A decade ago, Branford High School had a bullying problem. Harassment, violence, and graffiti became so prevalent that administrators created a far-reaching anti-bullying program aimed at changing the entire climate of their suburban Connecticut school. Since then they’ve witnessed a remarkable change: levels of bullying and violence have dropped by more than 50 percent.

“When I first took over in 1990, I would be inundated with behavioral referrals,” said Vice-Principal David Maloney. “Now, I hardly get any at all.”

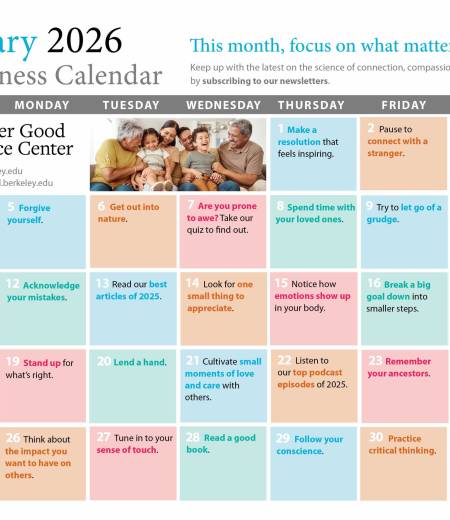

A second-grade students at PS200 in Flushing, New York, participates in the Operation Respect anti-bullying program. This year the program is being implemented in every elementary and middle school in New York City.

© Nancy Bareis

A second-grade students at PS200 in Flushing, New York, participates in the Operation Respect anti-bullying program. This year the program is being implemented in every elementary and middle school in New York City.

© Nancy Bareis

Administrators at Santana High School in Santee, California, had a similar problem. Bullying became such an issue among their students that they received a $123,000 Justice Department grant to implement an anti-bullying program in 1998. Yet three years later, the school was the scene of violence worse than anything its students had experienced before. Freshman Charles “Andy” Williams killed two classmates and wounded 13 other people with his father’s gun, a shooting rampage that began in a boys’ bathroom. Afterwards he claimed his crime was a response to the bullying he had suffered from fellow students.

The contrast between these two stories underscores a challenge faced by researchers, educators, and legislators nationwide. Over the past two decades, a wave of scientific research has repeatedly documented the harmful and lasting impact of bullying among youth. Researchers have found clear evidence that bullying, long thought to be a benign rite of passage, actually contributes to violence and mental health problems. In response, educators and researchers have developed an abundance of anti-bullying programs.

While motivated by good intentions, these programs don’t always get good results. Some have proven effective, some haven’t, and some haven’t been scientifically evaluated at all. Now educators and researchers are trying to identify and implement the best anti-bullying practices before the problem gets even worse.

Recognizing the problem

Perhaps the first question about bullying is how to define it. The Department of Justice says that bullying involves acts where there is “a real or perceived imbalance of power, with the more powerful child or group attacking those who are less powerful.” Generally, researchers break down bullying into three categories: physical (hitting, kicking, etc.), verbal (name calling, teasing, etc.), and psychological (social exclusion, extortion, coercion, and rumor spreading).

Many of these behaviors seem an inevitable part of growing up. But the studies of bullying have called that assumption into question.

Researchers have linked bullying to violence and mental health problems among victims and perpetrators. Victims often suffer from low self-esteem, reduced academic performance and, in extreme cases, commit suicide or violent acts of retribution. Several long-term studies have found that students who engage in bullying during school are more likely to be incarcerated later in life. In 2002, the American Medical Association warned that bullying is a public-health issue with long-term mental-health consequences for both bullies and their victims. A recent study by UCLA researchers Jaana Juvonen and Adrienne Nishina showed that students who witness acts of bullying experience increased anxiety and develop negative associations with school. And the Department of Education has produced this startling statistic: Each day, 60,000 students in the U.S. avoid going to school because they fear being bullied.

“It is far from being a simple playground ritual,” said Russell Skiba, a leading bullying researcher who directs the Safe and Responsive Schools project at the University of Indiana, Bloomington. “It is something that we need to take seriously.”

In the United States, the public has started to take bullying seriously, and beyond the statistics, this increased awareness can be traced largely to one event. After the shootings at Columbine High School in 1999, where the teenage gunmen were said to have targeted classmates who bullied them, the Secret Service initiated an investigation into school violence. Their report, released in 2002, found that in 37 school shootings since 1974, two-thirds of the attackers had said they felt “persecuted, bullied, threatened, attacked, or injured.”

In the wake of these findings, no fewer than 22 state legislatures have responded by passing anti-bulling legislation that requires schools to monitor and respond to bullying behavior. Congress took up its own anti-bullying bill this past year; though it didn’t pass, it is gaining support and will most likely be re-introduced next year.

Anti-bullying programs are in place all over the country. This year, one of the largest of these programs, “Operation Respect,” is being implemented in every New York City elementary and middle school. Roughly 10 percent of all school-aged children in the country are currently engaged in the “Operation Respect” curriculum.

But these programs are not all created equal. Indeed, some take a very different approach than others. As part of their anti-bullying efforts, some schools have gone so far as to adopt “zero tolerance” policies that mandate harsh penalties, including suspension or even expulsion, for any student found to have bullied another. These penalties sometimes seem disproportionate to the offense. In one case, they meant that a student was suspended for drawing a picture of a weapon.

Complicating matters further, many of the anti-bullying programs have yet to be rigorously studied; even among the programs that have been studied, the results are sometimes hard to make sense of.

Mixed results

Norway introduced the first major anti-bullying program in its schools in 1983 after three young bullying victims took their own lives. Dan Olweus, the researcher who created the program, found that his strategies generated a 50 percent reduction in bullying. Proponents of anti-bullying programs often cite this study. But when the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program was implemented in schools in South Carolina in 1995, its effectiveness rate was only 25 percent.

Psychologists Peter K. Smith, Debra Pepler, and Ken Rigby recently published a survey of 13 studies of anti-bullying prevention programs spanning 11 countries. They found a wide disparity of results across the programs: 12 of them showed at least a modest decline in some types of bullying, but seven reported increases in other kinds of bullying.

What accounts for these discrepancies? What makes some programs work while others don’t—and how can the same program work in one context but not another?

According to Olweus, one possible reason for the disparity is the degree to which school administrators, teachers, and principals are committed to the program. Other studies support this view. For example, the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, a nonprofit coalition of law-enforcement leaders, researchers, and university officials released a report suggesting that principals who are aware and actively concerned about bullying have fewer incidents in their schools.

In Smith, Pepler, and Rigby’s cross-national study, they found that the most rigorously tested programs have two things in common.

First, they emphasize the need for the school staff, especially teachers and principals, to become aware of the presence of bullying in their schools.

Almost 30 percent of students in the United States report moderate or frequent involvement in bullying, according to a 2001 study by Tonja Nansel, an investigator with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which surveyed nearly 16,000 students in grades 6-10. A more recent poll by Harris Interactive found that roughly two thirds of teenagers say they have been verbally or physically harassed in the past year.

Yet a different study found that teachers are aware of as little as four percent of the bullying that goes on in their schools.

“It is especially difficult to recognize bullying among girls,” said Phil Mulligan, an assistant principal at Bryan Middle School in St. Charles, Missouri.

The plight of bullied adolescent girls is so subtle that, according to one study, teachers are often unaware of it until the girls reach the stage of contemplating suicide.

“We need to recognize that bullying is happening in every school,” Mulligan said. “It’s like having a boil: either you can put make-up on it, or you can lance it.”

When Mulligan decided to target bullying at his school, he began by implementing a weekly survey that asked students to report on bullying they witnessed or experienced. When the first surveys started coming back, the results were shocking. They showed an average of three reports of bullying every day; previously, Bryan Middle School had record of about two incidents of bullying each week.

“There was so much going on that we didn’t know about,” said Mulligan, “because we weren’t asking.”

Whole school approach

Smith, Pepler, and Rigby’s study also identified the importance of a “whole school approach,” with coordinated action at the level of the individual student, the classroom, and the school.

Russell Skiba endorses this approach, which he contrasts with zero tolerance policies. According to Skiba, zero tolerance policies are an anti-bullying strategy that is not only ineffective but also counterproductive. He points to research showing that zero tolerance policies don’t change students’ behavior: on average, 30 to 50 percent of the students who are suspended will be repeat offenders.

“It made intuitive sense that if we remove all troublemakers from school, we will have safer schools,” he said. “But research shows that we are much better off if we seek to prevent disruption and violence rather than reacting after the fact.”

Skiba believes that zero tolerance policies don’t get at the root causes of bullying but rather punish bullies and leave them ill-equipped to deal with their social and emotional problems. The most effective way to curb bullying in schools, Skiba maintains, is to implement school-wide programs that aim to stop bullying before it even begins.

Olweus’ anti-bullying program is a model of how to implement such a “whole school approach.” The Olweus program begins with a questionnaire that asks the students to report on the bullying that occurs in their school. The results of this survey are used to generate awareness—among parents, teachers, and students—of the need for intervention strategies. Next, the program directs teachers to establish classroom rules that clearly define bullying behavior. Then each school selects from a variety of interventions that are best suited to meet its needs. These methods can include individual counseling with bullies and victims, implementing workshop-type activities at both the classroom and school level, and restructuring school areas where bullying is particularly rampant, such as playgrounds or hallways. For instance, after some schools identify “hot spots” for bullying, they have teachers or administrators monitor these locations. One school in England went so far as to build a school with no hallways and with a bathroom attached to every classroom.

Branford High School’s “whole school approach” meant creating an AdvisoryProgram where, once a week, the students meet in groups of 12-14 with an adult advisor. During a half-hour period, students and their advisor have free and open discussions about career opportunities, school policies, community service experiences, and individual progress reports. This program has been in place for seven years, and Vice Principal David Maloney said the relationships it has cultivated between students and “caring adults” have provided the foundation for a culture of trust and respect at the school.

This doesn’t mean that there’s no violence or bullying at Branford, but the school has tried to ensure that students who get into trouble don’t become repeat offenders. Before a suspended student can return to school, they are required to meet with a member of the school’s counseling staff to discuss problems like bullying and teasing. This extra step, said Maloney, has worked to significantly reduce the recurrence of behavioral problems.

In the “whole school” model, the most effective anti-bullying programs are tailor-made to the schools they serve. When Russell Skiba implemented anti-bullying programs at five separate schools in Indiana, each school was given the freedom to shape the program to address its specific needs.

For example, staff at Owen Valley High School identified a major problem particular to their school: The hallway in front of the principal’s office was often full of students who had been sent there for bad behavior. In response, the school created an Intervention Room, where teachers could send difficult students prior to the office; once there, the students meet with other teachers to discuss their problem. Often when students are sent out of the classroom for minor infractions, or even misunderstandings, they and the teachers staffing the Intervention Room will quickly and easily remedy the situation. In other cases, when there is a more significant problem, the teachers in the Intervention Room talk with the student about their behavior and recommend steps they can take to address deeper issues. Since the school launched the Intervention Room, the number of bullying incidents, and the number of students lined up outside the office, has declined considerably.

In fact, all five of the schools involved in Skiba’s study showed significant declines—40 to 60 percent—in the number of students who were suspended for both bullying and non-bullying offenses.

Skiba points out that the schools in his study saw improvements in other areas, such as attendance and academic achievement. This kind of ripple effect also took place at Branford High School after its anti-bullying program began: attendance rose from 86 percent to 97 percent, and the results of all measures of academic performance—standardized test scores, percentage of students on honor roll, the number of students pursuing higher education—went up.

“We’re ecstatic. We’re thrilled to see these results,” said David Maloney. “It took a few years to get going, but we’ve really seen some dramatic improvements.”

But Skiba cautions that not every school can be a Branford. He stresses that even the most well-designed programs need to be implemented carefully and monitored vigorously. Without that level of commitment, school districts stand to invest a lot of money and energy in programs that do them little good.

“No matter what program is put in place, schools need to be paying attention to the results,” said Skiba, “and not just blithely assuming that they’re getting the intended results.”

Comments

Wow, thanks for this article. I love the idea of a

“whole school approach” rather than a “zero

tolerance” policy. As a youth motivational speaker, I

often speak at schools that have issues with bullying.

It’s much more effective to prevent a problem from

occurring than to treat its symptoms. I also like to put

the responsibility for changing the campus climate

back into the students’ hands, primarily through

student leadership activities and youth-directed

campaigns. Overall, great article, well done.

Scott Backovich | 6:07 pm, January 5, 2013 | Link