Asi Burak, a former Israeli Army captain, has intense green eyes and a serious, thin-lipped smile that can spread out into an impish smirk. After serving in the army, Burak received an art degree in Tel Aviv, then worked as an art director for Saatchi & Saatchi Advertising before becoming the chief designer and vice-president of a high-tech startup. He was successful in the corporate world, but he was restless. He wanted to do something more creative, “something different.”

So two years ago, Asi Burak came to Carnegie Mellon University, located in Pittsburgh, to study at one of the United States’ only graduate programs in “entertainment technology”—a program that combines video game design, computer animation, robotics technology, and dramatic story telling. Burak had his sights set on becoming a video game designer, but he did not want to create games that glorify cartoonish and brutal violence, like the best selling Grand Theft Auto. Instead, he had a radical idea: to develop “a serious game—something that promoted peace, not violence.”

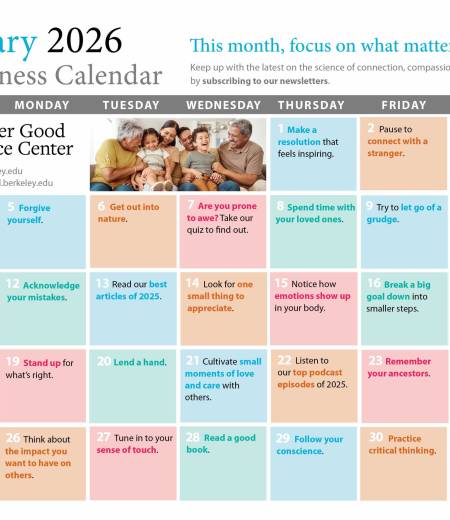

PeaceMaker video game co-producers Asi Burak (left) and Eric Brown (right), with Laurie Eisenberg, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University who has served as an advisor on the game

© Ken Andreyo

PeaceMaker video game co-producers Asi Burak (left) and Eric Brown (right), with Laurie Eisenberg, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University who has served as an advisor on the game

© Ken Andreyo

Burak receives feedback on PeaceMaker from a student who tested the game in Qatar

© Olive Lin

Burak receives feedback on PeaceMaker from a student who tested the game in Qatar

© Olive Lin

For the past two years, Burak has been leading a team of classmates to create a game called PeaceMaker, in which the goal is to create peace between Israelis and Palestinians.

“We chose the Israeli-Palestinian conflict partly because of my background as an Israeli Jew, but also because of the challenge that such a conflict presented,” he said. “It was one of the best examples of a serious conflict that we could think of.”

Burak and his colleagues pitched their idea of a game about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to their faculty advisors in the fall of 2004. As they anticipated, the proposal met with harsh skepticism. The faculty doubted the viability of such a game, as well as the students’ ability to complete their game design in a few semesters. But Burak was determined. His persistence won faculty approval, and now, four semesters later, PeaceMaker is nearly ready for commercial launch. Burak’s goal, he says, is to change the image of the video game industry.

“If you look at the video game industry today, there are so many games about violence, war, and destruction. We say a simple thing: There is certainly a place for one little game about peace.”

In fact, it’s not just one little game. PeaceMaker is on the cutting edge of a new trend in the video game industry: games that try to heighten users’ awareness of real-world social and political issues. According to Henry Jenkins, a leading scholar of popular culture who heads the Media Lab at MIT, these “serious games” or “social impact games” are “games which represent some aspect of the real world” with an eye toward changing the world for the better.

Some games that are classified as “serious games” have a purely educational mission, linked to K-12 curricula. One example is Revolution, an online game that Jenkins himself developed, where students play as characters in a realistically depicted American colonial settlement of the late 1700s. Then there are the military training “serious games,” like the U.S. Army’s own America’s Army, which simulate the experience of being a soldier.

But other serious games have a more activist bend. The best example is Food Force, a game created by the United Nations in which players distribute food to starving peoples around the world. There’s also A Force So Powerful, which teaches the techniques of non-violent organizing and activism. According to Marc Prensky, an expert on educational video games and author of the new book Don’t Bother Me Mom—I’m Learning!, these games are designed to entice users into learning about topics they might otherwise ignore—like social activism or global food distribution—using the carrot of the video game experience.

Asi Burak and his PeaceMaker co-director, Eric Brown, are banking their careers on the future of serious games. Since graduating from Carnegie Mellon in May, they have created a company called ImpactGames and they are looking for investors who share not only their desire for profit but also for effecting positive change through technology. They want to continue developing and improving PeaceMaker for eventual sale to high school and college classrooms.

Burak and Brown have reason to be optimistic. PeaceMaker has already proven to be an effective educational tool in the classroom of Carnegie Mellon Visiting Associate History Professor Laurie Eisenberg. Eisenberg, who is also a faculty advisor for PeaceMaker, has used the game in two of her recent courses on Middle East history. She required her students to play PeaceMaker from both the Israeli and Palestinian sides as part of their homework; afterwards, she asked them to write a short paper reflecting on their experience.

To play the game, players can choose to be either the Israeli prime minister or the Palestinian president. These are anonymous characters (though both are male), since the specific leaders of each side in the “real world” are subject to change. The player’s score on the Israeli side is broken into two parts—Israeli public opinion and Palestinian public opinion—and the scores fluctuate depending on how well he handles challenges like suicide bombings, political negotiations, and the demands of various social groups. If the player chooses to be the Palestinian president, the objective is to match a positive Palestinian public opinion with the opinion of the international community. When the game starts, the player is treated to the sounds of rhythmic Middle Eastern music (composed by another of PeaceMaker’s faculty advisors, Tina Blaine). The music sets the tone for the experience with its deep, urgent beat pulsing between the more ethereal tones of a haunting flute melody.

The first time I tried PeaceMaker, I played as the Israeli prime minister. I came to the game as a left-leaning activist/peacenik with experience living in the Middle East. In college, while getting my BA in Middle Eastern studies, I studied at Israel’s Hebrew University and lived with Israeli Arab women. So the first thing I tried to do when I played PeaceMaker was to give medical and educational aid to the Palestinians. My aid, however, was refused by the Palestinian president, who called my action “arrogant.” My Palestinian public opinion score was low, so I tried to release some Palestinian prisoners and give aid to Palestinians living in refugee camps. Within a few minutes, my Palestinian opinion score had increased to 12/100, but my Israeli public opinion score had dropped to -30/100. A screen popped up with a photo of Israeli Knesset members, who were calling my actions a “comedy of errors.” I found that in order to increase my ratings within Israel, I had to perform mild security actions, such as increasing checkpoints and patrolling police forces, while making speeches about the importance of peace and compromise on both sides.

After a little more than an hour, I had figured out how to “win” the game. But the overall experience of playing the game was a revelation. There were so many different constituencies to please within Israel (the Israeli Left, the Orthodox settlers, the Knesset, the Army), and it was also very difficult to win the trust of the Palestinians and the support of world leaders.

My reaction was similar to that of many students who played the game as part of Professor Eisenberg’s course on Middle East history, which included both Carnegie Mellon students in Pittsburgh and Arab-Muslim students in Doha, Qatar, who were taught via webcast.

One of Eisenberg’s American students, Marie Yetsin, is from a Jewish family that is strongly pro-Israel. After Eisenberg’s class, however, Yetsin began to realize that “Israel had also made mistakes and that the Palestinian people had some legitimate claims.” PeaceMaker, she explained, “showed why it was so difficult to make peace between the two sides.” Though she won the game several times as the Palestinian president, she was never able to win as the Israeli prime minister. “I could never get the Israeli public opinion and the Palestinian public opinion to match up. I didn’t know how to make everybody happy.”

Eisenberg found the game to be a powerful teaching tool. “My students never ‘forgot’ to do their game homework,” she said.

“Moreover, they continually referenced PeaceMaker in subsequent classes.” For Eisenberg this was unusual: “Students rarely refer to their assigned readings; they don’t say ‘remember that textbook we had in the beginning of the semester?’ But with PeaceMaker they would say ‘It is just like in the game when…’ Pedagogically, it’s really exciting.”

Another of Eisenberg’s students, Max Martinelli, also came to Eisenberg’s class with a pro-Israel point of view. Today he says he has a better understanding of the historical situation and the logic behind the Palestinian claims.

But Martinelli, an experienced gamer before taking Eisenberg’s class, said he did not enjoy the experience of playing PeaceMaker, especially as compared to commercial games. At the same time, however, he found his PeaceMaker homework to be “more enjoyable than writing a paper about a lecture or an essay.”

“It wasn’t a game I would play just for fun, but as an educational experience, it stimulated more of the senses.”

Serious game expert Marc Prensky also offers some criticisms of PeaceMaker. He calls it “good and interesting” but perhaps “not as revolutionary as the authors claim.” He places PeaceMaker in the context of other gaming traditions, like the on-paper scenario games played by diplomats to prepare for difficult negotiations, and Prensky’s own peace game, designed for the U.S. Military, Stability Operations: Winning the Peace. While Prensky sees a growing market for serious games, he thinks that most of them “should be funded by universities or foundations and then distributed for free.” Prensky has been trying to promote this distribution strategy himself: He manages a Web site (www.socialimpactgames.com) where users can find a cornucopia of serious games to play at no charge. In some ways, Prensky’s philosophy of free distribution reaffirms the philanthropic goals that motivated many serious game creators in the first place.

On the other hand, Henry Jenkins of the MIT Media Lab supports the efforts of for-profit serious game companies. But he concedes that it will take a lot of financial investment to give serious games the high production values of best-selling violent games like Grand Theft Auto. “It’s much, much harder to get these games to a point where they look and feel like commercial games.”

With these issues in mind, PeaceMaker creators Burak and Brown have been trying to elevate their game far beyond a basic lesson on the Middle East, and they’re not afraid of negative feedback. For the last year they have been constantly testing the game across demographics and carefully recording user responses. Their goal is to make the game more exciting to play as well as politically balanced. When they first showed it to Professor Eisenberg, for example, she noticed something that they had not considered.

“They had overlooked releasing Palestinian prisoners as a possible action for the Israeli prime minister,” she said, “even though it’s one of the primary Palestinian demands.”

Eisenberg also insisted that they get some Palestinian advisors; subsequently Burak and his team found Hanadie Yousef, a charismatic and outspoken young Palestinian woman who studies chemistry at Carnegie Mellon.

Last fall Burak and Brown debriefed Eisenberg’s American students and then traveled to Qatar to interview the Muslim students who had taken Eisenberg’s class via webcast. The positive response they received from Qatari students surprised Eric Brown.

“We were expecting the students to tell us that our game was biased, inaccurate, or boring,” he said. “But they didn’t. They told us that when they played the game as the Israeli prime minister they gained new sympathy for the Israeli point of view.”

Reactions like these encourage Burak and Brown to think that there could indeed be a future in selling virtual peace. When they recently tested the game with a group of Pittsburgh Catholic high school students, they had a hard time prying the students away from the game in order to get them to talk about their experiences.

But regardless of PeaceMaker’s long-term commercial prospects, Burak and Brown are also proud of the impact they’ve made on people who have played the game already. Their test groups have shown that video games in the classroom may help students become more engaged in their lessons, rather than being passive learners.

For example, among the written evaluations offered by students in Eisenberg’s course at Carnegie Mellon, one American student explained how he was moved by the experience.

“The game really did explain the difficulties of the peace process far better than assigned readings and discussions,” he wrote, “because the player becomes an active participant.”

Comments