My 15-year-old son is like many of his high school peers. Bent on getting into a “good” college, he’s taking rigorous academic courses, studying long hours, and participating in four student organizations. He also volunteers every weekend for two hours at the Berkeley Humane Society and takes piano lessons once a week. In other words, he’s busily building his college admissions resume.

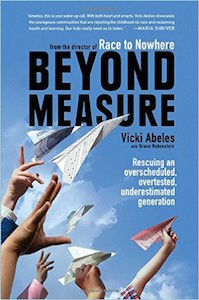

All of this probably seems normal for a college-bound teen; but therein lies the problem, writes Vicki Abeles in her new book, Beyond Measure: Rescuing an Overscheduled, Overtested, Underestimated Generation. According to Abeles, our children are so overly taxed by work and activities that they have no time in their lives to relax, to dream, to think creatively, or to just be happy; instead, the pressure to “succeed” is making them stressed out, anxious, and depressed. And, even though we may believe otherwise, their hard work is not preparing them to be the future innovators, artists, and problem-solvers we need as a society.

Abeles first brought attention to the problems with overworked and overscheduled children with her movie, Race to Nowhere. Her new book revisits her concerns with the “achievement at all costs” model of education and suggests some ways out of the madness. Providing research on the costs of overextending our kids, as well as examples of model schools that are challenging the status quo, she points the way toward improving the learning, health, and happiness of our children.

Abeles recognizes that many parents feel caught in a system that they have little control over. We are led to believe that the road to success is paved with lots of hard work, ample extracurricular activities, and a degree from a top college. This leads us to inadvertently give kids the message that achievement is the most important thing in their lives—more so than their physical or mental health.

“You want your children to learn deeply, so you push them to study. You want to give them opportunities to develop their interests—perhaps better opportunities than you had as a child,” writes Abeles. “And then, before you realize it, your life feels like it’s spun out of control.”

Scientific evidence suggests that many of the things we think contribute to a better education—lots of homework, standardized test-taking, and AP classes, for example—actually have little impact on learning and, in some cases, actually lead to poorer results. For example, Abeles cites a 2006 study in which researchers looked through fifteen years’ of studies on homework and came to the startling conclusion that doing homework is practically useless.

“Scientific research demonstrates that in many cases, homework does nothing to improve students’ academic performance, as we have always assumed it does,” writes Abeles. “In fact, those hours of assignments can hurt both health and learning.”

Another study by the National Association for College Admission Counseling led by the Harvard dean of admissions concluded by urging colleges to drop SAT and ACT scores from admission consideration because they “appear to calcify difference based on class, race/ethnicity, and parental educational attainment,” rather than measure potential for college success. And, a study by the University of Virginia and Harvard found that, once they factored in students’ academic and socioeconomic backgrounds, AP courses taken in high school had no impact on how well students performed in college.

Yet, even when the evidence is clear, nothing changes. Abeles calls out those who are complicit in maintaining the current system: colleges that compete for rankings based on how many students apply, which makes admission rates low and encourages students to distinguish themselves with higher test scores and more AP classes rather than mastery or purpose; schools that rank students, test them yearly, and have testing-based rather than learning-based curricula; and parents who fret about college admissions, pushing their children to achieve rather than learn, and enrolling their children in endless activities that rob them of free time. In doing so, she lays the blame squarely at the feet of adults, who could create a movement for change if they spoke up and took action.

For those who are inspired by her argument, Abeles provides a long list of potential actions that parents and teachers can take to start making meaningful changes in their kids’ home lives and in the schools they attend. She suggests that parents help their kids lighten their academic load, get more sleep, ignore the advertising of colleges, and pursue subjects and activities they love (not ones that look good on a resume). She also encourages communities to petition their schools to shorten the school day, change homework and testing policies, and restructure school schedules to promote better learning. Changes like these, she suggests, provide more free time to students for pursuing outside interests, connecting with friends and family, staying healthy, and getting extra help, if they need it.

The book is well-researched, Abeles’s points well taken, and the stories she provides inspiring. In particular, the words of students caught in the system are particularly poignant, and they stand in stark contrast to the lost voices of students who have committed suicide because of a misguided belief that they were failures.

Abeles’s book makes me painfully aware of how damaging the current system is—with its focus on competitiveness and achievement—and how much my children have to lose by my remaining complacent. One thing I learned from the book that I didn’t know before is that some states have opt-out policies for parents who don’t want their kids taking standardized tests—something I’m now seriously considering for my own son.

This would no doubt be good news to Abeles. Getting parents like me to take action is one of her main goals.

“We’ll be swimming upstream until we help schools undo old traditions that hurt students’ health and education and adopt new practices that tap children’s individual talents and fulfill their needs,” she writes. “We will only effect this change through a groundswell of grassroots action that begins with you.”

I, for one, am sold.

Comments