Why do more than 70% of middle and high school students in the United States feel like schools are uncaring environments, and 70% of the public believe that more things about the educational system should change than stay the same? This is likely because the structure and function of schools have not evolved much over the past 100 years, even as the needs of students and the knowledge and skills demanded by the economy are dramatically different.

There are high schools that work well for all students and educators. They are the exception, but they exist, and we can learn from them. Unlike century-old schools operating under the industrial model of schooling designed to prepare the majority of students for rote work, these redesigned high schools are developed based on a large and growing body of modern research from the fields of neuroscience, psychology, and other developmental and learning sciences known as the science of learning and development.

Our growing understanding of this science makes it clear that young people grow and thrive in environments designed to support individualized development, where they have strong, supportive relationships, and where their social, emotional, physical, and cognitive needs are met.

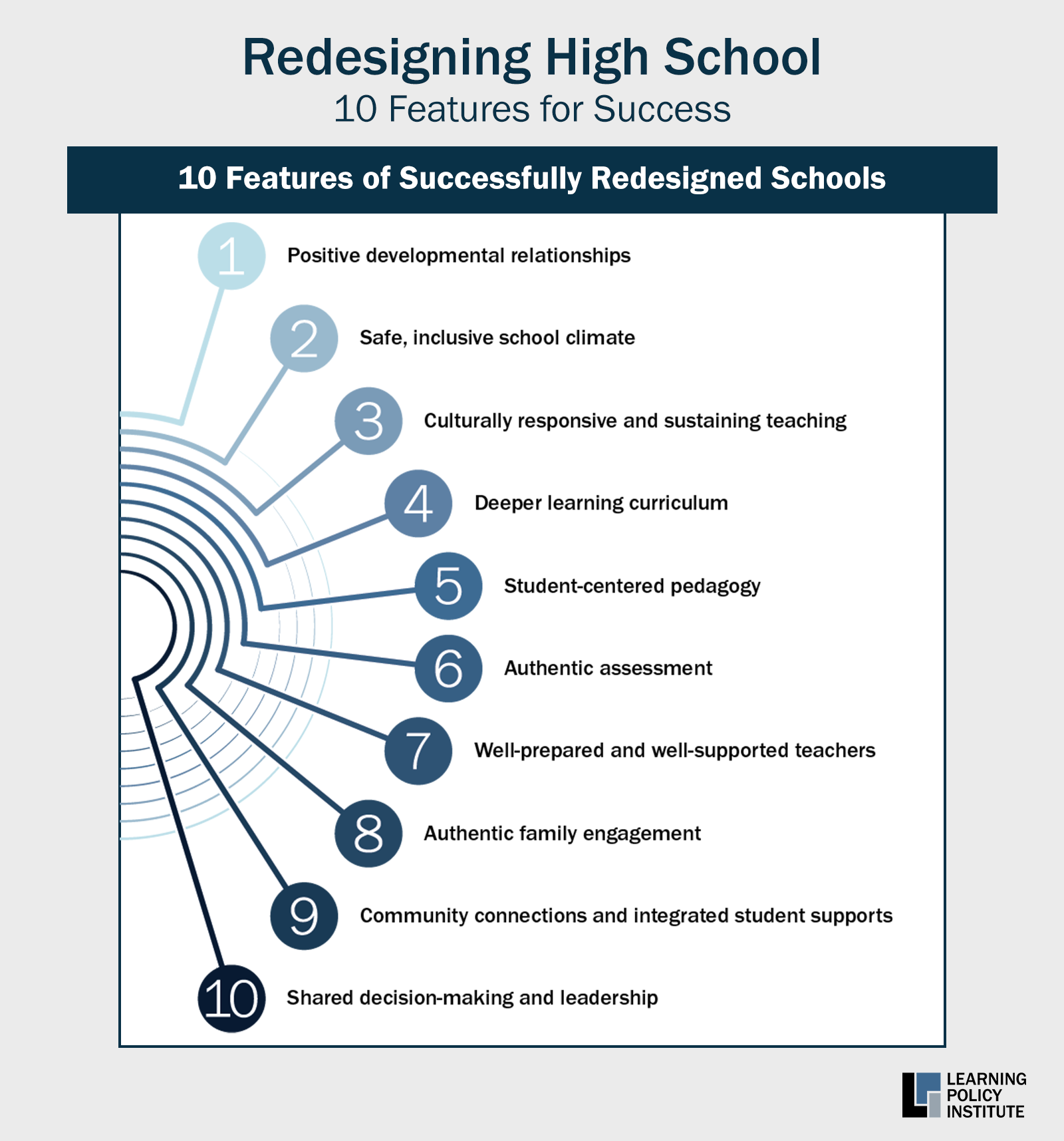

A recent Learning Policy Institute (LPI) publication that one of us coauthored, Redesigning High School: 10 Features for Success, highlights the evidence-based features of successfully redesigned schools that help create the kind of education many of us want for our children:

Below are three of the 10 features, all related to socio-emotional development, and examples of schools that have successfully implemented them.

Positive developmental relationships

Healthy and supportive relationships are the key to brain development, and research suggests that students thrive and learn best when their teachers know them emotionally and intellectually. However, creating the conditions for strong, developmental relationships means rethinking the prevalent factory-model school design where students move from one overloaded teacher to the next in 45-minute increments and receive numerous disconnected lessons daily. Effective schools are structured to support both building strong relationships and allowing them to develop further over time.

LPI’s report shares examples of these practices, including creating smaller learning communities, sometimes called “houses” or “academies,” within larger schools. These communities allow the same group of students to work together over multiple years. Another approach involves implementing structures for building stronger relationships over time, such as “looping,” where teachers stay with a cohort of students for multiple years, building strong relationships and a community balanced by trust, structure, fun, and mutual accountability.

Oakland International High School uses looping, along with cohorts, to support its diverse students, many of whom are new immigrants. An interdisciplinary team of four core-content-area teachers stays with a group of 80 to 100 students for two years (looping). In addition, the school assigns each ninth grader to an advisor—usually a teacher, but sometimes a school leader or other staff (for example, a counselor). Advisors and the interdisciplinary team of teachers work with the students for two years before they transition responsibilities to other staff who will work with the students for 11th and 12th grade. These looping and advisory structures have been especially important to the success of international schools, as they enable practitioners to provide personalized support to students who have a wide range of needs.

Another key element for building stronger teacher-student relationships is advisory systems, where groups of 15 to 20 students are placed together with a faculty advisor several times a week for ongoing academic and personal counseling and support. These advisory teachers advocate for their students and often serve as their advisees’ main adult point of contact. They gather information from other teachers about the young people’s needs and spearhead efforts to support them. Advisory teachers also build and strengthen relationships with families.

At Bronxdale High School in New York City, all students have an advisory class several times a week with activities that support social and emotional learning, academics, college and career readiness, and community building. Sometimes students strengthen academic skills like note-taking and critical reading strategies, and other times they explore opportunities for after high school or build a strong learning community while exploring essential questions: Who am I? What do I have to contribute? How can I impact my community? One guidance counselor explained, “Advisory is where the safe, supportive culture starts and then spreads through the whole school.”

Safe, inclusive school climate

Strong positive relationships between educators and students are necessary, but for students’ full learning potential to be unleashed, they need to be in an environment that is both physically and psychologically safe, calm, and consistent—a place where they can experience trust and belonging, so they can take risks and thrive. Brain science reveals how important safety, predictability, and support are to learning. This is even more critical for youth who have marginalized identities or who have experienced trauma. When our bodies or identities feel threatened, the brain becomes flooded with cortisol, which undermines cognitive capacity and short-circuits learning.

Effective schools work proactively to create environments where all students feel safe and included. They are explicit about their school’s norms, expectations, and values. Traditional school practices, which often privilege a certain type of knowledge and sort students by these narrow definitions of ability, need to be transformed through community building, developing shared values or dispositions, and explicitly teaching social and emotional skills. Research finds that students who participate in social and emotional learning programs show improvements in their collaboration and problem-solving skills, as well as attitudes about themselves and school.

Teaching empathy and skills for recognizing emotions and resolving conflict peaceably, commonly called restorative practices, are cornerstones of a safe, inclusive school climate. In traditional high schools, disciplinary practices often differ from teacher to teacher, and the school is governed by strict rules and harsh punishments that often exclude students from instructional learning time through suspensions and expulsions and cause many young people to disengage. In restorative high schools, students are enabled to resolve conflicts and make amends through community-building activities, restorative counseling, and re-entry circles.

For example, in these settings, restorative practices such as community circles are held regularly. Students share what happened in a conflict, what role they played, and what could be done to make things right. In a conversation about circles, a student at Ralph Bunche Academy in the Oakland Unified School District in California—who had been expelled from his previous school—shared, “After two weeks [of community-building circles at my new school], I realized it was the first time in my life I ever wanted to be at a school! Like ‘We got circle today, I gotta go!’ I wanted to be in class, do projects, interact, be one of the first students called on. I felt good being up here!”

This video about Restorative Circles at Fremont High School in Oakland, California, shows that circles can be a preventative tool through community building, a mediation tool for conflict, a support tool (as in a grief circle), or a strategy for intervention.

Culturally responsive and sustaining teaching

Another aspect of creating an educational community in which young people can thrive and learn is ensuring that all students feel valued and seen for who they are. This requires an explicit commitment to culturally responsive and sustaining teaching, which promotes respect for diversity and creates a context within which students’ differing cultural experiences can be understood, appreciated, and connected to the curriculum.

Too often, students can feel dehumanized by their school’s culture, curriculum, or practices. In United States schools, there have been increased threats to students’ social identities (identities related to race, ethnicity, language background, immigration status, family income, gender, sexual orientation, or disability, among other things), creating toxic stress that undermines student engagement and learning. Educators must be intentional about the school environments they create and establish an environment where all students feel welcomed and safe to bring their multiple identities and experiences to the classroom and curriculum.

Culturally responsive and sustaining pedagogy requires teachers to learn about and with students and families. These practices are not simply designed to build esteem in learners, as Zaretta Hammond establishes in Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain; the strategies support information processing so students can engage in rigorous intellectual work. Creating supportive and collaborative learning environments leads to increased safety and intellectual engagement, especially when paired with relevant instructional tasks and assessments that have application to life outside of school. Hammond’s blog serves as a companion to her book, providing real-world examples of how to develop cultural competence and strategies to shift the mindsets of teachers and learners.

Social Justice Humanitas Academy (SJ Humanitas), a small neighborhood high school located in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles, serves primarily Latino/a students (96%) from low-income families (93%) and has a 97% graduation rate, which far exceeds that of the district and state. SJ Humanitas takes a culturally responsive approach to its curriculum by centering the experiences and strengths of the Latino/a community and other marginalized groups so students can develop a sense of identity and confidence that supports their perseverance and success.

A teacher who grew up in the community explained that she remembered “thinking about how ‘ghetto,’ or ugly, or dirty my community was, and just thinking about all the negative aspects of my community. What we’re trying to do is . . . flip that, and we’re trying to come from an assets-based understanding of our community, and what our kids bring to school, what our parents bring, and instead of focusing on all the negative things, we want to focus on the positives and how can we use those to help propel us forward.”

LPI’s Redesigning High School report provides further details, examples, and tools for these three practices, plus seven additional: deeper learning, student-centered pedagogy, authentic assessment, well-prepared teachers, authentic family engagement, community connections, and shared leadership and decision making.

Although redesigning high schools for personalization can be challenging, it is essential if we want all students to learn to their full potential. As a student at Vanguard High School in New York City (a member school of the New York Performance Standards Consortium) reminds us, “School should not be mass production. It should be loving and close. This is what kids need; you need love to learn.”

Comments