“Trust no one.”

That was the slogan of the TV series The X-Files, which followed two FBI agents in their quest to uncover “the truth” about a government conspiracy. Perhaps the most defining series of the 1990s, The X-Files touched a cultural nerve and captured a mood of growing distrust in America.

In the six years since the series ended, however, our trust in each other has declined even further, despite a brief rebound after September 11. The mood of cynicism and distrust captured by The X-Files in the ’90s seems just as relevant today—indeed, a new X-Files movie was released this past summer. The decline or absence of trust also figures prominently in more recent hit TV series like Mad Men, Survivor, and The Sopranos.

In fact, “trust no one” has essentially served as Americans’ motto over the last two generations. For 40 years—the years of Vietnam, Watergate, junk bonds, Monica Lewinsky, Enron, the Catholic Church sex scandals, and the Iraq war—our trust in each other has been dropping steadily, while trust in many institutions has been seriously shaken in response to scandals.

This trend is documented in a variety of national surveys. The General Social Survey, a periodic assessment of Americans’ moods and values, shows a 10-point decline from 1976 to 2006 in the number of Americans who believe other people can generally be trusted. The General Social Survey also shows declines in trust in our institutions, although these declines are often closely linked to specific events. From the 1970s to today, trust has declined in the press (24 to 11 percent), education (36 to 28 percent), banks (35 percent to 31 percent), corporations (26 to 17 percent), and even organized religion (35 to 25 percent). And Gallup’s annual Governance survey shows that trust in the government is even lower today than it was during the Watergate era, when the Nixon administration had been caught engaging in criminal acts. It’s no wonder popular culture is so preoccupied with questions of trust.

But research on trust isn’t all doom and gloom; it also offers reason for hope. A growing body of research hints that humans are hardwired to trust. Indeed, a closer examination of surveys shows that trust is resilient: Major events can stoke our trust in institutions, just as other events can inhibit it. The science of trust suggests that humans want to trust, even need to trust, but they won’t trust blindly or foolishly. They need solid evidence that their trust is warranted. Using this research as a guide, we can begin to understand why trust has been declining, and how we might rebuild it.

Why trust matters

Trust is an intrinsic part of human nature—the foundation of healthy psychological development, established in the bond between infant and caregiver, a process facilitated by the hormone oxytocin. (For more on the biological and psychological bases of trust, see Michael Kosfeld’s essay “Brain Trust,” and this dialogue between famed psychologist Paul Ekman and his daughter Eve.)

Trust is most simply defined as the expectation that other people’s future actions will safeguard our interests. It is the magic ingredient that makes social life possible. We trust others when we take a chance, yielding them some control over our money, secrets, safety, or other things we value.

People trust other people when they hire a babysitter, drive their cars, or leave their house unarmed. And we must also trust large organizations, like schools and businesses, for modern society to function. People trust institutions when they dial 911, take prescription medicines, and deposit money in the bank. Without trust, we would be paralyzed, and social life would grind to a halt.

When honored, trust promotes feelings of goodwill between individuals, which in turn benefits community. Researchers Robert Sampson, Steve Raudenbush, and Felton Earls have shown, in a study based on interviews with thousands of people across hundreds of Chicago neighborhoods, that, other things being equal, neighborhoods where residents trust one another have less violence than those where neighbors are suspicious of one another. A 2008 Pew Research Center study discovered that in nations where “trust is high, crime and corruption are low.”

Trust helps the economy. Economists Armin Falk and Michael Kosfeld have shown that, when performing tasks for others, an atmosphere of distrust reduces individuals’ motivation and accomplishments, and probably increases the cost of doing business. Other research by Stephen Knack and Philip Keefer has found that countries whose citizens trust each other experience stronger economic growth.

Trust is also essential to democracy, where people must be willing to place political power in the hands of their elected representatives and fellow citizens. Without trust, individuals would be unwilling to relinquish political power to those with opposing viewpoints, even for a short time. They would not believe that others will follow the rules and procedures of governance, or voluntarily hand over power after losing an election. If that trust declines, so does democracy.

Community, economy, democracy—once we recognize the role of trust in each of them, we can appreciate why declines in trust can be so damaging to society.

What drives distrust?

From that perspective, falling levels of trust are an ominous sign for American society. But why has trust been declining in the U.S. for so long?

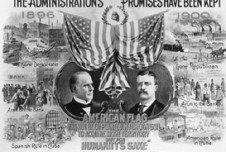

Some researchers, such as Bowling Alone author Robert Putnam, have argued that this rise of distrust reflects profound generational shifts. Americans born roughly between 1910 and 1940 were a particularly civic and trusting generation, these researchers claim, forged in the crises of the Great Depression and World War II—crises that required people to rely on one another and band together. Government dealt with these crises effectively through New Deal programs and military victory over the Axis powers, winning the confidence of its citizens.

That generation is now dying out, replaced by younger people who, according to this theory, are progressively less trusting (starting with Baby Boomers, whose slogan allegedly was, “Don’t trust anyone over 30”). In fact, a series of focus groups, conducted in 2001 by Harvard University’s GoodWork Project, revealed an “overwhelming” distrust of politicians, the political process, and the media among the teenagers they interviewed. This generational decline implies that America’s waning trust in others will not easily recover.

But why have succeeding generations become progressively less trusting? There are a number of possible explanations, none of them definitive.

For starters, trust in others depends on how much contact people have with other people—and Americans today are measurably more isolated than previous generations. They have fewer close friends, for example, and are less likely to join voluntary associations such as bird-watching groups and church choirs.

This is important, because people who belong to such associations tend to become more trusting as a consequence. Experiments, as well as experience, show that people trust people they know before they trust strangers—and so the more people you know, the more you trust. Researchers Nancy Buchan, Rachel Croson, and Robyn Dawes found that even when they created pseudo-groups by randomly giving study participants instructions on differently colored pieces of paper, the participants trusted members of their color “group” more than the others. The more memberships we have in groups—almost any group—the more trust we have in our lives.

The rise of television and electronic media as a major source of entertainment and news may exacerbate isolation, and thus play a role in the decline of trust. When the GoodWork Project ran another series of focus groups with adults in 2004, researchers “found that individuals typically blame the media for loss of trust.”

Again, the effect appears to be generational. “Most of the young people we interviewed have a default stance of distrust towards the media,” says Carrie James, research director of GoodWork. According to James, young people simply feel less tied to larger institutions and American culture—they might trust family and close friends, but “they don’t have good mental models” of how to trust more distant figures.

Of course, the most civic and trusting generation that survived the Depression and World War II grew up without TV or the Internet. Successive generations have watched more TV, in different ways, and with different program content than the older generation. Today’s young people also spend a great deal of time surfing the Internet. Both media have the effect of isolating us during leisure time and repetitively highlighting the most dangerous and corrupt aspects of our society. For better and for worse, the seemingly boundless supply and demand for voracious media coverage of scandals means that Americans are painfully aware of our shortcomings and the shortcomings of our leaders.

It’s also likely that growing economic inequality is contributing to our crisis of trust. Inequality in America declined during the mid-20th century, when our most trusting generation came of age, but the gap between rich and poor has widened dramatically since then: Since 1979, for example, the after-tax income of the richest one percent of Americans increased by 176 percent, but it only increased by about 20 percent for everyone else, with the poorest Americans earning just six percent more than they did at the end of the 1970s. As many studies and surveys reveal, most recently a 2007 report from the Pew Research Center, people feel more vulnerable when they’re at a social disadvantage, making it more risky to trust others. Thus, those of lower income and racial minorities tend to answer more often that people will “take advantage” of them.

It may also be true that America’s growing diversity hurts social trust. Many researchers have found that diverse neighborhoods and nations are less trusting than homogenous ones, though diversity is also linked to a high degree of economic vitality and cultural creativity. When Robert Putnam analyzed data from his Social Capital Community Benchmark Survey—which covered 41 communities across the United States—he found that cross-group trust was high in rural, homogeneous South Dakota and relatively low in heterogeneous urban areas like San Francisco. As America urbanizes and diversifies, trust is declining—at least in the short run.

Falling and rising

The news is not all bad. Trust in institutions hasn’t fallen in a straight line; instead, it rises and falls in response to specific events.

Consider how people answered the question about their confidence in religion between 1987 and 2006. In early 1987, 30 percent of the population said they had a “great deal” of confidence in organized religion. In 1987, however, several televangelist scandals erupted, including that of Jim Bakker. By 1988, confidence in organized religion had dropped to 21 percent. Americans’ confidence then rebounded from 1988 to 2000, eventually climbing back to pre-scandal levels. Then in 2002, as a result of the Catholic Church’s sex scandals, confidence in religious institutions dropped dramatically again, to 19 percent. Since 2002, confidence in organized religion has again rebounded—to 25 percent in 2006.

Similarly, the stock market crash of 1987 and the S&L bailout of 1989 hurt trust in banks and financial institutions. But public trust in finance gradually recovered (helped along by the boom years of the ’90s) until it received another shock, the accounting scandals of 2002. We see a similar dip in Americans’ trust in business: In 2000, 29 percent of respondents said they had a great deal of confidence in major companies. In 2002 (after the Firestone tires recall, Enron, and the wider accounting scandals), that number had dropped to 18 percent. It is too early to say what precise effect the current financial crisis will have on trust in banks and business, but, based on past patterns, we can predict that trust in these institutions will decline significantly.

So the pattern with institutions is less of general decline than of negative responses to scandals, followed by gradual recoveries. These scandals often focus public attention on a few fallible individuals—the embezzlers or child molesters. But once the shock of the scandal fades, the public returns to trusting the institution as a whole, rather than judging it by its most untrustworthy members.

Unfortunately, Americans’ trust in one another does not generally react to historical events the way their trust in institutions does. In fact, according to the General Social Survey, trust in each other has declined much more steadily and consistently than has our trust in institutions. Since there are few, if any, scandals that seem to impugn the “average person,” it takes a major event to influence America’s trust in individuals in the way that their trust in institutions is routinely influenced.

We want to believe

While it may be difficult, if not impossible, to control interpersonal trust—you cannot tell people to trust each other—we can take steps to make our institutions more trustworthy. Indeed, it may be Americans’ more resilient trust in institutions that is our best hope of restoring mutual trust. Institutions help facilitate social, political, and economic transactions of all kinds by reducing uncertainty for individuals. Experiments show that when individuals successfully engage in an exchange that involves trust, it creates more trust and positive emotions.

For instance, at the end of a series of lab experiments involving trusting exchanges, sociologist Peter Kollock reports that study participants who trusted and had that trust reciprocated sought each other out, greeted each other as old friends, and, in one case, made plans to meet for lunch the next day. Since many of our daily transactions with one another—for example, in church or at work—are mediated by larger institutions, making these institutions more trustworthy seems like a vital first step toward cultivating trust in society at large.

Research has identified steps institutions can take to promote trust and help reduce distrust. For example, by protecting minority rights (through voting protections and antidiscrimination policies), a government can facilitate trust and cooperation among individuals who might otherwise be wary of each other. Indeed, looking at 46 countries over a 10-year period, one of us (Pamela Paxton) found that more democratic countries—countries that safeguard these kinds of rights—produce more trusting citizens.

This result is echoed in other studies. For example, a team of researchers led by University of Michigan political scientist Ronald Inglehart found that countries that had embraced democracy, gender equality, multiculturalism, and tolerance for gays and lesbians saw big jumps in happiness over a 17-year period. And, according to Robert Putnam, we can build cross-group trust by promoting meaningful interaction across ethnic lines and expanding social support for new immigrants.

Part of our effort to rebuild trust should involve providing a quality education to all Americans, for study after study shows that people with more education express more trust. Working toward equality is another possible step.

Several studies have found that citizens of the most egalitarian societies are most likely to trust each other and their institutions.

There may be little that the government or other institutions can do to increase individual sociability, but individual citizens can help rebuild trust by joining community groups, connecting with neighbors, and talking to others about important issues in their lives. And if the leaders of national and local voluntary associations work to build better connections across different groups, they will help to rebuild community and a sense of trust.

Of course, we cannot blindly trust institutions, or each other. While America may want to be a trusting nation, it certainly doesn’t want to be a nation of chumps. In an age when institutions have frequently betrayed our trust—and those betrayals are amplified over and over through the media—many more people might logically and understandably see The X-Files slogan—“trust no one”—as good advice.

This is why vague, unsupported calls for increased trust in institutions like banks or the office of the President are not viable solutions to the decline in trust. Instead, Americans need to see concrete steps to improve institutional transparency and accountability, and to reduce fraud.

The exact steps vary from institution to institution, but all must be supported by an underlying commitment to honesty and reliability. Banks, for example, should implement policies to prevent the kind of deceptive lending practices that contributed to the current mortgage meltdown. Government should open records, investigate abuses of power, and hew to constitutional principles. For institutions to be able to promote interpersonal trust, Americans must be able to trust that leaders and institutions will do what they say they are going to do—keep our money safe, protect our freedoms, advance our health, and so on—even when we are disappointed by particular individuals.

In the end, it is our natural drive to trust that offers our best hope of rebuilding trust in America. That drive was summed up by the tagline for a recent summer film: “I want to believe.” Which film? The new X-Files movie. As the switch suggests, even in the worst of times, lurking under our suspicious gaze lies a need to trust in each other.

Comments