the more anti-social the student’s peer rating was, the further that peer’s relationship-quality rating drifted towards a four, or merely good. (Because very few peers rated their relationships as anything less than good, we excluded 1-3 scores from the analysis.)

What elevates a relationship from “excellent” to “exceptional”? Being more pro-social seemed to make the difference. Being positive is good. But being pro-social pushed relationship quality to the next level. And as we’ll see, relationship quality is what pushed up the student’s happiness scores.

Students with greater peer scores for positive and pro-social characteristics were more likely to have peers who rated their relationship as exceptional; this effect is strongest for pro-social. Students with greater anti-social scores were less likely to have peers who rated their relationships as exceptional.

Students with greater peer scores for positive and pro-social characteristics were more likely to have peers who rated their relationship as exceptional; this effect is strongest for pro-social. Students with greater anti-social scores were less likely to have peers who rated their relationships as exceptional.

Exceptional relationships make us happier

It’s a basic tenet of happiness science: supportive relationships are critical to well-being. Social relationships, to paraphrase Ed Diener’s formative 2002 study of “Very Happy People,” do not guarantee happiness, but happiness does not occur without them.

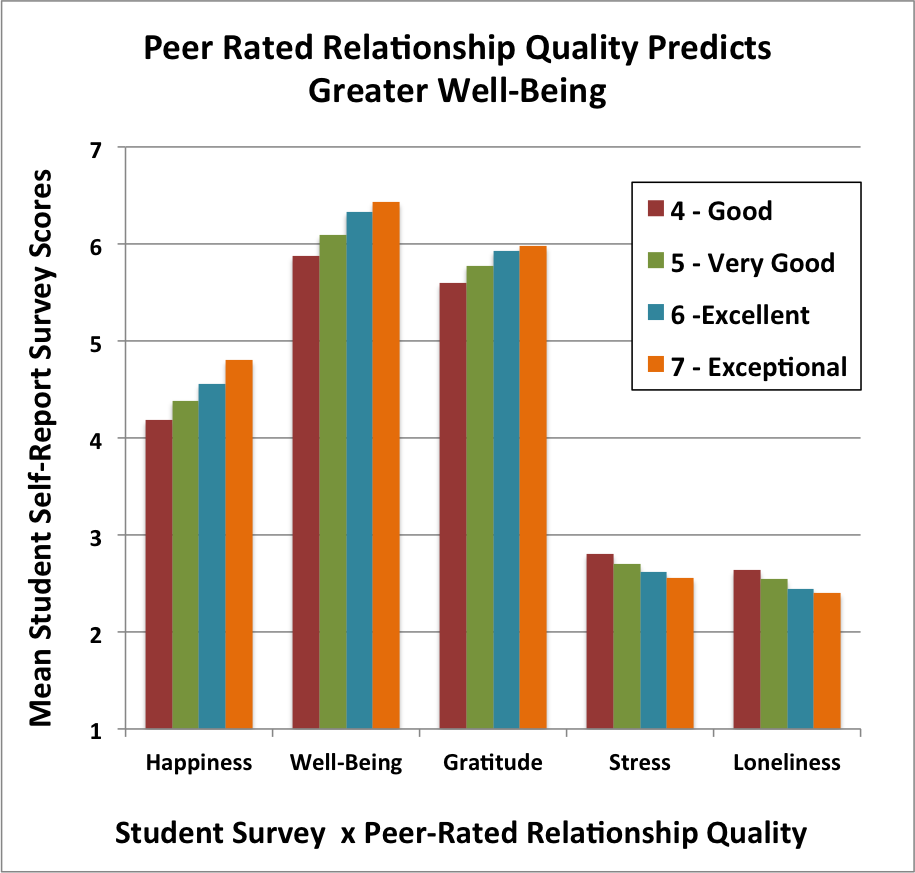

In our analysis, we looked at how the quality of relationships, as judged by peers, related to students’ own scores on measures of well-being. Very systematically, the data reveal increasing benefits to well-being in harmony with better-quality relationships, even for what might seem to be subtle differences between descriptors like “excellent” and “exceptional.” Wherever we looked, students who were in exceptional relationships were faring better.

Students’ self-reported measures of well-being increasingly improve with better ratings of relationship quality from peers.

Students’ self-reported measures of well-being increasingly improve with better ratings of relationship quality from peers.(Caveat: this analysis is correlational data, which means that peer input does not cause happiness scores. In fact, the reciprocal explanation is just as valid: peers of happy people tend to rate them as more positive and pro-social while peers of less happy people rate them as more anti- or even asocial.)

Introverts can have exceptional relationships, too

“Sure, this is all fine and good,” say many students, “but what about introverts?” By definition, they’re not as socially outgoing as other people; they’re not motivated to be the center of attention. Does that mean out-going extroverts, who have an easier time approaching and engaging with other people, are just going to have better relationships?

Not necessarily. We explored whether extraverts were more likely to be in exceptional relationships, and the answer is no. Extraversion was not linked to higher or lower relationship ratings; introverts are just as good at exceptional relationships as extraverts. And because it’s the exceptional relationships that make us happy, this suggests that introverts can find fulfillment through them.

We can all make our relationships exceptional

Of course, introversion is not the same as being anti-social. What about the relatively anti-social people—is there any hope for them?

Our online course, The Science of Happiness, provides the scientific basis for recognizing innate pro-social capacities like empathy, kindness, compassion and gratitude—and the course supports real-life cultivation of pro-social skills through weekly research-tested happiness practices. This is a path available to everyone, no matter where they’ve started.

Ultimately, our analysis suggests, being more pro-social—engaged in meaningful, authentic relationships, showing kindness and generosity in the world and being part of a supportive community—is the most promising route to sustainably increasing our well-being. As GGSC fellow Brett Ford’s research suggests, this kind of approach to pursuing happiness may work better than striving for continuous pleasure, success, and power approach to happiness.

But first, you have to actually try the practices. We have found that people who complete The Science of Happiness show immediate and sustained boosts in well-being.

Some may think we’re stuck at where we land on a happiness scale, but our brains change over time with repeated experiences, both internal and external. In short, the three personas we’ve identified do not represent fixed or absolute qualities. Even if you suspect you are on the anti-social end of the spectrum, the opportunity remains to discover and strengthen your relationships—and, therefore, your happiness.

Comments