This article is the first in a series exploring the effects that unconscious racial biases have on the criminal justice system in the United States. While this article reports on evidence of those biases, subsequent essays will propose ways to mitigate their effects.

In 2009, while chasing a man he caught breaking into his car, off-duty New York City police officer Omar Edwards was shot and killed by a fellow officer, Andrew Dunton, who saw Edwards with his gun drawn and mistook him for a criminal.

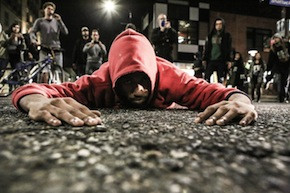

Protesters in Baltimore take to the streets following the death in police detention of 25-year-old Freddie Gray.

© Kenny Karpov, BBC.

Protesters in Baltimore take to the streets following the death in police detention of 25-year-old Freddie Gray.

© Kenny Karpov, BBC.

Edwards was African-American; Dunton is white. The incident prompted then-New York Governor David Patterson to create a task force to review all cases from the previous 30 years in which a police officer had mistakenly shot and killed another officer anywhere in the United States; it also explored hundreds of similar cases of mistaken identity that did not prove fatal, with an eye toward preventing future shootings.

Given that a disproportionate number of the victims were Black or Hispanic—12 of the 26 officers killed in the United States between 1981 and 2009, including 9 of the 10 who were off-duty—the task force members felt obligated to consider the role of race. Their conclusion? Weeding “virulent racists” out of police departments is not enough. Instead, getting to the root of the problem required “police departments to go beyond the issue of overt bias to deal with the unconscious biases that influence all people, including police officers,” they wrote. (The emphasis is theirs.)

They based that conclusion on a considerable body of scientific research. For instance, their report cites studies by psychologist Joshua Correll, who is now at the University of Colorado, in which police officers and civilians had to make split-second decisions about whether to shoot black or white suspects in a video game; some of those suspects were holding a gun, some were holding other objects, like a cell phone or wallet. Correll and his colleagues found that both police and community members were quicker to shoot blacks with guns than whites with guns, and they took longer to decide against shooting the unarmed black suspects than the unarmed white suspects. This was true regardless of whether the person pulling the trigger was white or black.

Taken together, what this and many other studies suggest is that our attitudes and behavior toward other people—particularly, but not only, people of color—are often guided by deeply ingrained judgments that operate below the conscious level. These subtle, practically automatic judgments stem from our evolutionary propensity to be wary of those who seem unfamiliar or different from us, and they’re guided by prevailing cultural stereotypes that run so deep that they can even make African Americans suspicious of people of their own race, as Correll’s work indicates. These judgments can betray prejudices that we didn’t even know we had—which makes them especially difficult to control. And in the heat of the moment, they can have tragic consequences.

The New York task force completed its report in the spring of 2010. It offered a set of recommendations for law enforcement agencies at the local, state, and federal levels, warning that, “if recent patterns hold, it is likely that another police department somewhere in the United States will find itself facing just such a tragedy this year, another will face one in 2011, and so on in the future.”

They were referring specifically to police-on-police shootings, but they made clear that their recommendations were intended to prevent the deaths of innocent civilians as well. One of those recommendations was to “accelerate the development of testing and training to measurably reduce unconscious racial bias in shoot/don’t shoot decisions.” That would include creating a federal center to spread research-based methods for reducing unconscious racial bias over the next five years.

Five years later, of course, we have not seen tremendous growth in programs to reduce unconscious racial bias. But recently—and particularly after Michael Brown was shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri—we have seen growing awareness of the science cited by the task force. In the wake of Brown’s death, research on unconscious (or “implicit”) bias was featured prominently, sometimes repeatedly, in the New York Times, the Washington Post, and many other major media outlets.

Perhaps the most profound—and surprising—mention came in a February speech by James Comey, the director of the FBI, in which he addressed the deaths of Brown and Eric Garner by saying that “much research points to the widespread existence of unconscious bias.

“Many people in our white-majority culture have unconscious racial biases and react differently to a white face than a black face,” he continued, later adding, “Those of us in law enforcement must redouble our efforts to resist bias and prejudice.”

Those kinds of efforts are now getting off the ground. Earlier this month, California attorney general Kamala Harris announced that, in the fall, the state will launch the nation’s first certified, state-wide program to train law enforcement officers in how to avoid unconscious bias. In September, former attorney general Eric Holder launched the National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice, which will use a $4.75 million grant from the Justice Department to improve relationships between minority communities and law enforcement agencies, including by targeting unconscious biases among law enforcement officers.

The challenge for these programs is not only to reduce the number of mistaken shootings but to address inequities across the criminal justice system. People of color—especially black men—are significantly more likely to be stopped and questioned by police, to be arrested, to be incarcerated, and to receive harsher sentences than whites, to an extent that far eclipses the actual number and relative severity of the crimes they commit.

Indeed, a study by Jennifer Eberhardt of Stanford University has found that black men convicted of capital crimes are more than twice as likely to be sentenced to death if they have facial features deemed to be more stereotypically “black-looking,” suggesting how subtle racial biases can sway decisions in the courtroom as well as on the street. This finding was echoed in a more recent paper co-authored by Eberhardt, published in the journal Psychological Science, that found that teachers were inclined to punish black students more severely than white students even when their classroom misbehavior was exactly the same.

Despite all of these troubling discoveries, the research also offers grounds for optimism. Neuroscience research by Susan Fiske at Princeton University, for instance, suggests that our unconscious biases are actually quite malleable. When Fiske and her colleagues showed white study participants photos of African-American faces and asked them to guess whether the people in the photos were over 21, the participants’ brain activity spiked in the amygdala, a region involved in the fear response. But when they were asked whether the people in the photos liked a certain vegetable, their amygdala activity was the same as when they saw white faces. In other words, when they were prompted to see African Americans as individuals with their own unique tastes and preferences, rather than as anonymous members of a group, their biases dissolved. A subtle social cue could make a critical difference.

And in Correll’s research, even though police officers were quicker to shoot black suspects with a gun than white suspects with a gun, the officers were less likely than civilians to pull the trigger on unarmed black suspects, and they didn’t shoot these suspects any more than they shot unarmed whites. This suggests that police officers are not any more susceptible to unconscious racial biases than the rest of the public—and, in fact, there might even be something in their training that helps guard against their biases. What’s more, a study by Florida State University researchers has found that officers who reported having positive contact with black people were less likely to shoot unarmed black suspects in a computer simulation.

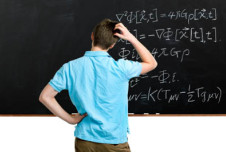

A protestor in Berkeley, California, after grand juries decided not to indict police officers in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

© Kelly Owen, Berkeleyside

A protestor in Berkeley, California, after grand juries decided not to indict police officers in the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner.

© Kelly Owen, Berkeleyside

These findings suggest that with the right experiences and training, we can mitigate the pernicious effects of unconscious racial biases. It may even be possible to not develop certain biases in the first place.

So what should be done? This question feels especially pertinent in the wake of events in Ferguson, Staten Island, North Charleston, and elsewhere. But it also takes on a special urgency now that the media, the public, and law enforcement officials are becoming more aware of the research on unconscious bias and what it means for our criminal justice system. There’s an opportunity to turn this awareness into action.

That is why Greater Good has invited a range of leading experts—psychologists, law enforcement officials, and others—to answer this question: If you could take concrete steps to mitigate the effects of implicit bias on the criminal justice system—whether in arrests, convictions, sentencing, or police shootings—what would those be? Over the next two months, we will be publishing their response essays on our site.

We realize that there are no easy solutions to this issue, no panacea. But we trust that the exceptionally knowledgeable and experienced contributors to this series—experts in the science of unconscious bias as well as in policing—will surface some provocative and practical ideas to help move this conversation forward.

While expunging all biases and prejudices from our minds is psychologically impossible, we believe it is possible to reduce or prevent the most harmful effects of those biases. Getting there will require time, openness, and great political will. But it will also require something that is fundamental to our mission: learning lessons from social science research, and applying them thoughtfully to promote the greater good.

Comments