Remember the presidential election? During the fall weeks just beforehand, many of us found ourselves compulsively checking polling websites to see if anything had changed in the last 10 minutes.

Why were we so worried? Close elections always energize the partisans. But for those of us working for an Obama win, we had the added wild card of race. This amped up our anxiety.

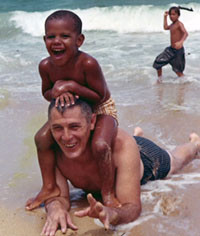

© AP Photo/Obama Presidential Campaign

© AP Photo/Obama Presidential Campaign

The anxiety was justified. For years I have researched instantaneous, nonconscious prejudice, which I described in the Summer 2008 issue of Greater Good. I’ve found, for instance, that when people see someone of a different race, their brains instantaneously go into high-alert. As a result of my research, I was especially worried that the nonblack electorate simply would not be able to shake first impressions rooted in prejudice.

I heard it in poll responses, as well as from my swing voter friends and family: “He’s too foreign”; “He makes me uncomfortable”; or “He’s a Muslim.” These efforts to define Obama as “other” were attempts to play the race card without seeming racist. But if racial prejudice is so pervasive and insidious, how could these efforts have failed? The race card should have worked, as indeed it had in so many elections. Why did prejudice falter in 2008?

The answer is that voters got used to Barack Obama. Granted, they never forgot that he’s African-American, has a funny name, and has lived in strange places like Indonesia and, er, Hawaii. But they experienced two significant things, one a series of events and the other a series of non-events—that is, things that were supposed to happen but never did.

The series of events—his public appearances, the infomercials, the debates, the endorsements from established figures—gradually made plain to voters that Obama is a three-dimensional human being, closer to a smart middle-class professional with a nice family than to a one-dimensional bogeyman. When people get to know someone from a category different from their own, research shows, they modify the way they had initially, automatically categorized that person.

In research my colleagues and I have conducted, we have found that people do not forget the category (black, female, old, poor, or whatever). But the stereotypes associated with that category can recede behind additional information that defines the other person as an individual. If that information is available, if it is unambiguous (thus difficult to distort), and if they are motivated to acquire it, the conditions are ripe for individuals to overcome their own prejudices.

In 2008, all these conditions held for undecided but open-minded voters. Balanced against all the other unambiguous and anti-stereotypic knowledge they’d acquired over the course of the two-year campaign, the potentially negative category of “African American” could recede in their minds. By Election Day, people had learned enough about Obama to complicate any initial stereotypes.

But we also witnessed a series of non-events. Obama never lost his temper. He never appeared hostile. He hardly ever even frowned, which showed remarkable self-control, given the ferocity of the attacks he faced. Indeed, people whose brains might have kicked into high-alert when they saw Obama’s face kept encountering him in the least alarming, most reassuring circumstances possible. Research, including my own, shows that, in a safe environment, when people are frequently exposed to a fear-inducing stimulus—like a face of a different race—they habituate. And in 2008, nonblack Americans did just that.

What is the broader lesson going forward? We are not a post-racial society, in that people do demonstrably notice race, even in the first few milliseconds before it reaches conscious awareness. Findings from neuroimaging studies, my own and others’, are clear: Put simply, everyone notices race.

But in other ways, we indeed are becoming a post-racial society. Most people can and do get over race when they find nothing that confirms their fears, and when it matters to them to make a careful decision.

Half a century’s research on intergroup contact points to four conditions necessary to overcoming prejudices. And in the last election, all these conditions were met: First, nonblack voters had to encounter Obama as an equal-status person (portraying him as Midwestern and middle class helped here). Second, they had to depend on him for goals that mattered (fixing the economy being one heck of an incentive). Third, they had to have non-trivial, positive experiences with Obama (his in-depth speech about race, his books, and his televised biography served as strong proxies for first-hand, positive contact with him). Finally, the relevant authorities had to endorse him (and they did, including many white conservatives).

For the future, whether in politics, the workplace, at school, or in the neighborhood, we should acknowledge that we still sometimes have knee-jerk reactions against people who seem strange, but we should also build safe situations that allow people to get used to each other. In this way, we might grow to judge others based on the content of their respective characters, instead of the color of their skin.

Comments