Over the past two decades, the number of published scientific studies of gratitude has exploded, said University of California, Davis, psychologist Robert Emmons at the start of the Greater Good Gratitude Summit on June 7, 2014. Today, he said, we know from this research that saying “thank you” increases happiness, improves relationships, and even lowers your blood pressure and strengthens your heart.

The Greater Good Science Center has been fueling the growth of that knowledge through its Expanding the Science and Practice of Gratitude program, which for three years has underwritten the work of 29 scientists and graduate students—many of whom shared their cutting-edge insights with the audience of more than 600 people who attended the Gratitude Summit in-person and on-line.

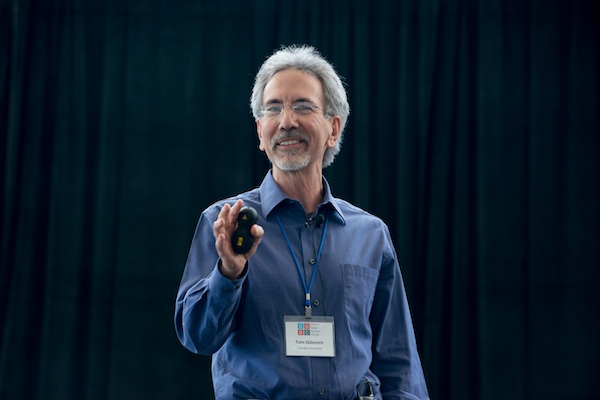

Robert Emmons opens the Greater Good Gratitude Summit.

Robert Emmons opens the Greater Good Gratitude Summit.Funded by the John Templeton Foundation and run in collaboration with UC Davis, this research is exploring topics that range from the neuroscience of gratitude to the role of gratitude in romantic relationships to how gratitude might reduce bullying.

Here are some highlights from the Greater Good Gratitude Summit, with photographs by Auey Santos.

The spiritual side of gratitude

Brother David Steindl-Rast and Jack Kornfield say “thank you” to the audience of the Gratitude Summit.

Brother David Steindl-Rast and Jack Kornfield say “thank you” to the audience of the Gratitude Summit.Long before science tried to understand why and how gratitude works, spiritual leaders fostered gratitude through teachings and ritual. Thus it seemed appropriate to start the Gratitude Summit with a conversation between Benedictine monk Brother David Steindl-Rast and world-renowned Buddhist psychologist Jack Kornfield.

Brother David posed a mystery: Why do some people with many troubles also have great joy, while others with few problems are miserable? The difference, he argued, is gratitude. “That joy that doesn’t depend on what happens,” he said, “is the joy that springs from gratefulness.”

Kornfield reflected on how gratitude is what helps us to change for the better through difficult or even terrible experiences. “We are vulnerable to one another and to the vicissitudes of life,” he said. “But what spirit we bring to that vulnerability or to the brokenness or to the difficulties . . . becomes a place also that transforms, that changes us in some profound way.”

Brother David imagined how it would change society if this attitude—gratitude in the midst of difficulty—became widespread. In our society, he said, “Whenever your heart is filled and filled and just wants to overflow with thanksgiving and joy, there comes advertising, which tells you, ‘No, no, there is a better model and your neighbor has a bigger one.’”

Gratitude, he said, is the antidote to the problems that come with consumer society—a point later echoed at the Gratitude Summit by psychologist Thomas Gilovich.

How gratitude changes our bodies

Wendy Mendes of the University of California, San Francisco, explains her research into the effects of gratitude on health and aging.

Wendy Mendes of the University of California, San Francisco, explains her research into the effects of gratitude on health and aging.In the first panel of scientists, Christina M. Karns of the University of Oregon explored the impact of gratitude on the brain. Her experiments so far have found that gratitude is linked to cognitive control and rewards systems of the brain—and that feeling gratitude compels us to give back. Wendy Mendes of the University of California, San Francisco, explained her research into what biological pathways, like the neuropeptide oxytocin or the Vagus nerve, lead from gratitude to its well-studied health benefits.

Their studies are ongoing, and they have not yet published results. But the next panelist, psychiatrist Jeff Huffman, was able to describe the daily impact of gratitude in his work at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“Every day, I get to see the powerful effects of gratitude on people in the cardiology wards and on people in our psychiatric units,” he said. He is finding that in the first few weeks after a heart attack, grateful people are more likely to take medications and regularly exercise. In work with psychiatric patients, his team also tested the effects of two gratitude exercises against six other research-based practices—and they are finding that fostering gratitude is by far the most effective way to limit suicidal thoughts.

Philip Watkins of Eastern Washington University rounded out the first panel by describing the cognitive and social benefits of gratitude. He called gratitude a kind of cognitive training that “amplifies of the good in your life.” In one study of a “three-blessing” intervention, he found that the well-being of participants kept increasing even after they were no longer counting their blessings. “Grateful recounting may train you to notice the good, make positive interpretations of good events, and reflect more positively on your past,” Watkins said.

The trouble with gratitude

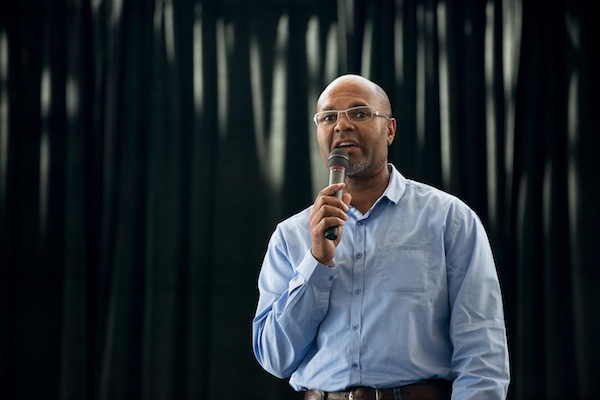

Thomas Gilovich explores the “enemies of gratitude.”

Thomas Gilovich explores the “enemies of gratitude.”The second scientific panel saw some sparks fly between participants.

It started with a bracing presentation from Cornell psychologist Thomas Gilovich about the “two enemies of gratitude”:

- The headwinds/tailwinds asymmetry. That is, our tendency to see the things that are holding us back more clearly than the good things that are pushing us forward—a concept known elsewhere as “negativity bias.” The solution, according to Gilovich, is to tell a story about overcoming headwinds, which fosters gratitude.

- The remarkable power of adaptation. This is the simple notion that we tend to get used to things, which often renders the good things invisible. The very act of expressing gratitude helps overcome adaptation, suggested Gilovich.

He also discussed studies that find experiences foster gratitude, while acquiring possessions actually seems to discourage it, in part because it’s so much easier to get used to stuff and take stuff for granted. Gilovich closed his presentation with a political argument. The American economy and culture, he said, tends to emphasize expanding consumption and acquiring possessions over having the kinds of powerful experiences that foster gratitude:

It’s governments that provide an experiential infrastructure… You can’t go out bike riding or hiking if there are no trails, you can’t have gratifying experiences at the beaches or national parks if they’re all falling apart. The experiential infrastructure is decaying, there’s no question about it, and therefore one message of this research that I hope you all take with you is to remember it at the ballot box. We do need to invest in our experiential infrastructure.

After Gilovich, social psychologist Amie Gordon and University of Stirling researcher Alex Wood talked about times when gratitude can become problematic, often because the person expressing gratitude has less personal or social power than the person who receives it, as in an abusive relationship—or because gratitude gets taken to unhealthy extremes.

“There is no such thing that is good for everyone at all times in all settings,” said Wood.

In an impromptu response, Robert Emmons disagreed with all three panelists. “I heard a lot of things that are interesting and provocative,” he said, “but also I heard a lot of things that I disagree with, that I think are flat-out incorrect.”

For example, can you be too grateful, as Gordon suggested? Emmons argued that the evidence to date on positive emotions says you cannot. He also argued that the strongest barrier to gratitude is not, for example, a consumer society, as Gilovich suggested, but instead “the self, is me.” When gratitude becomes a “self-development project,” its benefits decline—because it becomes about ourselves instead of other people.

Who is right? Video from the Gratitude Summit will soon be available, and you’ll be able to decide for yourself who was most persuasive.

Gratitude in the real world

Chris Murchison, vice-president of staff development and culture at HopeLab, talks about fostering gratitude on the job.

Chris Murchison, vice-president of staff development and culture at HopeLab, talks about fostering gratitude on the job.The Gratitude Summit also featured speakers who talked about applying gratitude to success in daily domains like the family and the workplace.

Teri McKeever, coach of the 2012 U.S. Olympic women’s swimming team, talked about fostering gratitude in athletics. Since gratitude strengthens relationships, in part by revealing interdependency, it makes sense that fostering “thank you” would help build team spirit.

“If you take a moment before practice to think about what you’re grateful for, and hear your teammates also express their gratitude, I guarantee those practices are always more productive and more cohesive,” she said.

Sara B. Algoe, Andrea Hussong, and Giacomo Bono all discussed fostering gratitude in couples and families. Based on her research, Hussong recommended that parents think about gratitude in their children as “more than showing good manners”—as a “process that begins by being aware of the gifts you receive,” in order to increase their sense of meaning.

Chris Murchison, vice-president of staff development and culture at HopeLab, a company that harnesses “the power and appeal of technology to improve human health and well-being,” talked about putting gratitude to work in his company. “I like to think about the workplace as soil, as Earth,” he said. We can add gratitude, compassion, and empathy to the soil, he argued, in order to help grow a positive work environment and to help people express “their best selves.”

And yet, pointed out Murchison, a study from the John Templeton Foundation found that people are less likely to express gratitude on the job than anywhere else. Murchison described HopeLab employees taking small steps like writing appreciative haikus for each other, and taking big steps, like ditching performance reviews for a conversation that helps the employees explore what they appreciate about their jobs and coworkers.

UC Berkeley psychologist and GGSC co-founder Dacher Keltner closed the Gratitude Summit by thanking everyone who made the day possible, from the volunteers to the funders—but especially the scientists. “It takes a lot of courage to study something that science might be skeptical of,” he said. “They’re all breaking new ground.”

More highlights from the Gratitude Summit

All photographs by Auey Santos!

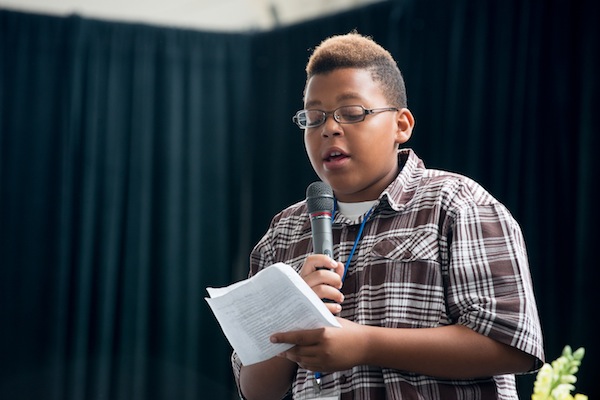

Fifth grader Maurice reads from his gratitude journal, which he’s keeping as a participant in the West Oakland tutoring program Project Boost.

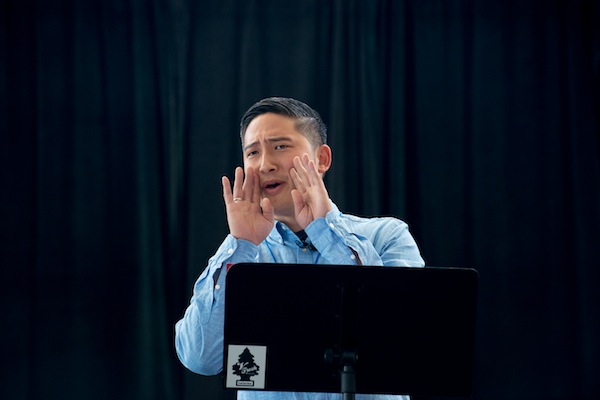

Fifth grader Maurice reads from his gratitude journal, which he’s keeping as a participant in the West Oakland tutoring program Project Boost. Renowned performance poet Dennis Kim shares his work.

Renowned performance poet Dennis Kim shares his work. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, psychologist Sara Algoe discussed how gratitude can enhance romantic relationships.

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, psychologist Sara Algoe discussed how gratitude can enhance romantic relationships. The Gratitude Summit was sold out.

The Gratitude Summit was sold out. The Gratitude Summit featured artwork by Terri Friedman and her students at the California College for the Arts.

The Gratitude Summit featured artwork by Terri Friedman and her students at the California College for the Arts. GGSC science director Emililiana Simon-Thomas and her mother share a hug during the Gratitude Summit.

GGSC science director Emililiana Simon-Thomas and her mother share a hug during the Gratitude Summit.

Comments