This month, Greater Good features videos of a presentation by Sonja Lyubomirsky, a leader in the field of positive psychology and an expert on the science of happiness. In her talk, Lyubomirsky reveals the many benefits of cultivating happiness, and offers research-tested tips for doing so. Here, she discusses a key insight from her research—which backs up some ancient wisdom.

There’s a famous Chinese proverb:

If you want happiness for an hour, take a nap.

If you want happiness for a day, go fishing.

If you want happiness for a month, get married.

If you want happiness for a year, inherit a fortune.

If you want happiness for a lifetime, help somebody else.

Notice the wisdom of this proverb. The first two things are just momentary pleasures—obviously, they are not going to make you happy forever. Getting married and inheriting a fortune are major circumstantial changes in life, but those are the kinds of changes people tend to adapt to over time—you get used to a new level of happiness, or a new level of wealth, and then you want more; that’s part of human nature.

In fact, when two colleagues, Ken Sheldon and Dave Schkade, and I conducted research into the factors that determine our levels of happiness, we found that only 10 percent lies in our life circumstances.

© © Ariel Duhon

© © Ariel Duhon

A lot of people are astonished to see that number being so small. They think: “Oh, I’ll be happier when I get a new job. Or when I get a boyfriend. Or when I have a baby.” But the truth is, those things don’t affect our happiness as much as we think they will.

However, our research has shown that up to 40 percent of our happiness depends on our behavior and daily activities—that’s 40 percent that’s within our power to change every day. (50 percent of our happiness is dictated by our genes—a high percentage, but not as high as we sometimes think.)

And when it comes to pursuing activities that can boost our happiness, the proverb gets it right: helping someone else is a surefire strategy. Studies that I and others have conducted show that practicing kindness generates significant increases in happiness.

In one of these studies, we asked college students to do five acts of kindness per week over a period of six weeks. Each week, we asked one group of students to do all five of their acts of kindness in one day; another group of students could spread out their acts of kindness over the entire week. And a third group of students (a control group) didn’t do anything at all.

The acts of kindness they performed ranged from the profound to the mundane. Here are some of the examples they cited:

- Bought my brother a comic book

- Donated blood

- Bought a homeless man a Whopper

- Visited Grandma in the hospital

- Was designated driver for a night at a party

- Helped someone (a stranger) with computer problems

- Told a professor “thank you” for his hard work

Obviously, people define “acts of kindness” differently, and there are a lot of cultural differences in this area. I once showed this list to an audience of people from different cultures, and they were horrified: “Visiting Grandma in the hospital is an act of kindness?” they said. “That’s your duty—something you’re expected to do.”

But I think we all can identify what we ourselves consider “kindness,” and try to do more of it. (My own goal for kindness, at which I am not very successful, is being nicer to telemarketers. Clearly, we all have our own subjective definition of what constitutes kindness.)

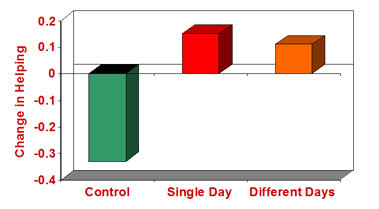

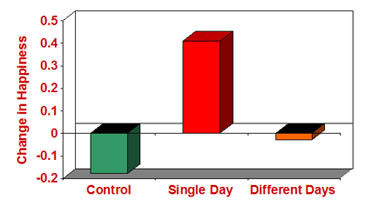

In our study, we found that members of the control group, who weren’t asked to help others more, actually helped less over the course of the study. But the participants who were asked to do those five acts of kindness a week—either on a single day or over a week—actually did report increases in helping.

What’s more, all that kindness did succeed in making them happier—but only in the condition where the students performed all their acts of kindness in one single day. I think that was because their acts were mostly pretty small, and it was more powerful to have them be more concentrated in a shorter timeframe. Spreading the acts of kindness across the week just might not have made those acts as distinguishable from the other things the students tended to do.

Why might kindness have these kinds of effects on our happiness? I believe that when you are kind and generous to others, you start to see yourself as a generous person, so it’s good for your self-perception. Plus, it helps you see yourself as interconnected to others, it makes you interpret other people’s behavior more charitably, and it relieves distress over other people’s misfortune—all things that are good for happiness.

Perhaps the biggest happiness boost comes from the social consequences of kindness. When you help others, you might make new friends, or other people might appreciate what you’ve done, so they might reciprocate in your times of need.

I’ve come to conclude that helping others leads to a cascade of positive social consequences: Lots of good social things happen when you are generous and kind to others, and many of these play a direct role in making us happier.

Comments

happiness is different for everybody… helping others not always makes me happy..

Mac-How | 2:43 am, July 26, 2010 | Link

That’s not the case with me.

I’m always happy whenever there is an opportunity to help someone.

usb sound card | 10:04 am, December 16, 2010 | Link

The conception of happyness differs from person to person. But I agree on the fact that If you help someone else being happy, you’re going to be happy yourself. Together we can all feel happy.

external sound card | 5:46 am, June 14, 2011 | Link

happiness is different for everybody… in the real

time.

all feel happy!

tarjetas de visita | 6:54 am, January 22, 2012 | Link