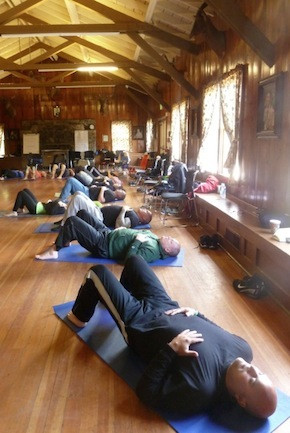

Twenty police officers dressed in sweats and T-shirts lunge on bent knees, arms stretched toward the ceiling. Some are visibly straining as the teacher instructs them to notice their discomfort and to keep breathing. These men and women in El Cerrito, California, are learning new skills, but not ones we typically associate with policing. Instead, they are learning mindfulness—moment-to-moment, nonjudgmental awareness of one’s thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

Dave Hartlung and colleagues in the El Cerrito police department learning to cultivate moment-to-moment awareness of their feelings and surroundings.

© Jill Suttie

Dave Hartlung and colleagues in the El Cerrito police department learning to cultivate moment-to-moment awareness of their feelings and surroundings.

© Jill Suttie

Lieutenant Dave Hartung is one of the officers. He’s nearing retirement, and is concerned about statistics he’s heard about survival rates for retired police—a post-job life expectancy of 10 years on average, he says. He talks about his son in Special Operations in the military who has practiced mindfulness for seven years.

“I’ve always been amazed that, even with his job and the things he’s been exposed to, how super healthy he is,” says Hartung. “I’ve decided I’ve got to learn this stuff.”

Two men are leading the training: Oregon police officer Richard Goerling and Brian Shiers, a mindfulness facilitator from UCLA’s Mindful Awareness Research Center. They combine mindful awareness practices—like mindful breathing and body scanning—with information about the science behind those techniques, making a case for their use in policing.

For an audience like police officers—where tough-mindedness is often prized—the science is critical to winning buy-in. “There’s been nothing presented to me that I’m not behind; no, they’ve been able to back everything up with science,” says Hartung. “So for me, this isn’t guessing; it’s the real thing.”

From shift work to disturbing crime scenes to emotional, angry victims and perpetrators, police face a number of potential daily stressors. It’s no wonder that many lose sleep or suffer from depression and other mental disorders. They are frequently cited as one of the professions with the highest suicide rates on the job.

Not knowing how to handle difficult emotions can take a toll on performance, too, says Goerling. A stressed-out police officer will be more likely to resort to intimidation or aggression when confronted with ambiguous situations, which can lead to inappropriate or even violent actions. Misreading a potentially volatile situation could mean putting oneself in danger—or shooting at an unarmed suspect or bystander.

That’s why Sylvia Moir, as El Cerrito’s chief of police, organized the workshop for her officers. (She is now the chief of the Tempe, Arizona police department.) “We as a profession cannot be tactically sound, operationally savvy, guard people, and put our life on the line for people we may not ever meet if we can’t see or handle the tragedy and heartache that’s part of our every day job,” she says.

Goerling, Moir, and others in the police force are at the forefront of a movement to provide support for officers, while making them more effective protectors of the community. By drawing upon research in social and psychological science, they are recognizing ways to help police officers develop the skills they need to de-escalate volatile situations, improve community relations, and better handle the demands of their jobs.

Mindfulness is an essential part of that training.

Why mindfulness?

Living in the moment might seem like a strange thing to teach police officers. But mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) has been the subject of hundreds of studies, showing that it helps decrease stress, pain, anxiety, and depression in medical patients and in other groups.

More recently, studies have found that mindfulness on the job can help workers to reduce stress, improve communications with the populations served, increase worker safety, and better work performance.

Goerling is capitalizing on this research to help police officers and other first responders with their performance. He believes that mindfulness training holds the key to many of the goals we as a community have for police—that they learn to treat others with respect and caring, and use restraint when necessary in carrying out their duties.

“Mindfulness opens up the space in which we make decisions—we’re not so linearly focused or so stressed because we are under threat,” he says. “We may still be under threat, but because I’m regulating my stress response and my emotions—anger, fear, and ego, which is a huge problem in our culture—I’m more aware of my options.”

In a pilot study conducted by Goerling and Michael Christopher of Pacific University, officers who learned mindfulness skills reported “significant improvement in self-reported mindfulness, resilience, police and perceived stress, burnout, emotional intelligence, difficulties with emotion regulation, mental health, physical health, anger, fatigue, and sleep disturbance.” This echoes some of the research from an earlier study, which found that police officers who went through mindfulness training experienced less depression in their first year of service.

Additional studies support the use of mindfulness in populations with similar stressors to police, such as those in the military. They’ve shown that mindfulness training in military personnel (like Hartung’s son) had positive impacts on working memory and cognitive resilience—the ability to use attention effectively to solve problems when you are under stress. Other studies have found that the training can decrease hostility, improve attention, and increase ethical decision-making.

Moir, too, is convinced of the benefits of mindfulness.

“The science is validating that mindfulness has the potential to increase fair and impartial policing, because we are open to recognizing our responses to a stimulus, to an event, to a person,” she says. “I really think this is going to change the way we show up for our communities. “

Still, she admits that some of her colleagues would have difficulty accepting the idea of emotional resiliency training.

“Some people think I’m absolutely bat-shit crazy for bringing this kind of training to policing,” she says. “They think it’s somehow emasculating; it makes them so they aren’t tough.”

But she argues that nothing could be further from the truth. Being able to confront oneself and be open to looking deeply at our human nature is much more difficult than just stuffing down our emotions, and it gets better results.

Self-compassion for police

Goerling believes that police need this kind of training in emotional health, because they too often get the wrong message about their job and the way emotions play a role in it. Instead of understanding the impacts of stress, anger, or fear, they try to tamp down those emotions or ignore them, which keeps them from understanding the effect of emotion on performance.

“It’s classic compartmentalizing, saying, ‘I don’t let my emotions get in the way,’” says Goerling. “Yeah, right. But what happens if those emotions spike up out of the little box and get in the way, creating problems in the encounter with others?”

Another problem, says Goerling, is that stuffing down emotions can make one more jaded with time, leading to a sense of being inauthentic, emotionally cut off from other people, and depressed. Though originally he rejected the concept of training officers in self-compassion—a mindfulness practice of directing love toward oneself—he later realized how important it was for keeping officers whole, not to mention the positive interpersonal benefits.

“This whole notion of self-compassion is huge,” he says. “It doesn’t take long in this business before you pretty much dislike everyone around you, and then you begin to dislike yourself, and then you wonder why the grizzled police officer seems to have no affect and seems to be the classic asshole cop.”

“Being tough means investing in ourselves, in actually loving people and wanting to serve them, and in feeling all of our emotions—being able to say that I’m angry, I’m disgusted, I’m sad, I’m joyous,” Moir says. “What’s remarkable to me is that my officers are seeing it: Between stimulus and response there lies choice.”

Cultivating the ability to choose is a critical tool in grappling with implicit bias—kneejerk attitudes or actions that can emerge in opposition to the officer’s explicit beliefs. Goerling acknowledges bias is part of policing—as it is with all human encounters, he says—and he believes that self-awareness is the cure for bias. We will never overcome our biases if we aren’t even aware of them, he argues. Mindfulness is one way to cultivate that awareness.

Where to go from here

Mindfulness is not a silver bullet for solving all problems facing American police, particularly when it comes to strained relations with the communities the officers are supposed to serve. Goerling believes that police can learn from social scientists and others about what is most effective for making the changes police need to make, and that they need to be open to that input.

“If you look at a lot of what’s coming into policing now, a lot of that’s coming from incestuous, group thinking,” he says. “We have to link arms with others in the community to lead ourselves out of this crisis. Until we do that, we’re going to keep getting the same results.”

Goerling is currently focused on expanding his training. In the upcoming year, he’s been asked to provide mindfulness training in San Diego, Wisconsin, and Washington, DC, and the list is growing. Though he enjoys being a spokesman for mindfulness, he hopes that communities will find more local resources for training larger numbers of officers and other first responders, giving them the tools for better health and performance through mindfulness.

As for Hartung, he has more immediate plans. He hopes to take this training back with him to help the 25 officers he supervises. He hopes that by teaching his recruits better ways to handle their emotional stressors, he can help them stay with the job.

“I have a role in commanding young officers, who are going to be in this for a lot of years, and I want something in place for them,” he says. “Law enforcement is going to have to embrace this or something like this to keep their officers healthy and have them operate at the highest level.”

Comments