Are kids born kind or do we need to teach them kindness? This nature versus nurture debate is an old one, but new findings published last month in the journal PLoS ONE may provide some novel insights.

The study, by Lara Aknin and her colleagues in the psychology department at the University of British Columbia, builds on the idea that if altruism is a deeply rooted part of human behavior, serving an evolutionary purpose, we’d find kind, helpful—or “prosocial”—acts intrinsically rewarding from the earliest stages of life, even when these acts come at a personal cost. In other words, performing selfless acts would make kids happy—even before they’ve been socialized to fully appreciate the cultural value placed on kindness.

© Shawn Gearhart

© Shawn Gearhart

Encouraged by the results of a preliminary study they ran, which showed that toddlers who shared a toy with someone else appeared happier than toddlers who simply played with the toy, the researchers developed a more elaborate experiment. Twenty toddlers, all a month or two shy of their second birthday, were introduced to a monkey puppet who, they were told, “liked treats.” Soon afterward, an experimenter “found” eight treats—either Teddy Grahams or Goldfish crackers—and gave them to the toddler, saying all the treats belonged to that child.

Then the experimenter performed three more steps, in varying order: found another treat and gave it to the monkey while the child watched; found another treat, gave it to the child, and asked them to give it to the monkey; or asked the child to share one of their own eight treats with the monkey. Watch the video below to see one toddler going through the experiment.

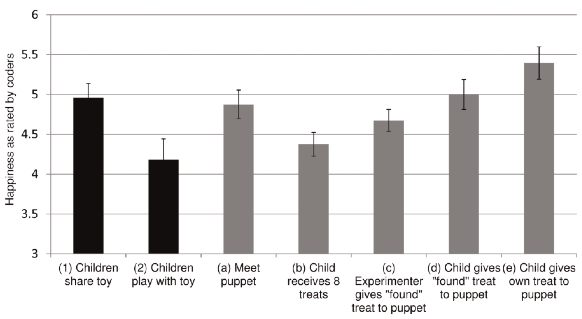

Independent observers rated the toddlers’ happiness in all three scenarios. The results show that the children appeared happier when they gave away a treat than when they received a treat, and they displayed the greatest happiness when they gave away one of their own treats; this “costly giving” even made them happier than giving away a found treat at no cost to themselves. See the graph below for a breakdown of the toddlers’ happiness levels at the different stages of the experiment.

These results suggest that children might not need much encouragement to be kind. “While the role of socialization can almost never be completely ruled out,” the authors write, “the present results support the argument that humans have evolved to find prosocial behavior rewarding.”

But couldn’t the toddlers have seemed happier simply because they sensed they were making the experimenter (and the monkey puppet) happy?

“It’s definitely plausible that children have learned that adults value kind behavior and therefore smiled more because they expected to get rewards from adults when they gave away treats,” says Aknin. But she believes she and her colleagues accounted for this by comparing the children’s happiness when they gave away one of their own treats with their happiness when they gave away a treat that didn’t belong to them.

“In both of these cases, children were engaging in identical giving behavior—giving a treat away—that should be equally praised or rewarded by adults,” she says. “They were just happiest when this treat belonged to them and therefore required personal sacrifice in giving.”

Plus, to make sure that the experimenters were not influencing the children’s reactions, the researchers had their independent observers rate the experimenter’s enthusiasm in each scenario. They found that the experimenter’s enthusiasm did not correlate with the children’s apparent happiness.

While other studies have suggested adults are happier giving to others than to themselves and that kids are motivated to help others spontaneously, this is the first study to suggest that altruism is intrinsically rewarding even to very young kids, and that it makes them happier to give than to receive.

These findings complement recent studies that have shown that giving kids rewards for their prosocial behavior may actually undermine kindness. One possible explanation for these somewhat counterintuitive findings is that, in order for children to grow up seeing themselves as kind and giving, it is important for them to feel that they do good because they want to, not because others expect them to.

Of course, this does not diminish the importance of a loving and kind environment, in which adults teach the importance of prosocial behavior, including by modelling that behavior themselves. It merely suggests that nature may have given us a happy head-start in the task of raising kind kids.

Comments

It reminds of Dorothy Law Nolte’s poem, “Children Live

What they Learn”. Could it simply be that when

children are loved, valued and cared for themselves it

gives them joy to pass it on?

Mary Margaret White-Levilain | 5:16 pm, August 3, 2012 | Link