He was my age, hovering around 30, and might be dying. But what did he want with me?

A nurse pointed me to the patient’s room. I tapped on the door and entered after I heard a muffled voice say something that sounded like “come in.” It took me a moment to spot him sitting in a chair shrouded in bedsheets, a nanosecond to recoil in surprise.

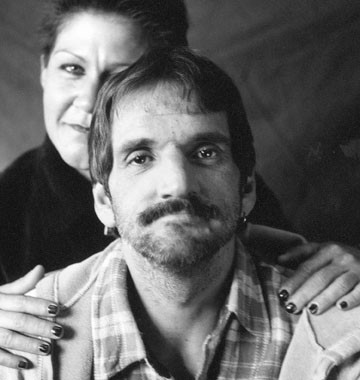

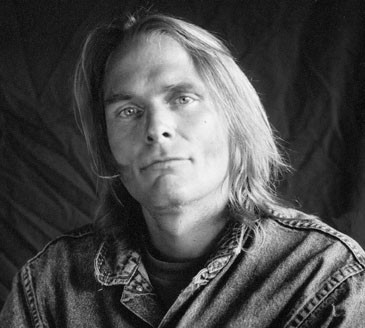

Some of the 20,000 clients and 15,000 volunteers who have connected through Shanti over the last 30 years.

© All photos by Eric Gottesman

Some of the 20,000 clients and 15,000 volunteers who have connected through Shanti over the last 30 years.

© All photos by Eric Gottesman

“Oh, excuse me,” I said. “I think I’ve made a mistake.”

I checked the room and bed number again. They were correct, but how could that be? The chart said the patient was just a year or two older than I was, but a shrunken old man looked up at me with a tube running into or out of every orifice and limb. Numbers blinked on light panels, a heartbeat spiked endlessly across a cardioscope, liquid sounds shushed through tubes. Like worried mothers, monitors hovered over every vital sign.

He said, “Hi,” then added in a voice as thin and quivery as the hand he used to motion me closer, “Come on in.”

“Jim Dees?”

“That’s me.” His laugh was hardly jolly, but warm and welcoming nevertheless. He seemed to have no muscles at all, just skin and bones and a gaunt, sweet smile. “Meet my friends,” he added, meaning the pumps and scopes surrounding his bed.

I felt like a gawker at a train wreck as I perched on the end of Jim’s bed and scanned his wasted body. Finally I took a deep breath and smiled at him as though his appearance wasn’t the least bit out of the ordinary.

“How are you doing?” I asked.

“Great,” he said.

I knew that since his diagnosis with Guillain Barré Syndrome some months before, he had been going steadily downhill. His medical team was doing everything possible, but his prognosis was uncertain. Jim was in a wait-and-see period.

I didn’t know where to begin. In all my years of training as a psychologist, I had never had a patient with such a serious, life-threatening illness, nor sat in a room where every blip on a screen or pulse of a monitor communicated urgency, a reminder that there may not be much time left. “Do you need anything?” I asked, beginning my typical ice breaking banter with a new patient. I hoped I sounded more relaxed than I felt.

“How are they treating you?”

Jim’s speaking was labored and he paused to take breaths after every few words, but he seemed to want to praise everyone who had ever emptied a wastebasket for him or fluffed pillow. The dim lighting was easier on his eyes, but Jim’s good nature brought his own light into the room.

“How are you doing?” he asked. “It’s really nice of you to come and see me. I know how busy everyone is around here.”

“Why don’t you tell me a little about yourself?” I was feeling my way, a man in the dark. What was I looking for? I unbuttoned my corduroy jacket, pulled out a fresh 3x5 card from my vest pocket and clicked my ball point pen into position.

“I’m a musician, a professional clarinetist,” he said, managing a proud smile.

“From Texas?”

“You guessed it,” he said. He told me he traveled around for his music gigs on the weekends but had a day job as a salesman to support his wife and children.

“A salesman,” I said smiling. “My father is a salesman, too.”

I was having a hard time adjusting to Jim’s physical devastation, but I found it easy to talk to him. I needed to make some sort of psychological assessment, so I started by trying to get his take on things. “Why don’t you tell me what’s happening to you?”

He took a deep breath to prepare himself for the exertion of talking. “Well, I know it’s not good. I’ve lost a lot of muscle mass already.” He lifted a rueful eyebrow. “I guess that’s no surprise. But what worries me is if this thing gets to my lungs or my heart, they’ll have to put me on machines. There’s no guarantee the machines will do the job, and if they don’t, well, it’s curtains for me.”

I took a deep breath as his meaning sank in, watched him stare at his hands. His silence communicated his understandable worry.

“Is that the worst of it?” The question sounded lame and I added, “I mean of all the

things that worry you?”

“I think what scares me the most is reaching a point where I won’t be able to talk to anyone, or speak my thoughts. Already the doctors come around, and I know they’re doing their best, but they stand around my bed and talk about my tests and my medicines and what might happen like they can’t see me lying in this bed. I’m still alive, but already they treat me like I’m dead. I mean, at this point I can still put my two cents in— barely—but suppose I get to the point where I can’t speak at all? That can happen, you know.”

I shook my head like a wide-eyed, uncomprehending student, an innocent in the laboratory of life and death. “No, I didn’t know.” My mouth was getting dry and anxiety constricted my throat. Jim’s situation was scaring me. The fear leapfrogged over my training that said, Keep your distance. Don’t get emotionally involved with the patient.

“Are you feeling depressed?” I asked.

“Depressed? No, I can’t say that I am.”

“Are you able to sleep?”

“Well, I have to say I do wake up in the night and, you know, think about things. My family and my friends get upset when they come to see me and so I try to cheer them up. But then when they leave . . . and I’m all by myself . . .”

All traces of his pleasant demeanor fell apart. He had used up what little energy it took to mount a defense against fear. Naked desperation replaced the last of his good spirits. His smile faded and he looked at me with tired, defeated eyes.

I had seen the same despair and hopelessness in the eyes of my patients before, road signs that I followed in the hope that they would lead me to the source of their anguish. Clues to recovery are often hidden in that barren terrain and my job was to uncover them. But there was no mystery here. I saw clearly the patient’s predicament. Why wouldn’t he feel desolate? Look what was happening to him. His emotional distress was tied to his illness. But since I couldn’t cure his disease, what could I do for him?

“I do the best I can,” he offered, “but I do get sort of, you know, upset sometimes, inside myself, when I think about what might happen.”

And with that simple admission, I lost my grasp on myself. Something in me floated up and away, then slipped inside his skin. I felt myself fit into the sinews of his frail body; I could imagine myself struggling to hold onto life as he was. The pounding of fear with each beat of his heart and the terror in his mind were suddenly my own fear, my own terror. There seemed to be no separation between us. I became him for a moment, felt my own muscles shrinking, my own protection in the world disappear. I tried to hide the trembling in my hands as I took notes. I had to say something so I gestured to his machines. “I guess it must be hard to deal with all this, too.”

His head fell back and he had the glazed, exhausted look of a marathon runner at the end of a race.

“And lonely,” I said on a hunch.

He lifted his head and looked straight at me. “That’s the worst part.”

We didn’t delve much deeper that first session. There was no pathology here for me to treat. He did not have classic symptoms of depression. He had no obvious relationship issues or incapacitating phobias. He was an extraordinarily aware man facing an ugly death. The psychiatry unit had nothing in its bag of tricks to cure that one. If I had left his room at the end of that first meeting, written up the interview, and presented it to my supervisor, I would have had no diagnosis to offer. The supervisor would note in his chart that Jim had been given a thorough evaluation and required no further treatment from us. Then Jim would have been left to his machines, his fate, his loneliness. It would have all been by the book and very professional.

I looked at Jim as I wrapped up the interview. There seemed little I could do for him, but after his admission of loneliness, his fear of being ignored, assumed dead even though he had a heartbeat, I knew I couldn’t abandon him. I had started down an unfamiliar path when I entered Jim’s room; my next step took me into uncharted territory. I put my pen and note card away and said, “So, do you think it might do you some good if we continue to meet like this?”

“You mean you’ll come back?”

“Sure,” I said confidently, and we set a time for the next day.

What is Shanti?

After meeting Jim Dees in 1973, I discovered a lost civilization on the cancer wards of San Francisco’s hospitals, hordes of anxious people facing a limited life span. I wanted to find a way to meet the psychological and social needs of these patients. It was obvious that I couldn’t meet this challenge alone, and many of my colleagues simply didn’t have the time or inclination to help. On a hunch, I turned to volunteers, who I trained in interpersonal and listening skills, and who could continue to provide peer support to patients even after the patients returned home. I soon realized I had a phenomenon on my hands: a cadre of volunteers who could respond to the human elements of illness and death—the isolation and loneliness that mainstream medicine does not and can not treat.

This was the beginning of the San Francisco Bay Area’s Shanti Project, the first organization in the world to train lay volunteers to provide sophisticated emotional support to seriously ill and dying people and their loved ones, something only a handful of professional therapists were doing back then. Jim Dees became our first client. Years later, after he made a miraculous recovery, Jim helped a Shanti volunteer care for another client with Guillain Barré syndrome. Though Shanti has evolved since that first hour Jim and I spent together in 1973, it has never really strayed from some of the basic lessons I learned that day.

Perhaps more than at any other time in their lives, people dealing with an illness like Jim’s need someone to talk to, someone with whom they can share their experiences and fears openly and honestly. Instead, they often face isolation from an overworked hospital staff and friends who aren’t sure how to relate to them.

Shanti equips volunteer caregivers with skills in listening, tolerance, and effective communication, and occasionally a dust mop or a sack of groceries for the bedridden. These volunteers offer companionship to men and women with AIDS, cancer, and other life challenging conditions. They understand that what they do is not psychotherapy but peer support based on compassion, honesty, consistency—skills and qualities most people possess. Shanti volunteers also learn about some of the medical and nursing challenges facing their clients and serve as patient advocates, communicating their client’s needs to health care, social service, and government agencies. But usually, volunteers’ presence is their most valuable service. They are often the only people to whom clients can truly express the chaos of their present, their anxiety about the future. This acceptance allows Shanti clients to find moments of peace, and for the volunteers, moments of grace; often for both, moments of love and transcendence.

The most helpful Shanti caregivers possess a kind of maturity that’s expressed through imagining the suffering of others— then acting compassionately on what they imagine. Examples include the volunteer who recognizes the life still being lived in the body of a wealthy cancer patient, helping her find meaning in her final days; the volunteer who gently helps an errant teenager with AIDS, ultimately prompting him to reconnect with his parents.

I’ve learned that all of us are capable of this maturity. This is vastly different from what I had earlier believed about people— that so many of us are hopelessly self-absorbed. People will challenge their precious peace of mind to serve others, not just because they are prodded to do so but mainly because such caring enhances their sense of inner peace and well-being. This caring can have health benefits as well. Recent studies have shown that certain positive psychological and social factors can boost the immune systems of people living with HIV and other life-threatening illnesses; similar research has indicated that people who provide emotional or practical support to others may live longer themselves. A program at Shanti—the Learning Immune Function Enhancement (L.I.F.E.) program—has been instrumental in spurring, collecting, and disseminating much of this research.

Shanti has no religious affiliation and preaches no dogma. Its values are grounded in the principle of compassion in action, and its almost three-decade history has proven it to be a pragmatic, results-oriented, and cost-effective model for coping with devastating community problems, while offering to its volunteers a unique opportunity to serve others and increase self-awareness. With no visible rewards for their efforts, Shanti volunteers never have the satisfaction of saving a life, easing physical pain, or stopping the spread of disease. Day after day, week after week, and year after year, they confront the enormous suffering of their clients, at times forming bonds with people they knew would die. Given that the majority of volunteers are under 40, they open themselves to the inward turmoil and difficult questions that typically accompany a head-on collision with mortality, a self-examination most people try to avoid until the later stages of life.

Shanti volunteers include scientists, video store clerks, lawyers, parents, college students, and secretaries. In age, race, education, profession, religion, ethnic background, and sexual orientation, they are a cross-section of America. They look like your co-worker, your neighbor and, probably, like you. Together, these 15,000 volunteers in San Francisco alone have provided more than 20,000 clients with over three million hours of service. Organizations in more than 600 cities worldwide in at least 12 countries have cloned Shanti’s training and service models. These groups have not been franchised by the San Francisco organization but spontaneously modeled after it, a tribute to Shanti’s methods. Shanti eventually spawned the Shanti National Training Institute, which has trained the managers of more than 1,000 organizations that draw on volunteers, including persons who worked with the teams at Ground Zero following the events of September 11. Federal and state agencies have consulted with Shanti on disaster planning—in particular, on how to organize volunteers in emergency situations. In addition to the care of people with life-threatening illnesses, Shanti’s volunteers now also offer support for the homeless, the frail elderly, teens gone astray, and marginalized women with breast cancer. Shanti and its sister groups are part of America’s unseen workforce, the volunteers who serve, support, and uplift our communities. Add the combined hours of service of all groups patterned after Shanti and you have a force for good to be reckoned with, one fueled by compassion.

In his book Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam convincingly diagnosed the disintegration of community in America. Shanti offers an antidote to this national malaise, demonstrating that in connecting to another human being through a compassionate act, we deepen the connection to ourselves; when we bond with others who serve, we strengthen our community. Volunteering is one of the best therapies in our society. Through active involvement in our own communities we break through the dominant suffering of our era—the loneliness and emptiness we feel in living life from a protective distance, the sense many people have of losing one’s life while living it.

Shanti is a Sanskrit word for inner peace, a universal goal that our troubled world seems to mock. I chose this name for the project serendipitously, but aptly, for inner peace is what Shanti’s volunteers find and provide as they reach out to others. In a time of global crisis, Shanti’s caregivers continue to show us how the extraordinary deeds of ordinary people can offer a prototype for compassionate human interactions.

Comments

Thank you for sharing this moving and inspiring article with us. There is something indescribable that transfers from one to another during those last moments. Something, that words are limited in expressing. Something that speaks of tender, loving, emotional human connections, forever touching and changing the life that is lived and the life that is lost. And, although the cycle continues we are but one and every compassionate act makes a difference.

josie aristo | 9:27 am, January 17, 2011 | Link

thank you so much for the goo dwork you all have been doin all these years.you are all the real heroes.hats off to all of you.I wish i could also work for you as im a warm person ,is there a chance?

thank you and god bless

bibs | 5:06 pm, January 17, 2011 | Link

As I began reading the opening of this article on Daily Good, I thought “that sounds like the Shanti training I went through in the early ‘90.s” So glad to ready this article and hear that the movement is still alive and thriving. I have to say it was one of the most rewarding and inspiring volunteering efforts I have ever participated in, and the training will reman with me for a very very long time. Thanks for sharing this experience.

Billie | 6:31 pm, January 17, 2011 | Link