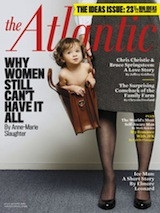

“Having it all” has been trending for two weeks, ever since The Atlantic published Anne-Marie Slaughter’s blockbuster essay, “Why Women Still Can’t Have it All.”

“It’s time to stop fooling ourselves,” writes the Princeton professor and former State Department official. “The women who have managed to be both mothers and top professionals are superhuman, rich, or self-employed.”

The GGSC's coverage of gratitude is sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation as part of our Expanding Gratitude project.

The GGSC's coverage of gratitude is sponsored by the John Templeton Foundation as part of our Expanding Gratitude project.

Feminist commentators on her essay have been quick to say that men as a group need to pick up the slack at home. “The problem isn’t that women are trying to do too much, it’s that men aren’t doing nearly enough,” writes author and activist Jessica Valenti in The Nation, citing a new Bureau of Labor Statistics report showing that working women still do the bulk of housework and childcare.

What’s missing from these critiques? Acknowledgement of how much men have evolved in just three generations.

“Men are changing very rapidly,” feminist historian Stephanie Coontz once told me. “In fact, as a historian, I have to say that they are changing, in a period of thirty years, in ways that took most women 150 years of thinking and activism.” According to every single study to date, men today do more dishes and bring more kids to school than their fathers and grandfathers ever did.

Enter the awkward concept of gratitude. It’s awkward because many women frankly resent the idea that men should be thanked for doing the work they’ve always been expected to do.

The resentment is personal and it’s political. It’s personal, because every woman who comments on these issues has had a man in her life that didn’t do his fair share. And it’s political, because the debate is fundamentally about the balance of power between men and women as groups.

“We should be grateful for anything that makes our lives easier,” says my friend Suzanne (not her real name), who is now divorced. “But at the same time, I’d grit my teeth because he was a big hero for doing a sink full of dishes.”

All partnerships have a division of labor, but Suzanne felt as though her specific labors had been imposed on her. Millions of women feel the way she did. This creates conflict, of course, but it also interferes with practicing fundamental relationship skills like gratitude. (Other skills like forgiveness and empathy are important, too, but here I’m just focusing on gratitude.)

Why should that be a problem? Because study after study shows that gratitude is essential to marital happiness. Suzanne didn’t just resent that her husband was a big hero for doing what she did every day. The bigger problem is that her daily work was thankless, and even denigrated by her husband: “If dinner wasn’t perfect,” she added, “he’d whine about it.”

In fact, research shows that men will withhold gratitude as an expression of power over women.

The place of gratitude in marriage was explored by none other than UC Berkeley sociologist Arlie Hochschild, who created a concept cited in Valenti’s article: “the second shift,” which suggests many working women face a sink full of dirty dishes when they get home. But Hochschild came up with another catchy phrase, “economy of gratitude,” which turns up much less often in feminist commentary. This theory says expressing gratitude for the labor of your spouse is more important to marital happiness than the precise division of labor. It’s not just who does the dishes; it’s also who gets thanked by whom for doing the dishes.

Researchers Jess Alberts and Angela Threthewey put Hochschild’s “economy of gratitude” theory to the test in a series of focus groups, interviews, and surveys of heterosexual and same-sex couples. They “found evidence that gratitude isn’t just a way to mitigate the negative effects of an unequal division of labor. Rather, a lack of gratitude may be connected to why that division of labor is so unequal to begin with,” as they write in their Greater Good essay, “Love, Honor, and Thank.”

So when a spouse expresses gratitude to an “under-performing” partner for picking his socks up off the floor, he’s reminded that it’s not fair that she’s usually the one who does that. “And since people who receive gifts typically feel obligated to reciprocate, this insight can lead the under-performing partner to offer ‘gifts’ of his own by contributing more to household tasks. In addition, the over-performing partner is likely to experience less resentment and frustration once her efforts are recognized and appreciated.”

Thus expressing gratitude does not necessarily perpetuate inequality, as some fear. Instead, it can help make relationships more equal.

Unfortunately, the research suggests that men are worse than women when it comes to being grateful. This makes for an emotionally lethal combination: tradition imposes housework and childcare on women, and then individual men aren’t grateful for their wives’ contributions—a habit that might have a lot to do with maintaining their own social power. As psychologist Robert Emmons notes in his Greater Good essay, “Pay it Forward”:

It has been argued that males in particular may resist experiencing and expressing gratefulness insomuch as it implies dependency and indebtedness. One fascinating study in the 1980s found that American men were less likely to regard gratitude positively than were German men, and to view it as less constructive and useful than their German counterparts. Gratitude presupposes so many judgments about debt and dependency that it is easy to see why supposedly self-reliant Americans would feel queasy about even discussing it.

While the research evidence for this idea is scant, it personally resonates with me. Averages don’t tell us much about individuals, and certainly there are men who are better at gratitude than women. But I have struggled to weave gratitude into my life, and so do many men I know.

So. If American marriages need more gratitude, that change should start with men. Other research suggests that the gratitude needs to be specific and consistent to be effective. Not just, “Thank you for everything you do every day around the house, honey” on Mother’s Day; rather, the gratitude should take the form of consistent feedback: “Thanks for making dinner tonight, this pork and kale soup recipe is delicious.” The “meta-thanks” won’t work, because it doesn’t show that you recognize the contribution as a unique and personal thing.

Does that mean women shouldn’t be grateful to men for doing the dishes?

My own answer is yes and no. Yes, individual women should express gratitude to the men in their lives for what they do, for the sake of positive reinforcement, marital sustainability, and great in-home equality (as the research by Alberts and Threthewey suggests). But no, I don’t think women should be thankful to men as a group for changing so much in recent decades. They could have and should have evolved earlier than they did, when women started taking jobs in large numbers.

This brings us to questions of power and how it shapes gratitude, which has been the subject of recent lab experiments.

One 2011 study by Yeri Cho and Nathanael J. Fast paired two participants and asked them to perform a task together—designating one the supervisor and the other the subordinate. The results were fascinating, and have useful implications for marriages. They found that gratitude from supervisors made subordinates happier, of course. But they also found that supervisors who had been challenged in any way by their subordinates were more likely to turn around and insult that person.

This is a dynamic that defines many marriages. If a wife challenges her husband’s competency at home—“Don’t you know how to sweep a floor?!”—the research suggests he’ll end up denigrating her own contributions, a vicious cycle that might be depressingly familiar to some readers.

To be fair, men aren’t the only ones who forget to be grateful. It’s commonplace for full-time caregivers—usually (but not always) women—to forget to thank breadwinning spouses—usually (but not always) men—for their efforts and sacrifices. Supporting a family is hard, especially in hard economic times, and can entail intense stress and deferred dreams. Even two-income couples, whose members are theoretically facing similar stresses, can fall into the ingratitude trap: They become too busy to see or appreciate what the other is doing.

Indeed, gratitude must go both ways to be effective. It’s the role of the spouse to serve as witness to their partner’s life. Gratitude tells the spouse that they are being seen, that their sacrifices and struggles are visible and honored.

But interpersonal power imbalances are pernicious in another way: They make us cynical about others’ motivations for expressing gratitude.

In a study published in January of this year, M. Ena Inesi and colleagues ran five experiments testing how power shapes gratitude. They found that people with power tended to believe others thanked them mainly to curry favor down the line, not out of authentic feeling. This cynicism, the researchers found, made power-holders less likely to express gratitude to people with less power. In marriages, this gratitude corruption also led to lower levels of marital commitment in the more powerful spouse.

The bottom line from these and similar experiments is clear: Having power makes you less grateful, which just exacerbates power differences and all the resentments that go along with them. But expressing gratitude can help break that vicious cycle and change the balance of power.

For me as a man, this amounts to a persuasive feminist argument. Power inequalities cut us off from genuine and necessary human feelings like gratitude—and that can push us a little further away from the possibility of happiness.

We can act against power imbalances through our votes and political activism, I believe—it’s policies like flextime and paid parental leave that will best help women advance in their careers. But we can also make a small, positive contribution in our own homes by just saying “thanks.” If we can’t “have it all,” then we can at least help each other to appreciate what we have.

Comments

I wonder how much of the potential thorniness in saying a simple “thank you” is because we really only have that simple phrase for it, so that so much of the deeper meaning (actual gratitude? Subservience? Mere politeness?) is dependent on context? It’d be interesting to see if there is a similar issue in, say, Japan, where they have so many different ways of saying “thank you” depending on the level of formality desired, whether the thing you’re thankful for has already happened or not, and so on.

This article brings up some really interesting points. Thank you for writing it!

Marjorie | 4:58 pm, July 5, 2012 | Link

Hang on….did you just say “every woman who comments on these issues has had a man in her life that didn’t do his fair share”? Are you referring to a specific article? Can you prove what you just said?

You say men have evolved more than women in the past 3 decades. Aside from your article in (ahem) MAMA magazine, do you have on hand the emperical data to which you refer?

Also (I’ll gladly try to find this study, referred to in the Boston Globe) wasn’t there some evidence that thanking someone leads them to believe they don’t need to make much more effort than they already have?

I think that among young “men”, we may see more feminism but don’t forget narcissism as well, these “men” living with their moms much longer and at age 26 they’re still called “children” under the health care laws.

Are we sure we’ve progressed that much?

Amelie | 8:55 am, July 10, 2012 | Link

From a personal standpoint only - I thank my guy, and my son, whenever they do things without my having to say ‘Hey, I’m feeling overwhelmed here, so take a look around and see what you can do so I can comment on this article.’ After coming home one day and finding the whole place straightened up and the dishes washed, I called and thanked my guy for making coming home from work less stressfull. He said that there was no need to thank him for something like that. However, I believe that when someone makes a concious decision to do something that they would probably rather not do just to be productive and thoughtful, it deserves gratitude and notice.

Men as men don’t need to evolve. Societal attitudes about duties and who ‘should’ be doing what do. If I’m ready to freak out because I’m working 40 hours a week and handling everything that needs handling, I step back and say, hey - help here. Out of respect, they do.

Maybe the discourse should change. If you’re angry about your personal situation, I fail to see why an entire gender be held responsible. Fight for equality, for respect, and for an end to stereotypes. However, if you want to change the sterotypes that surround women, I fail to see how you can do that while using male stereotypes to prove points.

Shannon | 5:09 pm, July 10, 2012 | Link

I’m still trying to work out what the purpose of this article is. While reading the title, I initially thought this may have been an interesting article exploring the value of expressing gratitude in relationships as a basis of effective communication.

However you’ve immediately launched into a half hearted defensive against comments made by feminists who were speaking on their limited experiences to support their own agendas.

Flowing on from there, the article by Hochschild which you quote was dated 1989. This is a little concerning when you go on to talk about the evolution of men and insisting they “should have evolved earlier” but use material from the 80’s to summarise the current home situation and how it should be viewed.

It would be interesting to see the statistics and data you base your opinions on and where they have been sourced from. But without this, it becomes mere speculation based on personal opinions and an unknown agenda.

I fail to see why it is a topic such as this has to be made into a gender issue, as all this appears to do is divide and imply conflict between the sexes. Surely if people come to the point of having to research if they should thank someone for doing dishes, then it’s time to assess greater issues in their life. Increasing open communication, raising self awareness and making an effort to understand other people’s expression of love would be a good place to start, before trying to segregate the issue into a gender problem.

Paul | 5:51 am, July 19, 2012 | Link

Being a man, I certainly don’t need to be thanked for

doing the dishes nor would I expect it. However, if

you would like me to do the dishes more often, it

would be a good idea. The fact this is being

discussed shows how flawed and distorted some folks

perceptions of relationships and they approaches they

take to them. The topic suggest that one party

“loses” or “gives control” by simply being pleasant and

saying “thank you.” Is it really that big of a deal?

The relationship may never fail but it certainly won’t

be what it can if people can’t get over themselves to

the point of being able to saying thanks.

Andrew | 11:18 am, July 21, 2012 | Link

Love the debate about all the issues involved in this

topic! I’m very lucky that my husband shares in

many of the household chores. We have such a

good relationship where we respect one another

and admire each other. I know that I personally

love to feel appreciated and that my work is

noticed and valued. so that when he does dishes,

I thank him. LIkewise, when I do dishes, he thanks

me. He always does the laundry every week end

and I thank him each time because I do value the

work he’s done. Also, if he comes home from work

and notices that I’ve mowed the lawn, he will thank

me and vice versa. I find that our relationship is

based on mutual respect and we honor each other’s

service to the marriage. It works wonders for me!

Lorraine Manifold | 5:47 pm, July 27, 2012 | Link

I believe that the reason why so many marriages fail is a lack of gratitude. Making sure that your spouse or significant other feels appreciated for the little things they do strengthens the relationship. I have definitely seen this in my marriage. Once I started my gratitude journel, I noticed that my husband became more verbally appreciative - thanking me for cleaning up the kitchen, or cooking dinner. In turn, I started thanking him for cutting the lawn and taking out the trash. We’ve been married for 16 years and I still feel like a honeymooner.

Lisa yan | 2:12 pm, August 10, 2012 | Link

I can’t imagine why so many people have such a hard

time saying, “thank-you.” I’m not saying I am a

better person, but I regularly thank my significant

other for doing things that would be considered

assumed gender-roles. I myself like recognition and

found that others do too. A smile and a thank you

goes a long way to encourage more of the same

behavior. Couples should be looking for small ways

such as this to lift up each other instead of working

against one another.

Andrew | 9:16 am, August 19, 2012 | Link