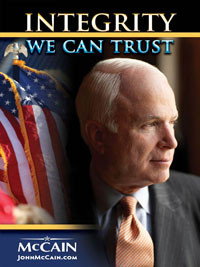

High-stakes democratic elections often boil down to a matter of trust. In this year’s presidential race, for example, junior senator Barack Obama has routinely peppered his speeches with “you can trust me on that,” or, “so you can trust me when I say….” Meanwhile, veteran senator John McCain has tried to convince Americans that he has “earned” their trust.

“Trust is uniquely and especially prominent this year because it’s an issue that rings so loudly when you talk about experience versus inexperience,” says Democratic strategist Jake Maguire, who has worked on campaigns for John Kerry, John Edwards, and Obama.

© Library of Congress

© Library of Congress

On the campaign trail, Maguire says, candidates often swap the suits and ties they wear at speeches and debates for rolled up sleeves and jeans. “Out there on the stump, the best way to look trustworthy is to seem like you’re ‘one of us,’” says Maguire. “The idea is: You can trust them. They’re just like your neighbors, the people you know.”

Indeed, political operatives have worked since the dawn of democracy to make candidates look trustworthy—an effective strategy, according to cutting edge studies that may change the way we view campaigns and elections. In recent years, researchers have found that snap judgments of candidates, based on nothing more than their faces, can reliably and powerfully predict the outcomes of political elections. According to these studies, it only takes a tenth of a second for subjects to decide if a face is trustworthy or not.

That means that despite the many appeals to voters’ values, interests, and policy positions, the outcome of this year’s historic presidential election may hinge on something that operates under the radar of human consciousness. “We make these rapid judgments from facial appearances whether we like it or not,” says Princeton psychologist Alexander Todorov, a pioneer in the study of first impressions. And that, it turns out, may be a serious problem for political elections.

Gut reactions

In a series of experiments, Todorov and his colleagues have revealed the political implications of our gut instincts.

In one 2006 experiment, they gave participants small amounts of time—100 milliseconds, 500 milliseconds, and 1 second—to judge if a face was trustworthy. The researchers discovered that decisions made after 100 milliseconds were highly consistent with decisions made with longer time constraints, suggesting that only a very brief time period is necessary to make a lasting evaluation. In other words, beyond those first 100 milliseconds, additional time for reflection doesn’t appear to change first impressions.

Todorov and his colleagues went on to study how these split-second verdicts might inform our political decisions. In several studies in 2007, the investigators presented participants with photographs of the winner and the runner-up of a senatorial or gubernatorial election. The researchers made sure participants didn’t recognize the candidates or know which one was the winner, then they posed a simple question, “Who is more competent?”

© david J. & Janice L. Frent Collection

© david J. & Janice L. Frent Collection

The results: After only 100 milliseconds of exposure to the faces, participants chose the winning candidate for about 72 percent of the Senate races and 69 percent of the gubernatorial races. In other words, gut instincts were highly consistent with actual votes cast after many months of supposedly rational deliberation. Predictions were as accurate after only 100 milliseconds of exposure as they were after 250 milliseconds and an unlimited amount of time. In fact, when subjects were instructed to take their time and think carefully, their responses were less consistent with real electoral outcomes than the snap judgments were. What’s more, judgments of competency were highly correlated with the margin of victory: the higher the facial competency rating, the higher proportion of votes that candidate received in the real election.

It’s as if all the debates, stump speeches, and TV advertising hardly mattered more than the immediate effect of a candidate’s physical appearance.

“I was fairly surprised by the initial data,” says Todorov. “We used a single slice of information, yet it did pretty well predicting a sizable proportion of the elections.” And, he adds, “we replicated the main findings several times before I was sure that the phenomenon was real.”

Todorov’s results are echoed in other researchers’ studies as well. In a 2006 experiment, for example, economists Daniel Benjamin and Jesse Shapiro asked participants to view silent 10-second clips of political debates. Despite not hearing the content of the debate, says Benjamin, “People were remarkably accurate in predicting the election outcome based on just watching these video clips.”

Economists have long noted strong correlations between economic conditions and the winners of political elections, with incumbents often benefiting from a solid economy, for instance. But for the first time, this study revealed an even stronger correlation between these rapid judgments and election outcomes. In other words, if you want to predict who’s going to win an election, giving people a split second to choose a face will yield an answer at least as accurate as one based on an analysis of the state of the economy.

© Library of Congress

© Library of Congress

Other surprising aspects of Benjamin and Shapiro’s study also seemed to confirm Todorov’s findings. For example, participants’ predictions were actually less accurate when the sound was turned on. Benjamin speculates that the audio distracted participants from their first instincts and led them to make decisions based on assumptions about who wins elections. In predicting electoral outcomes, argues Benjamin, “They would have been better served by going with their gut reactions.”

The trust reflex

The inclination to make snap judgments almost certainly has deep evolutionary roots. Neuroimaging studies reveal that trust evaluations involve the amygdala, a brain region responsible for tracking potential harm—something that probably came in handy on the prehistoric African savanna, where judging trustworthiness in a split second could well mean the difference between life and death. From an evolutionary standpoint, suggests Todorov, rapid detection of trustworthiness may be essential for survival.

Indeed, a growing body of literature in social psychology reveals that we need only small bits of information—so-called “thin slices”—to effectively navigate a complicated social world. Many of these studies find that with very limited exposure to social cues, subjects are remarkably accurate in a wide variety of judgments and predictions—a useful skill in a crowded urban environment, or one cluttered by the TV, radio, and Internet.

For example, research by social psychologist Dave Kenny has repeatedly found that it takes only a brief period of observation—and absolutely no speech at all—for strangers to accurately gauge the personality traits of one other.

Study participants’ assessments of strangers, based only on non-verbal cues and facial appearance, are remarkably consistent, and similar to how the individual assesses himself.

© McCain Campaign for President

© McCain Campaign for President

But when it comes to rapid judgments of which candidate to trust, it’s not clear that our gut reactions effectively steer us toward the person who’d actually do the best job.

To some, this line of research might call the whole democratic process into question. If people are voting based on split-second impressions, what’s the point of debates or any deliberative activity designed to appeal to rational decision-making? Why not just cut to the chase and vote for candidates based on their faces instead of their voting records and policy positions?

The best answer might be that rational thoughts and gut feelings exist in a never-ending conversation with each other. Gut reactions are important—but so is political information. Rational and irrational processes likely combine to shape citizens’ voting behavior.

Milton Lodge, a political scientist at SUNY Stony Brook, studies “hot cognition”—the idea that all thoughts have an emotional dimension. “The idea of thinking without feeling, making judgments without affect, is essentially impossible,” he says.

This means that those early impressions probed in Todorov’s studies probably influence the way we think about candidates later on—even when we consider our thought processes to be quite rational. According to Todorov, initial impressions of a candidate’s face can even color how we perceive that candidate’s performance down the line.

But while we can’t escape our automatic reactions, there may be ways of moving beyond them. Given enough accurate information, says Todorov, “people will change their minds.” In one of the Princeton studies, for instance, subjects made rapid character judgments based on facial appearance, then were given additional information in subsequent phases of the experiment. When participants were told that someone they had initially found trustworthy had robbed someone else, they had no problem changing their minds.

Of course, in the real world, we don’t often get such unambiguous information. But these results suggest that we’re not entirely locked into our first impressions. The researchers agree that while snap judgments might bias our evaluations, they don’t completely dictate our ultimate decisions. In order to gain more conscious control, “you get people to focus their attention on what’s important to them,” says Lodge.

© Obama Campaign for President

© Obama Campaign for President

How can we focus on what’s truly important when automatic reactions appear so hardwired?

Maguire suggests that one way to circumvent the power of first impressions is to think about the issues first and the candidate second. Many Americans learn about relevant social issues from the candidates themselves, he says, and are thus vulnerable to the emotional and visual appeals—or faces—associated with the information’s delivery. “If candidates define the issue for you, chances are you’ll agree with them,” he says. “So a smart way to get around that is to know your issues first, come up with some questions, and go see what the candidates have to say.”

Republican strategist Nino Saviano says it’s possible to temper emotional impulses through rational processes. “Interaction is key,” he says. “When candidates engage voters, they move past initial superficial considerations and voters look deeper into a candidate’s other qualities.”

Todorov agrees that with deliberate interaction and reflection, we can reign in at least some of our early emotional biases. “When people have opportunities to interact with the person they are judging, it is possible to overcome initial faulty impressions,” he says. “It’s most problematic in contexts in which people don’t have such opportunities.” The researchers and strategists agree that in the case of democratic elections, it’s often up to the voters themselves to seek out those kinds of opportunities.

Decision 2008

Political strategist Jake Maguire says the research on snap judgments resonates with his experience in the field. “There’s no doubt that a candidate’s appearance is often a deciding factor in how people come to think of him,” he says. And according to Maguire, both the Obama and McCain camps are keenly aware of this issue.

“John McCain has tried to undermine the public trust of Barack Obama by playing on the same concerns members of the public may have when they look at Obama,” he says. (Indeed, much research suggests that people have automatic, unconscious biases against those of a different race, which could potentially hurt Obama even among voters who wouldn’t explicitly consider race a factor in their vote; for more on this subject, see Greater Good’s Summer 2008 issue on prejudice.) Similarly, when Obama suggests that McCain has been inside Washington politics for too long, he’s playing on the initial impression some voters get from looking at McCain—that he’s too old.

Of course, we can’t say for sure how the candidates’ faces have affected the course of this election. But the importance of gut reactions and trust is clear. “When you look at polls, it’s never, ‘Who has a better plan on the economy?’” says Maguire. “The word is ‘trust.’ The question is always: ‘Who do you trust more to manage the economy? Who do you trust more to effectively prosecute the war in Iraq? Who do you trust more on health care?’”

So when Americans head to the polls in November, will that trust be rooted in first impressions, or will it instead be tied to something of more substance? Todorov says he doubts that facial appearance affects citizens who identify strongly with a given political party. But, he says, the powerful influence of a candidate’s face “likely affects a small proportion of voters who are the fairly uninformed voters, the swing voters, the undecided voters—and these are ultimately the people who decide most close elections.”

Economist Daniel Benjamin stresses that first impressions may not, in fact, be a problem at all. It’s entirely possible, he says, that people’s first impressions pick up on qualities that are important in a leader. “We don’t know if it’s something we want to overcome,” he says. “We don’t know if it’s good or bad.”

So how should voters make sense of this research as they prepare for this or future election days?

“What this line of research ultimately comes down to is that these emotional appeals are very powerful,” Milton Lodge says, “but it’s not that you can’t override them.”

Maguire agrees. As one way to temper emotional influences, he recommends reading the news instead of watching it. “We underestimate how much the way a candidate says something affects the way we hear it,” he says, “but it’s really remarkable.”

Ultimately, Maguire suggests, it takes real commitment on the part of the voter to make an informed decision. “It’s really about time. It takes more time to read than to watch TV. It takes more time to think about something,” he says. “But the truth is that if you want to make a rational decision, you have to come to that yourself. You can’t let a campaign give it to you.”

Comments

“The inclination to make snap judgments almost certainly has deep evolutionary roots. Neuroimaging studies reveal that trust evaluations involve the amygdala, a brain region responsible for tracking potential harm—something that probably came in handy on the prehistoric African savanna, where judging trustworthiness in a split second could well mean the difference between life and death. From an evolutionary standpoint, suggests Todorov, rapid detection of trustworthiness may be essential for survival.” I agree with this statement wholeheartedly!

Easytether | 1:55 pm, January 4, 2012 | Link

“But when it comes to rapid judgments of which candidate to trust, it’s not clear that our gut reactions effectively steer us toward the person who’d actually do the best job.” I agree with that. Often times though the “best” candidate for the job turns out A LOT different than we expected once he gets into office….

Pictures of Jesus | 2:00 pm, January 4, 2012 | Link