What can Susan Sarandon teach us about giving thanks?

Earlier this summer, I joined a team that was creating a one-hour radio documentary on the science of gratitude, produced by Ben Manilla Productions and the Greater Good Science Center for Public Radio International. The documentary is done, and is hosted by none other than Ms. Sarandon. (Check PRI’s program locator for details on when it will air on your public radio station.)

The GGSC co-produced the new radio special The Science of Gratitude, hosted by Academy Award-winner Susan Sarandon. Check Public Radio International’s program guide to learn when it will air on your public radio station.

The GGSC co-produced the new radio special The Science of Gratitude, hosted by Academy Award-winner Susan Sarandon. Check Public Radio International’s program guide to learn when it will air on your public radio station.

In The Science of Gratitude, we report on studies suggesting how being grateful is good for your health, how it can strengthen your romantic relationships, why it’s important to the workplace, and much more.

I approached all of this research as a somewhat skeptical journalist. But I also examined it as the mother of a toddler. By the time we completed the project, the reporter in me came away with a newfound intellectual appreciation for gratitude; the parent in me came away with a new mission for my son.

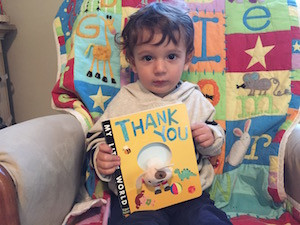

I got the gratitude bug. In fact, I even bought my toddler a little puppet book, called Thank You, all about a puppy who keeps saying “thank you” at his birthday party.

What motivated me to buy a children’s book about gratitude? The answer lies in all the research I uncovered looking at the positive effects of gratitude on children—benefits that serve them well at different stages of their development. It convinced me to raise a grateful child. Or at least do my best to raise one.

Here are the three key lessons I took away from my reporting on the science of gratitude, as a journalist and as a mother.

Grateful kids are more kind

When we feel grateful for a gift, research suggests, we’re more likely to do nice things for other people—not only for the people who’ve done nice things for us, but even for strangers.

“Gratitude is something unique because it gets you beyond the sense of indebtedness and it inspires you to pay forward benefits to someone else,” says Peter Blake, a researcher at Boston University.

Blake and Yarrow Dunham of Yale University wanted to see if—and at what age—this held true for young kids as well. They recently conducted a study measuring how gratitude might make children more willing to share. I visited them in Boston to see their research in action.

Matilda thinks about how many Starburst she's willing to part with in a study from Boston and Yale Universities exploring how gratitude affects children's sharing.

© Shuka Kalantari

Matilda thinks about how many Starburst she's willing to part with in a study from Boston and Yale Universities exploring how gratitude affects children's sharing.

© Shuka Kalantari

In their study, which has yet to be published, Blake and Dunham’s team gave a gift—a stuffed animal—to a child between the ages of four and eight. Half of those kids were told that the gift was from a specific person (another little boy or girl); the other half were told the gift was from a faceless entity (the lab at Boston University). Then they were given a bunch of Starburst candies and had the chance to share those candies with a different (anonymous) kid, though not the kid who gave them the gift.

The researchers assumed that the gift from the little boy or girl was going to induce more gratitude because it’s easier to feel gratitude toward a specific individual than a faceless lab. And sure enough, when the kids got their gift from another real person—and thus were more likely to feel gratitude—they were more inclined to pay forward the generosity: They gave away more of their Starburst to an anonymous child who had nothing to do with the original gift. Gratitude, it seems, might create ripples of kindness among kids.

But these boosts in generosity only began to appear once children turned six or seven years old. Blake says the younger kids generally kept more candy for themselves, no matter who gave them a gift.

So I’ve got a few years to practice with my two-year-old son. He doesn’t say “thank you” yet—the only word he currently says is, “Nah!” (the Farsi word for, “No!”)—but, according to Blake and Dunham’s research, I should still have hope.

Grateful teens are happier and get better grades

What really sold me on gratitude wasn’t just a vision of my kid sharing all his stuff. Looking a few years further down the road, I was impressed to find that grateful teenagers are less likely to be depressed or envious of others, and more likely to have higher GPAs and be satisfied with life. Translation: Less teenage angst, more chances that your kid will be successful enough to help pay for your retirement one day. (I’m a journalist working in the nonprofit sector, so I’m banking on the latter.)

Researching the science of gratitude and how it affects children has inspired Shuka Kalantari to start teaching her son to say "thank you" (even though he can't talk yet).

© Shuka Kalantari

Researching the science of gratitude and how it affects children has inspired Shuka Kalantari to start teaching her son to say "thank you" (even though he can't talk yet).

© Shuka Kalantari

On the flip side, a 2011 study led by Jeffrey Froh, co-author of the book Making Grateful Kids, found that materialistic teens tend to be more depressed and get lower GPAs. Froh says materialism is a value system, and kind of a crappy one.

“It’s a focus on extrinsic goals—things related to wealth, fame, image, and status,” he says. “And even if we’re successful in achieving those pursuits, the bottom line is it does not fulfill our basic psychological needs. . . . And when we don’t fulfill those needs, we end up feeling very depressed.”

One way to raise a more grateful, and less materialistic, kid is by making smart purchases. Froh says this holiday season, or on their next birthday, consider buying your kid an experience instead of a material thing. A trip to the zoo will live on in their memory; the latest popular (and thus highly over-priced) toy or pair of shoes won’t leave the same kind of lasting impression.

People who spend money on experiences instead of material objects also have stronger social interactions, according to research from Cornell University. “That’s important, because a big determinant of happiness and well-being is how socially connected we are,” says Tom Gilovich, a co-author of the Cornell study. “Being disconnected from other people is a risk factor for unhappiness and depression.”

Gilovich says humans are the sum total of their experiences, not their things. “If you ask people to tell a narrative of their life, they’re much, much more likely to mention important experiences that they’ve pursued or important experiential purchases they’ve made, and much less likely to talk about their material possessions,” he says. “And because your sense of self is more connected to your experiences, you’re just much more likely to feel grateful for them.”

Grateful kids become stewards of the environment

Even if I succeed in raising a grateful kid, the pessimist in me worries he’s not going to have too much to to be grateful for in 30 years. Diminishing funding for our National Parks and that whole climate change thing paint a pretty bleak picture of our environmental future.

But research suggests that instilling gratitude in our children might help guard against some of these environmental catastrophes. Ezra Markowitz, an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, led a study suggesting that people who are grateful to past generations of environmental stewards are more likely to do good for the environment, because gratitude enhances their sense of responsibility toward future generations.

“People who feel the most grateful toward past generations are the same ones who are most willing to put their own money on the table to support policies in order to protect parks,” says Markowitz. He says one way to build this kind of gratitude is by sharing the stories of environmental heroes who came before us—people like John Muir, Rachel Carson, and David Brower, who worked to preserve our parks and environment.

The GGSC's coverage of gratitude is sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation as part of our Expanding Gratitude project.

The GGSC's coverage of gratitude is sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation as part of our Expanding Gratitude project.

It’s really easy to get caught up in the anxieties of your kid’s development at any age. My child is almost two, and sometimes I convince myself that I’ve already irrevocably damaged his sweet little malleable mind in some way.

But I do my best. We all do our best. And now, in addition to doing my best, I say “thank you” to my toddler when he’s being a good boy. I thank my husband for washing the dishes after dinner. Knowing about the science of gratitude even compelled me to buy my six-year-old nephew a trip to the skating rink as a birthday present instead of the new Legos he wanted.

We’re going to the rink next month. He’s excited, and so am I. It will be an experience that we’ll both remember, and a memory that I will most definitely be grateful for.

The Science of Gratitude is a one-hour radio special co-produced by Ben Manilla Productions and the Greater Good Science Center, in association with UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism. It is being distributed by Public Radio International and is funded by the John Templeton Foundation. Check PRI’s program guide to learn when The Science of Gratitude will be airing on your public radio station.

Comments